Connecting the Dots with Juan Carlos Galeano

CtD_JCGaleano_PostCover.001

Credit: FOLIO Festival

Exploring the profound connections between Amazonian cosmogonies, Indigenous knowledge, and environmental stewardship through the lens of the Colombian author, scholar, and environmental advocate.

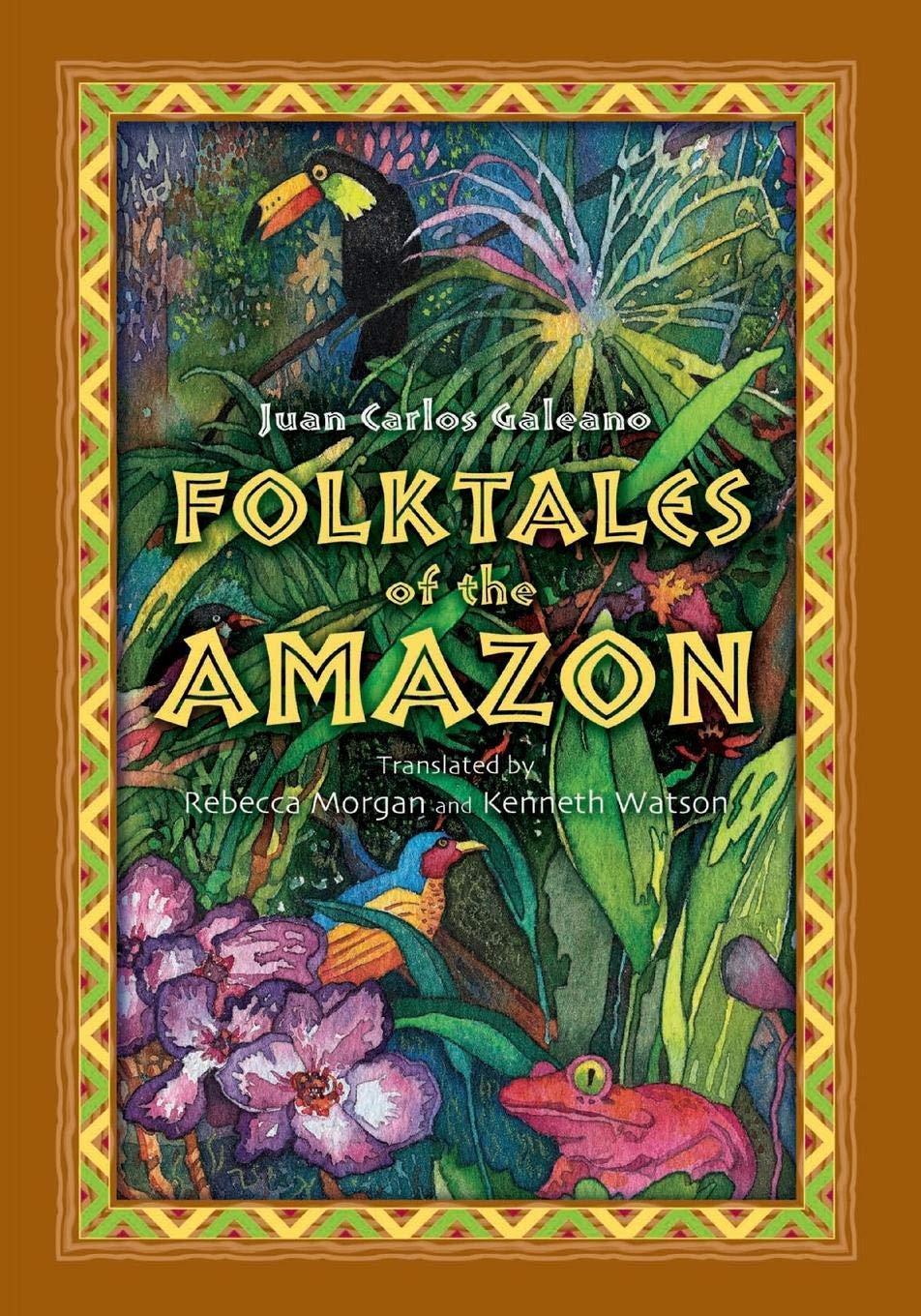

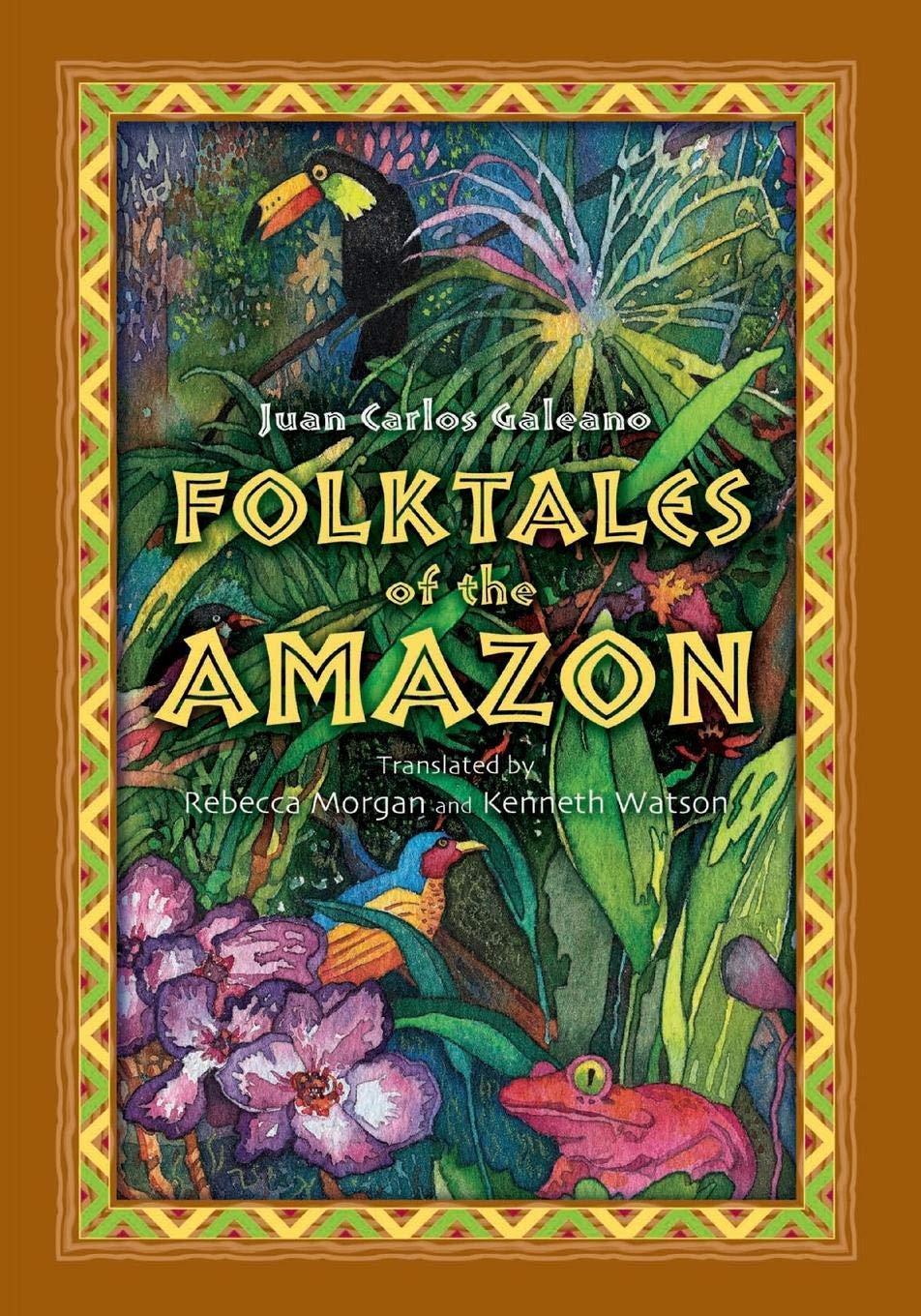

Born in the Colombian Amazon, Juan Carlos Galeano bridges poetry, academia, and environmental activism with rare authenticity. His work, including “Folktales of the Amazon” and poetry inspired by Amazonian cosmogonies, reveals the intricate relationships between Indigenous, mestizo, and Afro-descendant communities and the forests, rivers, and beings they share their lives with.

At Florida State University, Galeano teaches Latin American poetry while directing “Journey into Amazonia,” a field program in the Peruvian Amazon where students engage directly with local communities and environments rather than just studying them from afar.

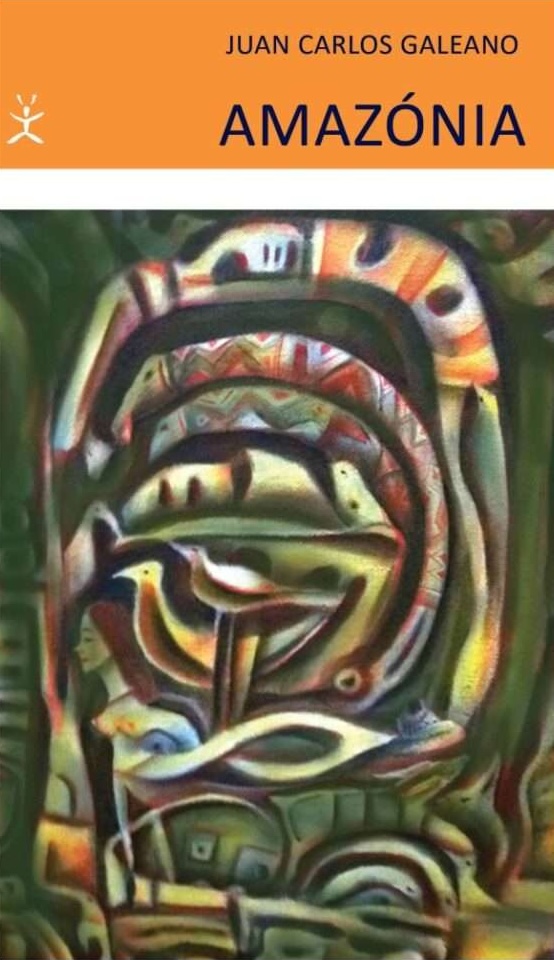

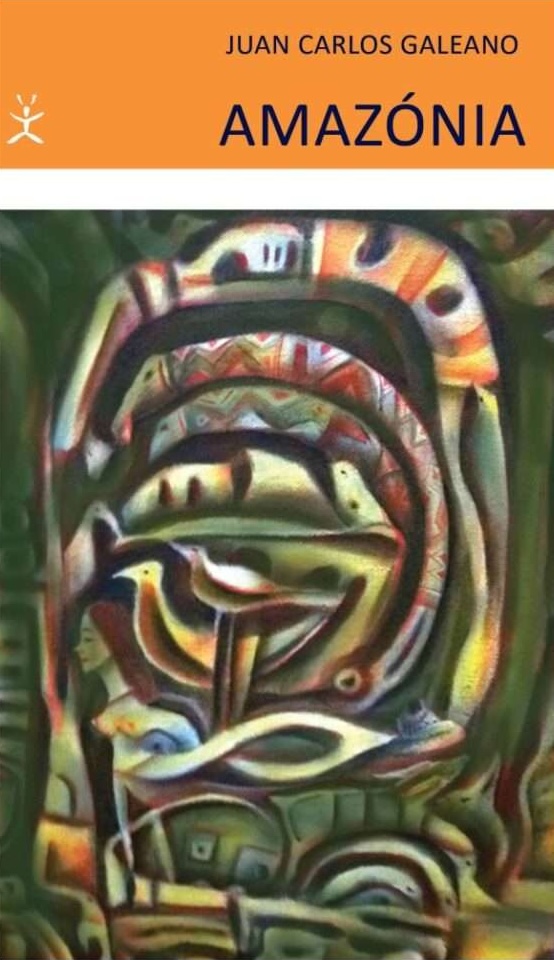

We caught up with Juan Carlos at the FOLIO Festival in Óbidos, Portugal, where his book “Amazonia” has just been translated into Portuguese, further extending the reach of these essential Amazonian perspectives.

Play the video version below (English subtitles available), or scroll down for the podcast version (dubbed in English) and for the transcript (in English).

CONNECTING THE DOTS – PODCAST

Are you a podcast fan? Make sure you subscribe to the podcast version of our Connecting the Dots series here.

ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT (TRANSLATION)

INDIGENOUS WORLDVIEWS | KINSHIP | CIVILIZATIONAL CRISIS

In fact, the great value of Indigenous worldviews for our present time is their legacy of wisdom. What sort of wisdom? Well, that wisdom of a relationship with the Earth, entirely different from what we’ve developed in Western culture.

As some Indigenous speakers mentioned earlier today, this wisdom is truly free from dichotomies and dualisms. And, fundamentally, one whereby you feel part of a family with all other beings. That means with the rivers, clouds, water, and air. As if they were our relatives, as expressed in numerous Indigenous cosmogonies. In countless myths and narratives found throughout Indigenous cultures, from each Indigenous people, in which places and other species are considered our relatives.

And as relatives, they teach us better ways to live. When we explore Indigenous narratives, and their concept of interconnected humanity, for example, we find they rest on clear principles. And this is what those principles are based on. On reciprocity. On the profound understanding that we are not alone, we are not independent beings, but rather part of a web of relationships with the whole universe. Not just our immediate surroundings, but the entire universe. I would say these entities are our fellow travelers on life’s journey.

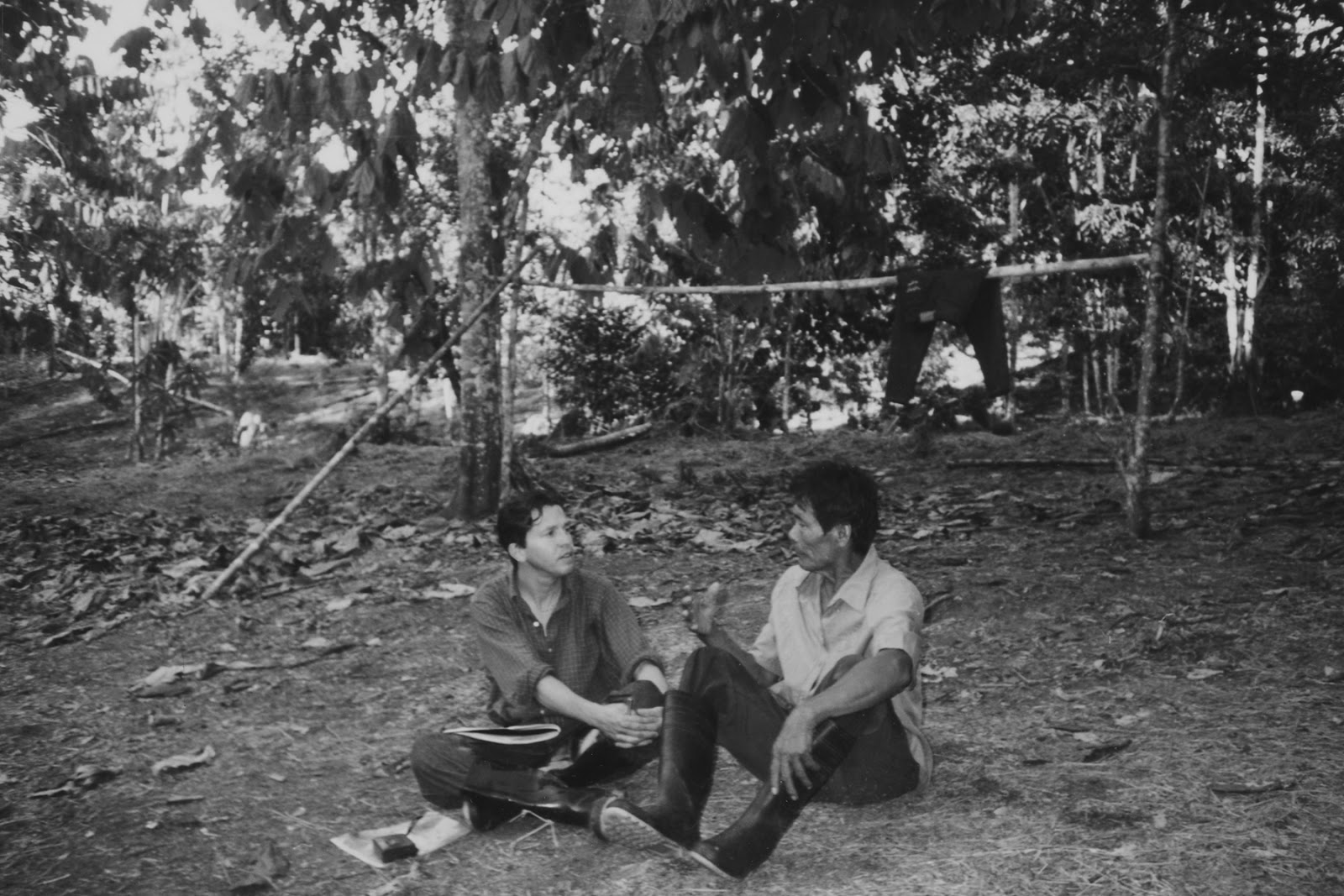

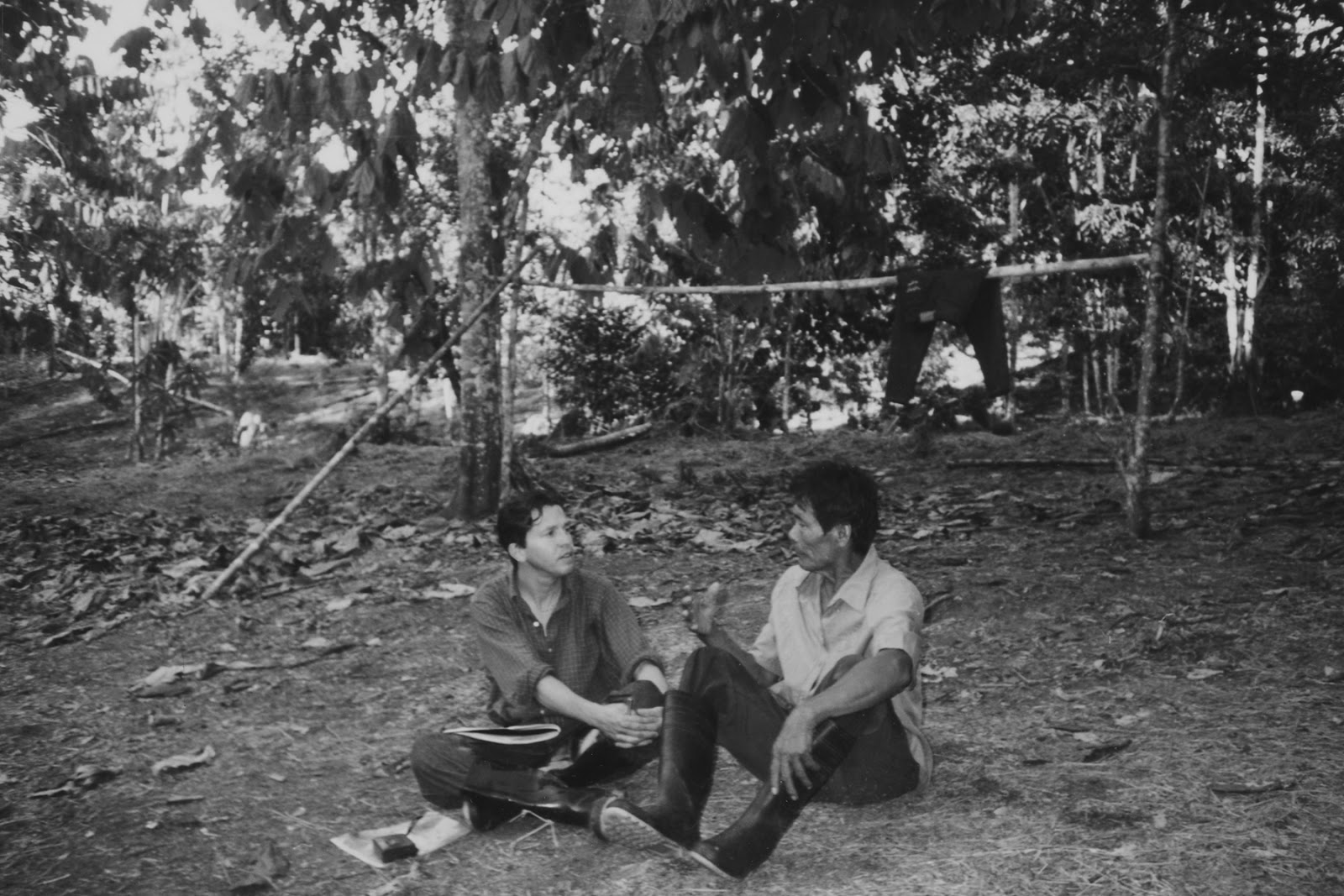

Juan Carlos Galeano y Alfredo Cumapa (Trabajo de campo escuchando historias) en el Amazonas (1998)

Credit: Personal Archive Juan Carlos Galeano

ab11e7_28fdc2b555bc4e6d9e5ea0b193f68beb~mv2.jpg

Credit: Personal Archive Juan Carlos Galeano

So, of course, if this is the legacy of Indigenous cultures, in the current moment, of modernity, it inevitably reemerges. It resurfaces because these voices were silenced by colonialism, neo-colonialism, and modernity, which have decimated not only these voices but the Earth itself.

So, Western culture, seeking narratives that enable self-critique, finds, at this critical moment, these great allies, Indigenous cultures, which preserve the wisdom necessary for the modern world. So I believe this is a fundamental principle,from which we need to begin. And starting point implies respecting and honouring these human communities, who have been marginalized and silenced. In the case of Latin America, for example, through five centuries of colonialism.

So, then, these are narratives, worldviews, that counter all the narratives that were constructed by early explorers, propagated by colonizers, and perpetuated ever since. These narratives form part of a destructive ideology. This is of vital importance in this moment of crisis. A moment of civilizational crisis, as Enrique Leff described it.

ab11e7_785c82bd0ba04facb8e328b6dd7d254a~mv2.jpg

Credit: Personal Archive Juan Carlos Galeano

ab11e7_1041c78246b64b11a13abbe0d31d05f5~mv2.jpg

Credit: Personal Archive Juan Carlos Galeano

AMAZONIAN TALES | RETELLING & REWRITING | IMAGINATION & EMPATHY

Exactly reproducing these tales would require too many pages. So why not create a mythopoetic version of a story, of an oral narrative, that can be captured in just 10 pages? And why shouldn’t we do it through a mythopoetic version? While honoring the original language of these stories. But highlighting those powerful, illuminating moments, almost like epiphanies, that are within these stories.

Besides, no story is ever retold exactly the same way. Because through our imagination, we are always transforming stories. As Italo Calvino said, “A story isn’t beautiful unless you add something new each time you tell it”. Well, as is said in Heraclitus’ aphorism, we never bathe twice in the same river. In a sense, we are the river. We also have what’s called ‘agency’.

So we are always constructing something. We are beings in constant change, like all other beings. We constantly rebuild our imagination. And what happens is that we can manipulate it. We can transcend ourselves. And when we transcend ourselves, we can imagine, we are imaginative enough to do so, how a mountain might think. How might a cloud think? How might a river think? At this point, we enter a completely different set of relationships. We’re creating an entirely different paradigm, because we recognize these entities possess their own subjectivity. Just like we do. And if they have subjectivity like us, then they too are sentient beings.

This allows us to access that other human capacity, which we call compassion, empathy. We can feel with it. Here we enter a kind of society that reconnects with those original societies, we know as Indigenous cultures. If we took time to view the world through our imagination, we might draw closer to the world and feel it more deeply.

810SFpQdXSL._CR0,0,0,130_

Ed.: Libraries Unlimited - Greenwood Publishing Group

FACILITATING EXPERIENCES | AMAZONIAN PERSPECTIVES | SITUATING KNOWLEDGE

Well, I spent many years traveling through rivers and jungles all over the Amazon, through many places, across all the countries of the Basin, and I wanted to share that experience with my students, who were raised in an entirely anthropocentric worldview, young people in their twenties, at this critical point when they’re making life-defining decisions. And there’s no better way to teach them.

Because no one truly teaches anyone. What we do is facilitate. We facilitate experiences that help them make better decisions for their lives, whether as doctors, lawyers, teachers, anthropologists, or artists, through an experience that brings them to a place that helps them view life, both Western life and local life, through an Amazonian perspective. It allows them to examine globalization and other Western phenomena through Indigenous perspectives.

Oral_narratives_project._Learning_about_the_spirited_forest_photo-3

Credit: Journey Into Amazonia - Florida State University

Natural_History_project._Learning_about_plants._Alpahuayo_Mishana_2014_

Credit: Journey Into Amazonia - Florida State University

So, that’s what happened with the students whose projects involved, for example, studying a plant. They were able to study this plant, but not in the way that traditional education approaches it, not in that fragmentary way. No, that plant does not exist alone. It exists surrounded by people. Because of people. Just as people exist because of the plant, and vice versa. So they had the experience of learning about that plant, but they learned about it through the perspective of the people living in the region.

The same happens if you’re studying a fish. And this also reveals the negative aspects. Like how globalization processes impact a river. How do they transform it? How do they poison it? How do they bring suffering to this fish?

So I believe this was an important experience, and for many years I led this initiative, bringing students to work within these communities. The students lived with people in the communities, with Indigenous people. Or riverside communities. Communities deeply connected to their rivers and forests, who maintain close relationships with them.

As I mentioned earlier, these entities are our most precious companions in life’s fabric, in our journey. The rivers, plants, animals, and clouds—all of them. This is what we’ve forgotten.

Yanayaku_River._Community_Development_project_2011

Credit: Journey Into Amazonia - Florida State University

772ca5d-150630-amazonia_juan-carlos-galeano-710×1024

Mariposa Azul Editions (Portuguese edition)

INDIGENOUS EDUCATION | ACADEMIC BIAS | URGENT ANCESTRAL KNOWLEDGE

Unfortunately, the dominant ideologies in these countries, the racist perspectives based on these representations of the Indigenous world developed by the explorers, were repeated. And then governments repeated these same stories, portraying Indigenous Peoples as primitive.

As a result, the educational systems across Amazon Basin countries also perpetuate this mindset. It suggests these cultures offer nothing to the nation as a whole. Consequently, curricula in primary and secondary schools in the Amazon are developed primarily in these countries’ capitals, at least until recently. In Lima and Bogota.

Just imagine what kind of empowerment or cultural continuity or strengthening of local identities and of their territories can these Indigenous children count on, when forced to follow curricula designed for children from the interior or the Andes?

As for what should be done, society must change. And changing society doesn’t just mean advancing technology. Changing society means transforming how we live. That’s what it requires. So it requires a lot. Of course, learning is always mutual. But right now, we face an urgent situation that compels us to learn from them. We are fighting for our survival, at least for the survival of our species. Because Earth will balance itself and continue on however it must. But we urgently need this ancestral wisdom and traditional ways. These are urgent times.

Connecting the Dots with Juan Carlos Galeano

CtD_JCGaleano_PostCover.001

Credit: FOLIO Festival

Exploring the profound connections between Amazonian cosmogonies, Indigenous knowledge, and environmental stewardship through the lens of the Colombian author, scholar, and environmental advocate.

Born in the Colombian Amazon, Juan Carlos Galeano bridges poetry, academia, and environmental activism with rare authenticity. His work, including “Folktales of the Amazon” and poetry inspired by Amazonian cosmogonies, reveals the intricate relationships between Indigenous, mestizo, and Afro-descendant communities and the forests, rivers, and beings they share their lives with.

At Florida State University, Galeano teaches Latin American poetry while directing “Journey into Amazonia,” a field program in the Peruvian Amazon where students engage directly with local communities and environments rather than just studying them from afar.

We caught up with Juan Carlos at the FOLIO Festival in Óbidos, Portugal, where his book “Amazonia” has just been translated into Portuguese, further extending the reach of these essential Amazonian perspectives.

Play the video version below (English subtitles available), or scroll down for the podcast version (dubbed in English) and for the transcript (in English).

CONNECTING THE DOTS – PODCAST

Are you a podcast fan? Make sure you subscribe to the podcast version of our Connecting the Dots series here.

ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT (TRANSLATION)

INDIGENOUS WORLDVIEWS | KINSHIP | CIVILIZATIONAL CRISIS

In fact, the great value of Indigenous worldviews for our present time is their legacy of wisdom. What sort of wisdom? Well, that wisdom of a relationship with the Earth, entirely different from what we’ve developed in Western culture.

As some Indigenous speakers mentioned earlier today, this wisdom is truly free from dichotomies and dualisms. And, fundamentally, one whereby you feel part of a family with all other beings. That means with the rivers, clouds, water, and air. As if they were our relatives, as expressed in numerous Indigenous cosmogonies. In countless myths and narratives found throughout Indigenous cultures, from each Indigenous people, in which places and other species are considered our relatives.

And as relatives, they teach us better ways to live. When we explore Indigenous narratives, and their concept of interconnected humanity, for example, we find they rest on clear principles. And this is what those principles are based on. On reciprocity. On the profound understanding that we are not alone, we are not independent beings, but rather part of a web of relationships with the whole universe. Not just our immediate surroundings, but the entire universe. I would say these entities are our fellow travelers on life’s journey.

Juan Carlos Galeano y Alfredo Cumapa (Trabajo de campo escuchando historias) en el Amazonas (1998)

Credit: Personal Archive Juan Carlos Galeano

ab11e7_28fdc2b555bc4e6d9e5ea0b193f68beb~mv2.jpg

Credit: Personal Archive Juan Carlos Galeano

So, of course, if this is the legacy of Indigenous cultures, in the current moment, of modernity, it inevitably reemerges. It resurfaces because these voices were silenced by colonialism, neo-colonialism, and modernity, which have decimated not only these voices but the Earth itself.

So, Western culture, seeking narratives that enable self-critique, finds, at this critical moment, these great allies, Indigenous cultures, which preserve the wisdom necessary for the modern world. So I believe this is a fundamental principle,from which we need to begin. And starting point implies respecting and honouring these human communities, who have been marginalized and silenced. In the case of Latin America, for example, through five centuries of colonialism.

So, then, these are narratives, worldviews, that counter all the narratives that were constructed by early explorers, propagated by colonizers, and perpetuated ever since. These narratives form part of a destructive ideology. This is of vital importance in this moment of crisis. A moment of civilizational crisis, as Enrique Leff described it.

ab11e7_785c82bd0ba04facb8e328b6dd7d254a~mv2.jpg

Credit: Personal Archive Juan Carlos Galeano

ab11e7_1041c78246b64b11a13abbe0d31d05f5~mv2.jpg

Credit: Personal Archive Juan Carlos Galeano

AMAZONIAN TALES | RETELLING & REWRITING | IMAGINATION & EMPATHY

Exactly reproducing these tales would require too many pages. So why not create a mythopoetic version of a story, of an oral narrative, that can be captured in just 10 pages? And why shouldn’t we do it through a mythopoetic version? While honoring the original language of these stories. But highlighting those powerful, illuminating moments, almost like epiphanies, that are within these stories.

Besides, no story is ever retold exactly the same way. Because through our imagination, we are always transforming stories. As Italo Calvino said, “A story isn’t beautiful unless you add something new each time you tell it”. Well, as is said in Heraclitus’ aphorism, we never bathe twice in the same river. In a sense, we are the river. We also have what’s called ‘agency’.

So we are always constructing something. We are beings in constant change, like all other beings. We constantly rebuild our imagination. And what happens is that we can manipulate it. We can transcend ourselves. And when we transcend ourselves, we can imagine, we are imaginative enough to do so, how a mountain might think. How might a cloud think? How might a river think? At this point, we enter a completely different set of relationships. We’re creating an entirely different paradigm, because we recognize these entities possess their own subjectivity. Just like we do. And if they have subjectivity like us, then they too are sentient beings.

This allows us to access that other human capacity, which we call compassion, empathy. We can feel with it. Here we enter a kind of society that reconnects with those original societies, we know as Indigenous cultures. If we took time to view the world through our imagination, we might draw closer to the world and feel it more deeply.

810SFpQdXSL._CR0,0,0,130_

Ed.: Libraries Unlimited - Greenwood Publishing Group

FACILITATING EXPERIENCES | AMAZONIAN PERSPECTIVES | SITUATING KNOWLEDGE

Well, I spent many years traveling through rivers and jungles all over the Amazon, through many places, across all the countries of the Basin, and I wanted to share that experience with my students, who were raised in an entirely anthropocentric worldview, young people in their twenties, at this critical point when they’re making life-defining decisions. And there’s no better way to teach them.

Because no one truly teaches anyone. What we do is facilitate. We facilitate experiences that help them make better decisions for their lives, whether as doctors, lawyers, teachers, anthropologists, or artists, through an experience that brings them to a place that helps them view life, both Western life and local life, through an Amazonian perspective. It allows them to examine globalization and other Western phenomena through Indigenous perspectives.

Oral_narratives_project._Learning_about_the_spirited_forest_photo-3

Credit: Journey Into Amazonia - Florida State University

Natural_History_project._Learning_about_plants._Alpahuayo_Mishana_2014_

Credit: Journey Into Amazonia - Florida State University

So, that’s what happened with the students whose projects involved, for example, studying a plant. They were able to study this plant, but not in the way that traditional education approaches it, not in that fragmentary way. No, that plant does not exist alone. It exists surrounded by people. Because of people. Just as people exist because of the plant, and vice versa. So they had the experience of learning about that plant, but they learned about it through the perspective of the people living in the region.

The same happens if you’re studying a fish. And this also reveals the negative aspects. Like how globalization processes impact a river. How do they transform it? How do they poison it? How do they bring suffering to this fish?

So I believe this was an important experience, and for many years I led this initiative, bringing students to work within these communities. The students lived with people in the communities, with Indigenous people. Or riverside communities. Communities deeply connected to their rivers and forests, who maintain close relationships with them.

As I mentioned earlier, these entities are our most precious companions in life’s fabric, in our journey. The rivers, plants, animals, and clouds—all of them. This is what we’ve forgotten.

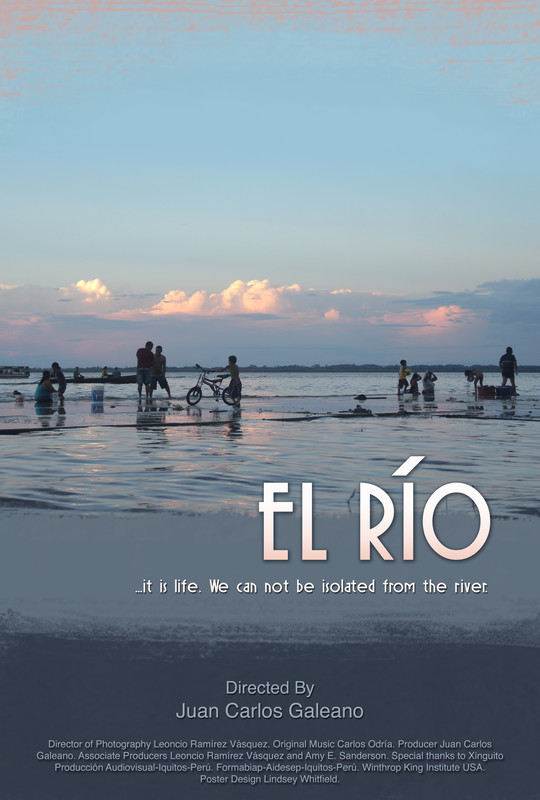

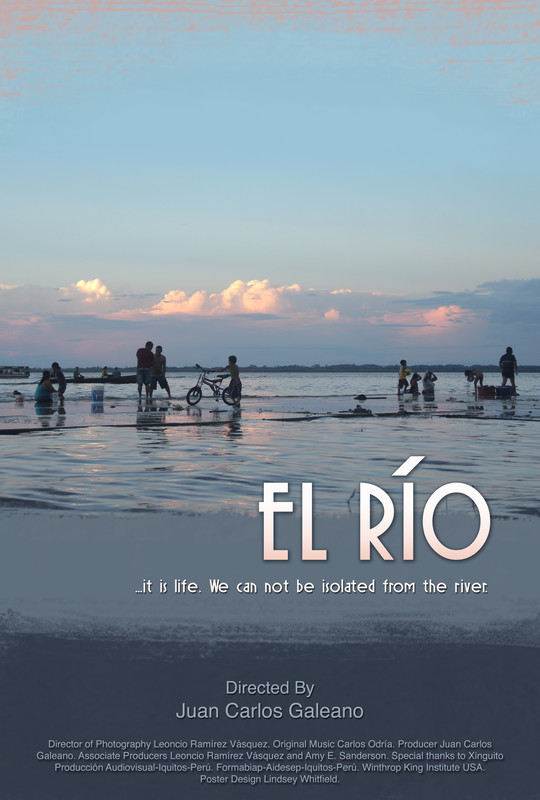

Yanayaku_River._Community_Development_project_2011

Credit: Journey Into Amazonia - Florida State University

772ca5d-150630-amazonia_juan-carlos-galeano-710×1024

Mariposa Azul Editions (Portuguese edition)

INDIGENOUS EDUCATION | ACADEMIC BIAS | URGENT ANCESTRAL KNOWLEDGE

Unfortunately, the dominant ideologies in these countries, the racist perspectives based on these representations of the Indigenous world developed by the explorers, were repeated. And then governments repeated these same stories, portraying Indigenous Peoples as primitive.

As a result, the educational systems across Amazon Basin countries also perpetuate this mindset. It suggests these cultures offer nothing to the nation as a whole. Consequently, curricula in primary and secondary schools in the Amazon are developed primarily in these countries’ capitals, at least until recently. In Lima and Bogota.

Just imagine what kind of empowerment or cultural continuity or strengthening of local identities and of their territories can these Indigenous children count on, when forced to follow curricula designed for children from the interior or the Andes?

As for what should be done, society must change. And changing society doesn’t just mean advancing technology. Changing society means transforming how we live. That’s what it requires. So it requires a lot. Of course, learning is always mutual. But right now, we face an urgent situation that compels us to learn from them. We are fighting for our survival, at least for the survival of our species. Because Earth will balance itself and continue on however it must. But we urgently need this ancestral wisdom and traditional ways. These are urgent times.