Connecting the Dots with Ellen Pirá Wassu

Indigenous literature as resistance and celebration: A conversation with the artivist and poet on decolonization, reparations, and finding joy in the struggle.

In recent years, we’ve witnessed a remarkable transformation in the landscape of Indigenous literature. Diverse voices, long muted by the constraints of non-Indigenous literary traditions, are now emerging with profound resonance and undeniable urgency. Our understanding of the world we inhabit can no longer overlook the vital contributions of Indigenous worldviews and the lived experiences of authors who embody these identities. As our guest today, Ellen Pirá Wassu, powerfully articulates, Indigenous literature serves as an essential instrument “of resistance and re-enchantment”, a crucial means of postponing the end of the world.

Ellen exemplifies this transformative literary movement, weaving together poetry, performance and activism in a practice that honours both the written word and deeper forms of knowing – what she beautifully describes as “river bathing and talking with flowers”. Currently pursuing her doctorate in Comparative Modernities at the University of Minho, Ellen has enriched the literary landscape with two significant works published by Urutau: “ixé ygara voltando pra ‘y’kûá” and “yby kûatiara um livro de terra“.

We were honoured to engage with Ellen during FOLIO – the Óbidos International Literary Festival, in Portugal, where we also participated in a round table discussion exploring world configurations and the vital role of Indigenous worldviews in imagining possible futures. The conversation we share here extends far beyond conventional literary discourse. It invites us to fundamentally reconsider our relationship with language and the world we inhabit.

Ellen will also be participating in “Roots of the Future – A Dialogue with Indigenous Peoples and Allies on Culture, the Environment and Rights”, and event organized by Azimuth World Foundation, taking place on January 11, 2025, in Pavilhão do Conhecimento (Lisbon, Portugal).

Play the video version below (English subtitles available), or scroll down for the podcast version (dubbed in English) and for the transcript (in English).

CONNECTING THE DOTS – PODCAST

Are you a podcast fan? Make sure you subscribe to the podcast version of our Connecting the Dots series here.

ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT (TRANSLATION)

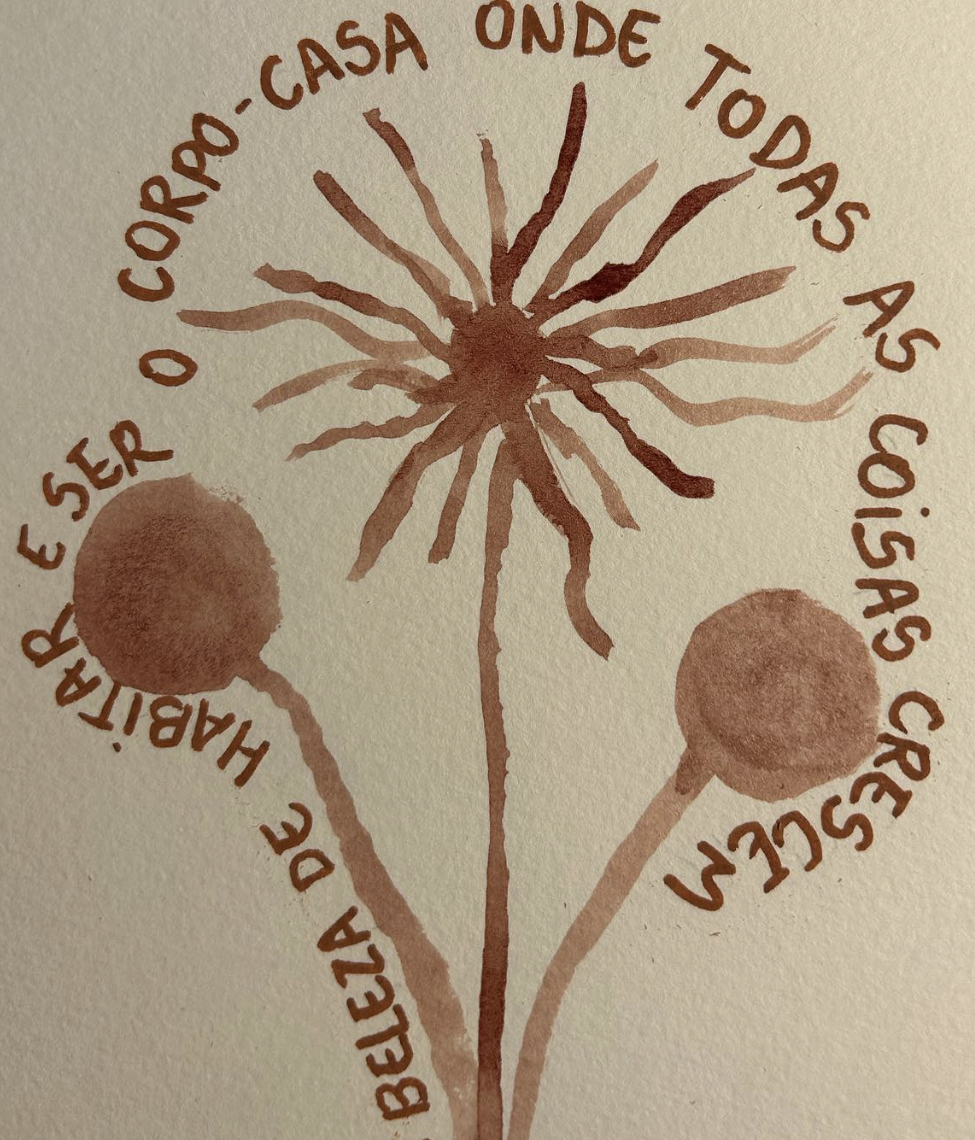

Screenshot 2024-12-03 at 10.54.17

Credit: Ellen Wassu - Instagram (@ellenlimawassu)

“ixé ygara voltando pra ‘y’kûá” was the first book I published. And the second one is called “yby kûatiara um livro de terra”. Both books are partly in Tupi, an ancestral language that was silenced by the Marquis of Pombal in the 18th century. They were very much a process of bringing back this ancestral language, of awakening this ancestral language within me. But being in this territory and writing in this language that was intentionally silenced was also a political position, one that I assumed within the field of literature, within my artistic, literary practice.

My identity is fragmented and broken by colonization, by the colonial process. My ancestral language is not currently spoken in my territory. Because four centuries of direct contact with colonization meant that we stopped speaking the language. We stopped practicing specific cultural manifestations that were intensely persecuted during the colonial process.

Therefore, when I bring my literature here, in addition to the many ways it speaks of the Earth, the spirit of the Earth, this beautiful thing that speaks through us, it also comes from a deeply political place. Here, where I am – and I know exactly who this body is in this territory, in this space here – everything I do, everything I bring is so that this memory can be brought up in this specific place. Because there is a monumentalization in Portugal of what people here call “descobrimentos” (discoveries), and which we call “invasion”. Being here, and affirming my position through my ancestral language, and through my body, is also a way of saying that I am alive.

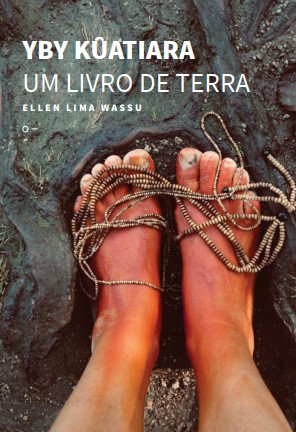

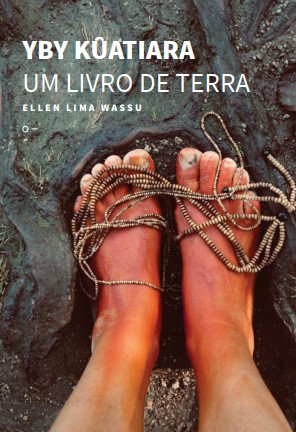

capa_yby-kuatiara

Credit: Urutau

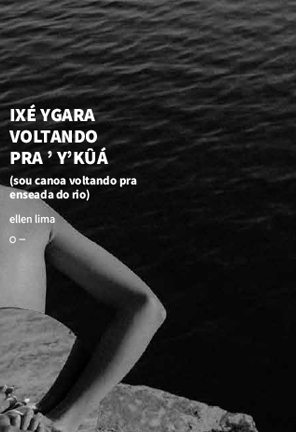

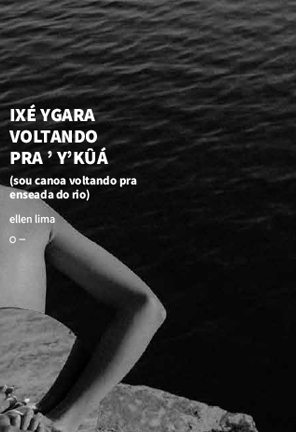

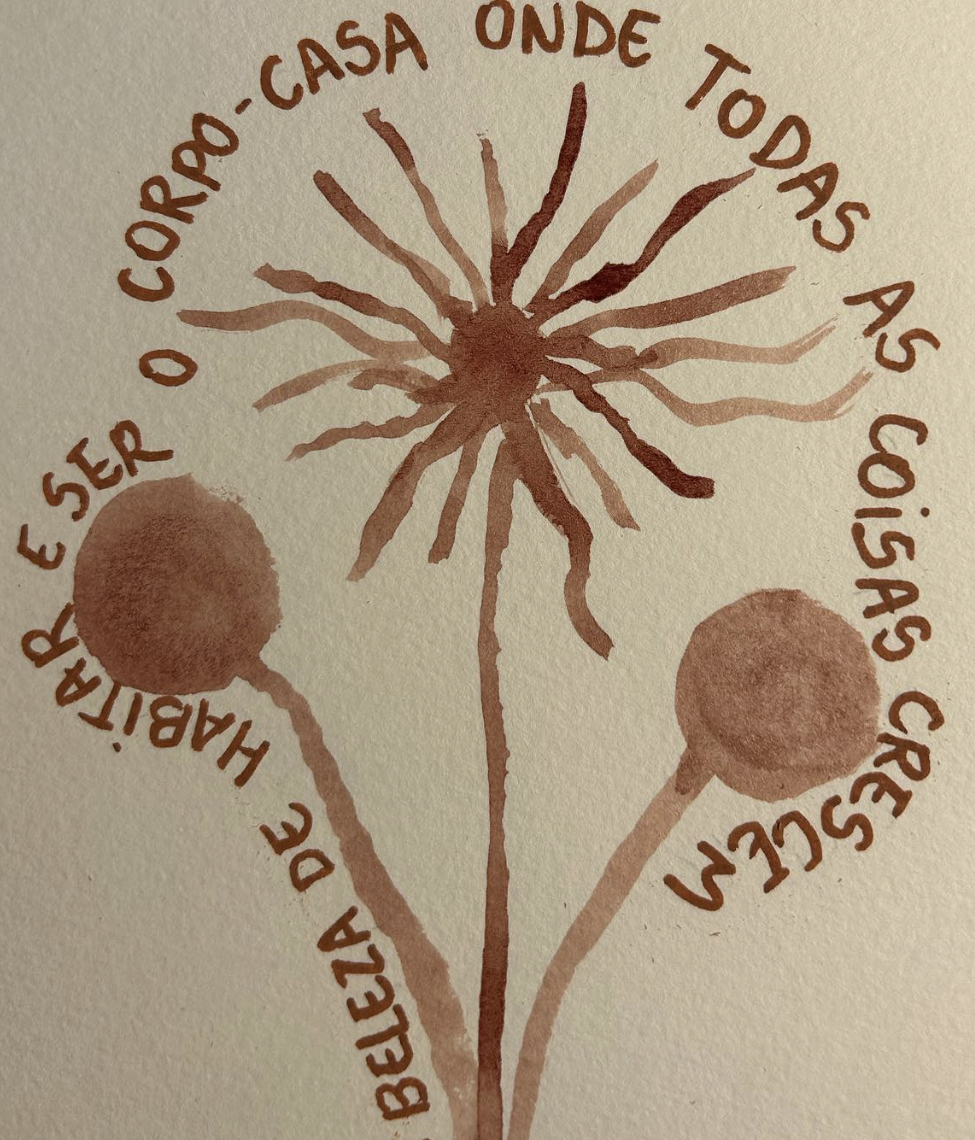

lima_capa

Credit: Urutau

And the poetics of expropriation, which is something I develop in my academic work, in my doctoral research, comes very much from the perception of a fragmented, broken identity. I was born and raised on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro. And my family, my ancestral territory, is in Alagoas. So I grew up, I started out, fragmented in many ways.

And I think that the way Indigenous people are represented, the way Indigenous people have been represented since the onset of colonization, has been and continues to be a disservice to us. Because we don’t recognize ourselves in those images. That’s why I call them “poetics of expropriation”, because not only do I not recognize myself in those images, they also take away my sense of identity in the present.

I know who I am, but books in school told a different story about me, advertising tells a different story about me. I’m not what they say I am. They represent me in ways that are not me. And I call this poetics, all these representations, the “poetics of expropriation”. Because that’s what it does. It strips away Indigenous identity, so that afterwards it can state: “You are no longer Indigenous”. And with that, it can take away our land and take away our land rights.

So I’m also affirming that we are Indigenous anywhere. We are Indigenous people when we are part of a diaspora, we are Indigenous people when we are pursuing a doctorate in Portugal, we are Indigenous people anywhere. And we are here precisely to reclaim our own image. Precisely to reclaim our image and say: “We have autonomy, and we’re going to be in charge of this representation”.

Screenshot 2024-12-03 at 10.57.16

Credit: Ellen Wassu - Instagram (@ellenlimawassu)

IMG_3305

At Folio Festival, in Óbidos, Portugal (2024)

DECOLONIZING | UNLEARNING | BECOMING AWARE

When you create a discourse, a discourse that doesn’t hold up, a discourse that isn’t true, or one that doesn’t even take into account the vision of who is being represented, then, in fact, you’re not able to see things as they are. Something is standing in front of you, perhaps a veil, something that doesn’t allow you to understand.

So decolonization – I don’t like the word – but it’s a kind of “veil”. There’s an unveiling when we stop to think about the impacts of colonization, when we strive to understand how colonial narratives are built within our society. And when I think about the way it happens in Portugal, when I read the school textbooks, and listen to people in my circles here, I can see the memorialization of the “descobrimentos” (discoveries), as it is called here, limiting and reducing the capacities of a population, of a people, in a country that is absolutely abundant, in terms of land, sun, everything.

But when you see the world through the prism of colonization, through this lens that is based on pride for having colonized… In my opinion, it’s a senseless pride, because it’s a genocidal pride. What are you proud of? What is there to be proud of? Is it pride in having invaded territories and decimated cultures? That’s not what pride should be built upon. So I think part of decolonizing is also decolonizing yourself.

It also means no longer valuing colonization as a domination project. And start valuing the land. Because Portugal is a very fertile land, even from an European, economic point of view. Things are planted and grow here, which are consumed everywhere. So why is it that instead of being proud of the land, you’d choose to be proud of colonizers and invaders?

Screenshot 2024-12-03 at 10.53.34

Credit: Ellen Wassu - Instagram (@ellenlimawassu)

Screenshot 2024-12-03 at 10.57.07

Credit: Ellen Wassu - Instagram (@ellenlimawassu)

That’s why it is obvious and crucial that Indigenous voices are brought in, as well as Roma voices, black voices, female voices, trans voices, you name it. Because this is the world we’re living in. And we can only construct ourselves by deconstructing what we have learned as rules and norms.

I always mention one of the poems in my latest book, titled “desaprendências” (unlearnings). It goes like this: “To forget what has been learned. To relearn what was deemed known. Truth is not Western, and the idea of normal is a desert of absences. To unlearn, distractedly or attentively, can a being awake”. I feel that when we start to think about decolonization, when we learn how to decolonize ourselves, and learn to look at certain attitudes and discourses as if they are not familiar to us, then we learn to look at ourselves much more attentively and much more truthfully.

This is something I repeat all the time: we are part of an economic model, of a system that eats up land, eats up people, eats up life, spirit and joy. And we’re trapped in it. And the production of this discourse, it all stems from this colonial, patriarchal heritage. And if we normalize it and we keep repeating these things, we’ll stay stuck in the same place.

If you don’t give a plant space to grow, it won’t grow. And that’s kind of what I think decolonization is, what the decolonization process is. When we remove these lenses, these lenses that constrain our roots to a tiny pot, when we expand that way, we are able to grow and flourish, we are able to generate something else.

And I have a lot of confidence in people. But I think it’s critical that we avoid romanticizing: we are trapped in a system, and these discourses it produces are discourses that imprison us. So we are trapped. And what can we do about that? How do we release ourselves from these shackles? We decolonize ourselves.

462619560_1072637244231513_7068576347785019759_n

Credit: FOLIO Festival

462809526_1072637294231508_6345238791409643048_n

Credit: FOLIO Festival

And that’s where I think the worldviews and ways of knowing found in traditional and Indigenous communities, developed by people that are outside this system, outside this model that has been handed to us as the truth… If we start looking at the world from those viewpoints, maybe our way of looking at the world can become more attentive and caring, and include in it what is fragile and challenging. Because, deep down, we are built upon a fiction. And this Western fiction hurts and bruises us. It lies to us. And we are founded upon it, we are born in it, we don’t choose it.

And I believe decolonization, and what Indigenous Peoples are discussing nowadays in Brazil, which is counter-colonization, something that goes beyond decolonization, is about becoming aware. I believe we have to rethink our practices.

I think it’s crucial that we no longer build discourses that don’t include everyone’s participation. In Brazil today, Indigenous and territorial issues are being discussed without Indigenous people having a seat at the table. The National Congress decides on its own. We’re discussing women’s reproductive rights without women at the table, without people with uteruses at the table.

So how do we fight this? We bring in these other voices, and we make a point of not taking the spotlight for a while. And I think now is the time for us to listen to each other, and listen to the Earth, listen to other things. To get to know other worlds and unlearn. And by unlearning, we go out into the world.

EXTERNAL LINK

REPARATIONS | RESPONSIBILITY | TEACHING HOW TO BE

Regarding the topic of “historical debts”, I believe many things need to be taken into consideration. Denise Ferreira da Silva has a book in which she says: “It’s an unpayable debt”. My language is buried, my culture has been decimated. We are part of a resistance, because we keep resisting. But there is no possible payment for this debt. But the fact that there is no possible payment doesn’t mean that we should sit back and do nothing about it.

So I think that, especially people who are in a position of power, and who are in a position to amplify, they have the right and the duty to do just that: to add more voices to the conversation. I think that’s exactly what they should do. Bring these voices in, listen to them, amplify them. It goes far beyond a historical debt. We are living in the present. I’m here. There is xenophobic discourse. There is racist discourse. They exist. And this is deeply rooted in society.

So I feel like it’s about taking responsibility, but not in the collective sense. It’s about individual responsibility, especially for people who are in positions of power, and who have the means to build these bridges. Wanting to do that, having the will to do it, that’s where I feel like it’s a question of individual responsibility and accountability.

I heard this somewhere, but I can’t remember who said it: “We don’t teach what we know. We teach what we are”. So we need to be. We need to be anti-racist. We need to be supportive. We need to fight back. And we genuinely need to be the example for the next generations.

I feel like reparations, from the point of view of someone living day-to-day as an immigrant, would be for a Portuguese person sitting at a table, next to a foreigner, not treating that person as different, as a Brazilian. or an Indian. “Look at me as I am. With the human constitution I’m made of, as you are also.” For me, this is in fact the greatest form of reparation.

I believe there are different levels of knowledge production. I’m here on an academic level, on a poetic level, on an artistic level. But I’m also a primary teacher. I worked in primary schools for 10 years of my life back in Brazil. And there are many parts of society that need that education, where this discourse must reach.

So I think the real reparations start by looking honestly at our practices. And by standing up against what really needs to be reprimanded, with the authority of someone who wants to build a better world.

Screenshot 2024-12-03 at 10.52.26

Credit: Ellen Wassu - Instagram (@ellenlimawassu)

Screenshot 2024-12-03 at 10.58.40

Credit: Ellen Wassu - Instagram (@ellenlimawassu)

THE STRUGGLE | ANGER AND JOY | ALLYSHIP

We’re also living in a media age. Which, on the one hand, is wonderful. Because I can spread the word about important things. People who are working for the Earth are able to do their work and publicize it. But we also see an enormous growth of fascist-leaning groups.

So when this gentleman published his article in the newspaper, saying that, “It was the Portuguese who taught Indigenous Peoples how to take care of the forest, not the other way around”, it was still rooted in the assumption that there is a civilizational superiority. He’s assuming that he belongs to a superior humanity, and that he really needs to enlighten the world with his wisdom.

I have a lot of anger. I say this all the time. I work with anger, I write with anger, I speak with anger. And I’ve felt a lot of anger about this, just as I feel anger about many things I see out there. But that’s exactly what I try to do: I don’t think we should ever shut down the dialogue, because we’re also living through a time of extreme polarization. But I can’t jeopardize my self-care in that process. Because I’ll become sick, if I can only respond with anger. And that’s not something I intend to do.

And I feel like these discourses that are produced come from a completely distorted understanding of what one’s own place is. So I feel that fighting back is the answer. I feel like responding is the answer, whenever I’m well enough to do it. But I must add: I call on everyone to respond along with me. Because I’m alone, responding.

This happens to me a lot, because I’m one of the few Indigenous people here, one of the few Indigenous voices, and everyone keeps sharing this stuff with me: “Did you see what so-and-so did? Look at this”. There’s a gym in Portugal, it’s been a few months now, they did a redface. And people were warning me about it. And I was going through a very challenging time, I had a lot of work on my hands. I can’t take that on as well. You don’t have to send this information to me and say, “Look, Ellen, respond to this”. Everyone is responsible for doing so. And I believe speaking out is important. I’m here for it. And I want my voice to reach out, I want the word to spread. The word must travel for sure. But I feel that we also have to take responsibility for this fight.

I mean, what is the ideal? For me, the ideal is the end of a regime that eats up the planet. But since we are living in it, and I mean whoever is awake, and whoever is distressed, and whoever is looking at the world, saying: “This is wrong”, whoever has already woken up, we have no other choice. Those who have woken up are in the fight. And we have an obligation, a duty, to fight.

And also to be cheerful and happy. We have an obligation to fight back, and we also have an obligation to be happy. As Nêgo Bispo, a quilombola intellectual from Brazil, says, “It’s about organizing anger and defending joy”. I have a lot of anger, and I’m here in this world taking action. But if I don’t defend my joy, if I don’t defend my spirit, if I don’t defend what’s good in my heart, then that doesn’t work either.

So we need to strike a balance. We must take part in the struggle and take part in the samba. We must participate in public discourse and, at the same time, we must bathe in the sea, or chat with our friends. And we must do so while getting out of this imprisoning structure, while imagining other worlds. Love is a force that can somehow free us from that. When you’re in love, when you’re in love with someone, you reach an almost sublime state. And that’s because love takes us away from the madness of overwhelming reality. But if you think about it, that’s what poetry is. And if we keep the poetry’s flame alive within us, if we let it fuel us, we are able to balance out the anger, and we are able to love, and we find a way to balance it all out. But we do so through anger, joy and love. And through organization and political struggle, always.

Connecting the Dots with Ellen Pirá Wassu

Indigenous literature as resistance and celebration: A conversation with the artivist and poet on decolonization, reparations, and finding joy in the struggle.

In recent years, we’ve witnessed a remarkable transformation in the landscape of Indigenous literature. Diverse voices, long muted by the constraints of non-Indigenous literary traditions, are now emerging with profound resonance and undeniable urgency. Our understanding of the world we inhabit can no longer overlook the vital contributions of Indigenous worldviews and the lived experiences of authors who embody these identities. As our guest today, Ellen Pirá Wassu, powerfully articulates, Indigenous literature serves as an essential instrument “of resistance and re-enchantment”, a crucial means of postponing the end of the world.

Ellen exemplifies this transformative literary movement, weaving together poetry, performance and activism in a practice that honours both the written word and deeper forms of knowing – what she beautifully describes as “river bathing and talking with flowers”. Currently pursuing her doctorate in Comparative Modernities at the University of Minho, Ellen has enriched the literary landscape with two significant works published by Urutau: “ixé ygara voltando pra ‘y’kûá” and “yby kûatiara um livro de terra“.

We were honoured to engage with Ellen during FOLIO – the Óbidos International Literary Festival, in Portugal, where we also participated in a round table discussion exploring world configurations and the vital role of Indigenous worldviews in imagining possible futures. The conversation we share here extends far beyond conventional literary discourse. It invites us to fundamentally reconsider our relationship with language and the world we inhabit.

Ellen will also be participating in “Roots of the Future – A Dialogue with Indigenous Peoples and Allies on Culture, the Environment and Rights”, and event organized by Azimuth World Foundation, taking place on January 11, 2025, in Pavilhão do Conhecimento (Lisbon, Portugal).

Play the video version below (English subtitles available), or scroll down for the podcast version (dubbed in English) and for the transcript (in English).

CONNECTING THE DOTS – PODCAST

Are you a podcast fan? Make sure you subscribe to the podcast version of our Connecting the Dots series here.

ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT (TRANSLATION)

Screenshot 2024-12-03 at 10.54.17

Credit: Ellen Wassu - Instagram (@ellenlimawassu)

“ixé ygara voltando pra ‘y’kûá” was the first book I published. And the second one is called “yby kûatiara um livro de terra”. Both books are partly in Tupi, an ancestral language that was silenced by the Marquis of Pombal in the 18th century. They were very much a process of bringing back this ancestral language, of awakening this ancestral language within me. But being in this territory and writing in this language that was intentionally silenced was also a political position, one that I assumed within the field of literature, within my artistic, literary practice.

My identity is fragmented and broken by colonization, by the colonial process. My ancestral language is not currently spoken in my territory. Because four centuries of direct contact with colonization meant that we stopped speaking the language. We stopped practicing specific cultural manifestations that were intensely persecuted during the colonial process.

Therefore, when I bring my literature here, in addition to the many ways it speaks of the Earth, the spirit of the Earth, this beautiful thing that speaks through us, it also comes from a deeply political place. Here, where I am – and I know exactly who this body is in this territory, in this space here – everything I do, everything I bring is so that this memory can be brought up in this specific place. Because there is a monumentalization in Portugal of what people here call “descobrimentos” (discoveries), and which we call “invasion”. Being here, and affirming my position through my ancestral language, and through my body, is also a way of saying that I am alive.

capa_yby-kuatiara

Credit: Urutau

lima_capa

Credit: Urutau

And the poetics of expropriation, which is something I develop in my academic work, in my doctoral research, comes very much from the perception of a fragmented, broken identity. I was born and raised on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro. And my family, my ancestral territory, is in Alagoas. So I grew up, I started out, fragmented in many ways.

And I think that the way Indigenous people are represented, the way Indigenous people have been represented since the onset of colonization, has been and continues to be a disservice to us. Because we don’t recognize ourselves in those images. That’s why I call them “poetics of expropriation”, because not only do I not recognize myself in those images, they also take away my sense of identity in the present.

I know who I am, but books in school told a different story about me, advertising tells a different story about me. I’m not what they say I am. They represent me in ways that are not me. And I call this poetics, all these representations, the “poetics of expropriation”. Because that’s what it does. It strips away Indigenous identity, so that afterwards it can state: “You are no longer Indigenous”. And with that, it can take away our land and take away our land rights.

So I’m also affirming that we are Indigenous anywhere. We are Indigenous people when we are part of a diaspora, we are Indigenous people when we are pursuing a doctorate in Portugal, we are Indigenous people anywhere. And we are here precisely to reclaim our own image. Precisely to reclaim our image and say: “We have autonomy, and we’re going to be in charge of this representation”.

Screenshot 2024-12-03 at 10.57.16

Credit: Ellen Wassu - Instagram (@ellenlimawassu)

IMG_3305

At Folio Festival, in Óbidos, Portugal (2024)

DECOLONIZING | UNLEARNING | BECOMING AWARE

When you create a discourse, a discourse that doesn’t hold up, a discourse that isn’t true, or one that doesn’t even take into account the vision of who is being represented, then, in fact, you’re not able to see things as they are. Something is standing in front of you, perhaps a veil, something that doesn’t allow you to understand.

So decolonization – I don’t like the word – but it’s a kind of “veil”. There’s an unveiling when we stop to think about the impacts of colonization, when we strive to understand how colonial narratives are built within our society. And when I think about the way it happens in Portugal, when I read the school textbooks, and listen to people in my circles here, I can see the memorialization of the “descobrimentos” (discoveries), as it is called here, limiting and reducing the capacities of a population, of a people, in a country that is absolutely abundant, in terms of land, sun, everything.

But when you see the world through the prism of colonization, through this lens that is based on pride for having colonized… In my opinion, it’s a senseless pride, because it’s a genocidal pride. What are you proud of? What is there to be proud of? Is it pride in having invaded territories and decimated cultures? That’s not what pride should be built upon. So I think part of decolonizing is also decolonizing yourself.

It also means no longer valuing colonization as a domination project. And start valuing the land. Because Portugal is a very fertile land, even from an European, economic point of view. Things are planted and grow here, which are consumed everywhere. So why is it that instead of being proud of the land, you’d choose to be proud of colonizers and invaders?

Screenshot 2024-12-03 at 10.53.34

Credit: Ellen Wassu - Instagram (@ellenlimawassu)

Screenshot 2024-12-03 at 10.57.07

Credit: Ellen Wassu - Instagram (@ellenlimawassu)

That’s why it is obvious and crucial that Indigenous voices are brought in, as well as Roma voices, black voices, female voices, trans voices, you name it. Because this is the world we’re living in. And we can only construct ourselves by deconstructing what we have learned as rules and norms.

I always mention one of the poems in my latest book, titled “desaprendências” (unlearnings). It goes like this: “To forget what has been learned. To relearn what was deemed known. Truth is not Western, and the idea of normal is a desert of absences. To unlearn, distractedly or attentively, can a being awake”. I feel that when we start to think about decolonization, when we learn how to decolonize ourselves, and learn to look at certain attitudes and discourses as if they are not familiar to us, then we learn to look at ourselves much more attentively and much more truthfully.

This is something I repeat all the time: we are part of an economic model, of a system that eats up land, eats up people, eats up life, spirit and joy. And we’re trapped in it. And the production of this discourse, it all stems from this colonial, patriarchal heritage. And if we normalize it and we keep repeating these things, we’ll stay stuck in the same place.

If you don’t give a plant space to grow, it won’t grow. And that’s kind of what I think decolonization is, what the decolonization process is. When we remove these lenses, these lenses that constrain our roots to a tiny pot, when we expand that way, we are able to grow and flourish, we are able to generate something else.

And I have a lot of confidence in people. But I think it’s critical that we avoid romanticizing: we are trapped in a system, and these discourses it produces are discourses that imprison us. So we are trapped. And what can we do about that? How do we release ourselves from these shackles? We decolonize ourselves.

462619560_1072637244231513_7068576347785019759_n

Credit: FOLIO Festival

462809526_1072637294231508_6345238791409643048_n

Credit: FOLIO Festival

And that’s where I think the worldviews and ways of knowing found in traditional and Indigenous communities, developed by people that are outside this system, outside this model that has been handed to us as the truth… If we start looking at the world from those viewpoints, maybe our way of looking at the world can become more attentive and caring, and include in it what is fragile and challenging. Because, deep down, we are built upon a fiction. And this Western fiction hurts and bruises us. It lies to us. And we are founded upon it, we are born in it, we don’t choose it.

And I believe decolonization, and what Indigenous Peoples are discussing nowadays in Brazil, which is counter-colonization, something that goes beyond decolonization, is about becoming aware. I believe we have to rethink our practices.

I think it’s crucial that we no longer build discourses that don’t include everyone’s participation. In Brazil today, Indigenous and territorial issues are being discussed without Indigenous people having a seat at the table. The National Congress decides on its own. We’re discussing women’s reproductive rights without women at the table, without people with uteruses at the table.

So how do we fight this? We bring in these other voices, and we make a point of not taking the spotlight for a while. And I think now is the time for us to listen to each other, and listen to the Earth, listen to other things. To get to know other worlds and unlearn. And by unlearning, we go out into the world.

EXTERNAL LINK

REPARATIONS | RESPONSIBILITY | TEACHING HOW TO BE

Regarding the topic of “historical debts”, I believe many things need to be taken into consideration. Denise Ferreira da Silva has a book in which she says: “It’s an unpayable debt”. My language is buried, my culture has been decimated. We are part of a resistance, because we keep resisting. But there is no possible payment for this debt. But the fact that there is no possible payment doesn’t mean that we should sit back and do nothing about it.

So I think that, especially people who are in a position of power, and who are in a position to amplify, they have the right and the duty to do just that: to add more voices to the conversation. I think that’s exactly what they should do. Bring these voices in, listen to them, amplify them. It goes far beyond a historical debt. We are living in the present. I’m here. There is xenophobic discourse. There is racist discourse. They exist. And this is deeply rooted in society.

So I feel like it’s about taking responsibility, but not in the collective sense. It’s about individual responsibility, especially for people who are in positions of power, and who have the means to build these bridges. Wanting to do that, having the will to do it, that’s where I feel like it’s a question of individual responsibility and accountability.

I heard this somewhere, but I can’t remember who said it: “We don’t teach what we know. We teach what we are”. So we need to be. We need to be anti-racist. We need to be supportive. We need to fight back. And we genuinely need to be the example for the next generations.

I feel like reparations, from the point of view of someone living day-to-day as an immigrant, would be for a Portuguese person sitting at a table, next to a foreigner, not treating that person as different, as a Brazilian. or an Indian. “Look at me as I am. With the human constitution I’m made of, as you are also.” For me, this is in fact the greatest form of reparation.

I believe there are different levels of knowledge production. I’m here on an academic level, on a poetic level, on an artistic level. But I’m also a primary teacher. I worked in primary schools for 10 years of my life back in Brazil. And there are many parts of society that need that education, where this discourse must reach.

So I think the real reparations start by looking honestly at our practices. And by standing up against what really needs to be reprimanded, with the authority of someone who wants to build a better world.

Screenshot 2024-12-03 at 10.52.26

Credit: Ellen Wassu - Instagram (@ellenlimawassu)

Screenshot 2024-12-03 at 10.58.40

Credit: Ellen Wassu - Instagram (@ellenlimawassu)

THE STRUGGLE | ANGER AND JOY | ALLYSHIP

We’re also living in a media age. Which, on the one hand, is wonderful. Because I can spread the word about important things. People who are working for the Earth are able to do their work and publicize it. But we also see an enormous growth of fascist-leaning groups.

So when this gentleman published his article in the newspaper, saying that, “It was the Portuguese who taught Indigenous Peoples how to take care of the forest, not the other way around”, it was still rooted in the assumption that there is a civilizational superiority. He’s assuming that he belongs to a superior humanity, and that he really needs to enlighten the world with his wisdom.

I have a lot of anger. I say this all the time. I work with anger, I write with anger, I speak with anger. And I’ve felt a lot of anger about this, just as I feel anger about many things I see out there. But that’s exactly what I try to do: I don’t think we should ever shut down the dialogue, because we’re also living through a time of extreme polarization. But I can’t jeopardize my self-care in that process. Because I’ll become sick, if I can only respond with anger. And that’s not something I intend to do.

And I feel like these discourses that are produced come from a completely distorted understanding of what one’s own place is. So I feel that fighting back is the answer. I feel like responding is the answer, whenever I’m well enough to do it. But I must add: I call on everyone to respond along with me. Because I’m alone, responding.

This happens to me a lot, because I’m one of the few Indigenous people here, one of the few Indigenous voices, and everyone keeps sharing this stuff with me: “Did you see what so-and-so did? Look at this”. There’s a gym in Portugal, it’s been a few months now, they did a redface. And people were warning me about it. And I was going through a very challenging time, I had a lot of work on my hands. I can’t take that on as well. You don’t have to send this information to me and say, “Look, Ellen, respond to this”. Everyone is responsible for doing so. And I believe speaking out is important. I’m here for it. And I want my voice to reach out, I want the word to spread. The word must travel for sure. But I feel that we also have to take responsibility for this fight.

I mean, what is the ideal? For me, the ideal is the end of a regime that eats up the planet. But since we are living in it, and I mean whoever is awake, and whoever is distressed, and whoever is looking at the world, saying: “This is wrong”, whoever has already woken up, we have no other choice. Those who have woken up are in the fight. And we have an obligation, a duty, to fight.

And also to be cheerful and happy. We have an obligation to fight back, and we also have an obligation to be happy. As Nêgo Bispo, a quilombola intellectual from Brazil, says, “It’s about organizing anger and defending joy”. I have a lot of anger, and I’m here in this world taking action. But if I don’t defend my joy, if I don’t defend my spirit, if I don’t defend what’s good in my heart, then that doesn’t work either.

So we need to strike a balance. We must take part in the struggle and take part in the samba. We must participate in public discourse and, at the same time, we must bathe in the sea, or chat with our friends. And we must do so while getting out of this imprisoning structure, while imagining other worlds. Love is a force that can somehow free us from that. When you’re in love, when you’re in love with someone, you reach an almost sublime state. And that’s because love takes us away from the madness of overwhelming reality. But if you think about it, that’s what poetry is. And if we keep the poetry’s flame alive within us, if we let it fuel us, we are able to balance out the anger, and we are able to love, and we find a way to balance it all out. But we do so through anger, joy and love. And through organization and political struggle, always.