Connecting the Dots with Dr. Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

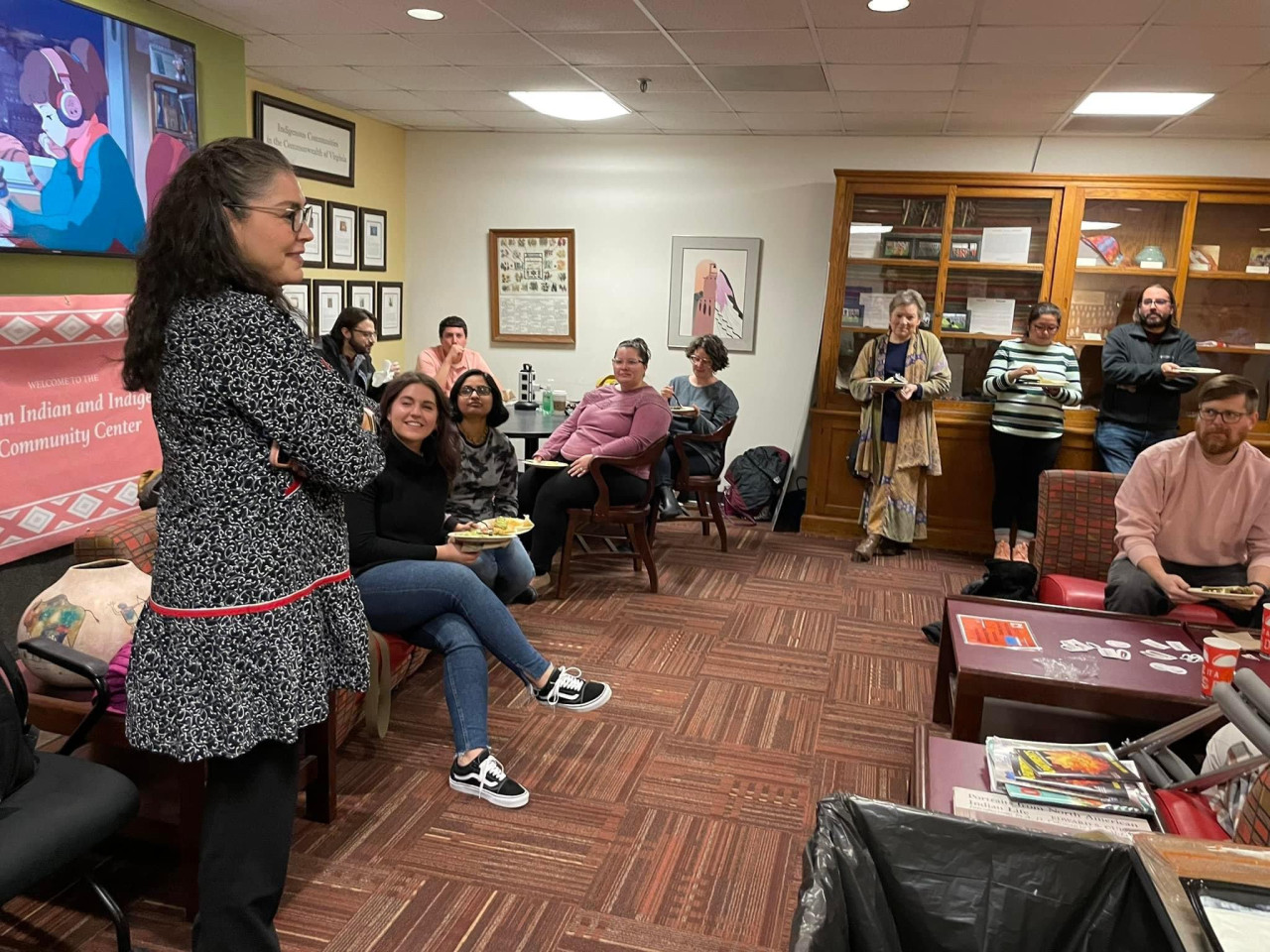

With our two guests, sisters and collaborators spearheading the Respectful Research intiative, we explore a decolonizing approach to Arctic research.

In a recent episode of our podcast, we had an enlightening conversation with Iñupiaq Conservation Biologist Dr. Victoria Buschman about the role of Arctic Indigenous communities in shaping conservation strategies.

Today, we are expanding upon our previous discussion to more deeply explore a decolonizing approach to Arctic research in general. Furthermore, we aim to examine how this approach can be applied within institutional settings at the community level. We are privileged to have not just one, but two highly knowledgeable guests joining us for this episode: Dr. Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer, who are not only sisters but also collaborators currently spearheading the groundbreaking Respectful Research intiative.

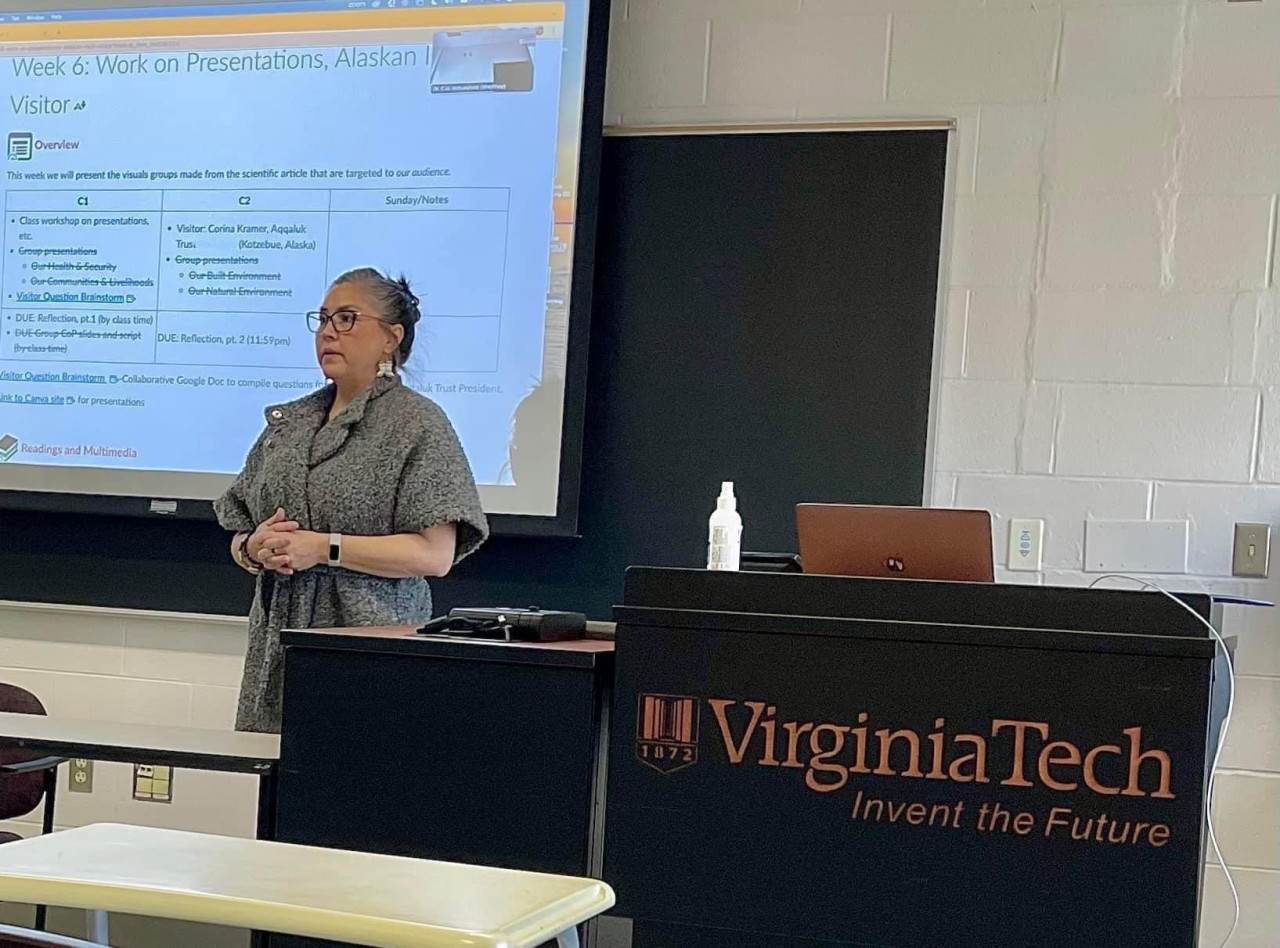

Dr. Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq is assistant professor of technical and scientific communication at Virginia Tech. Cana is Iñupiaq, from Northwest Alaska and an enrolled member of the Noorvik Native Community. The digital humanities, data analysis, critical race theory, and Indigenous knowledges are combined in Cana’s research, in order to investigate the intersections of identity, science/technology/medicine, colonialism, and culture. Their work sheds light on how the marginalization of underrepresented scholars and communities is often perpetuated in mainstream academic, institutional, and societal practice. Using theory and data, they aim to craft methodologies that empower others to undertake research and engage in social justice work with respect and sensitivity, particularly in the realm of technical communication and other disciplines.

Corina Qaaġraq Kramer, also of Iñupiaq descent, hails from the Native Village of Kotzebue. As a community leader with extensive frontline experience, Corina brings a unique expertise to her work, specializing in bridging traditional Indigenous knowledge and values with Western institutional practices to enhance the well-being of Native communities, health, and sovereignty. Her advocacy work is driven by the aspiration to contribute to the restoration of Indigenous Peoples’ inherent connections with their cultures, knowledge, and communities. Notably, Corina played a pivotal role in establishing the Sayaqagvik system of care for children, youth, and families in Northwest Alaska. She served as a co-investigator at Siamit Lab, an innovative academic–tribal Health Partnership affiliated with Harvard Medical School, and held the position of community director for the Della Keats Fellowship, a postgraduate program based in Northwest Alaska supporting the development of the next generation of Indigenous health leaders. Recently, Corina founded Mumik Consulting, dedicated to assisting Indigenous-serving organizations in enhancing their initiatives.

Play the video version below, or scroll down for the podcast version and the transcript.

CONNECTING THE DOTS – PODCAST

Are you a podcast fan? Make sure you subscribe to the podcast version of our Connecting the Dots series here.

ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT

FRANCISCO SOARES (AZIMUTH WORLD FOUNDATION)

Cana, you grew up in Kotzebue and moved to Virginia to pursue your academic work. And Corina, you moved to Kotzebue when you were 18, to work directly with the community there. Can tell us a little bit about your two journeys and how they have led you to your current collaboration?

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

I moved to Kotzebue at 18, just after what would have been high school. And I started working right away at the health organization, doing data coordination. And there began to do 35 years of work with our communities, our youth. I raised kids for 20 years at home, so I was mostly a grassroots volunteer on different community projects, and took little short-term leadership positions throughout the community.

But a few years ago, I worked again at our health organization, in a different role. And began to do academic partnerships in different areas of research. That’s where I got kind of connected.

Sometimes, Cana and I would be in the same webinar without realizing it, because we were in different parts of the country. And then we’d notice that we were both there. And over dinner one day, we just talked about it. And it was astounding how similar our work was, and how it kind of came together in such a beautiful way. So we started thinking about collaborating around that time.

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

Corina and I, we’re sisters. I guess a lot of family members talk about their work in their real life, but our family is really close. We connect as people, and we talk about our kids primarily. We talk about what we’re doing in our lives. So seeing each other in these webinars, and looking at each other in this different way, added a really welcome and wonderful aspect to our relationship as sisters.

I grew up between California and Alaska. I went to college back in the early 90s, and dropped out when I started a family. And I returned home to Kotzebue to have my baby. And then went back to school once my youngest was born. And ever since then, I’ve been really living outside of Kotzebue, though I’m home all the time. But I’ve always felt that it was my duty, with this privilege of an education that I have, to really benefit our People.

When I went to school, I received scholarships from our People. From the Noorvik IRA and from Aqqaluk Trust in Kotzebue. I had a lot of gratitude for that, and I’ve always wanted to give back. That’s how our mom, and our dad Caleb, raised us. To be of service to our People. That’s just a family value that our parents really gave us. Our mom is Gladys I’yiiqpak Pungowiyi, she’s from the Wells family in Noorvik, Alaska. And our biological father, who’s passed away, is Karl Welm, from Germany. But we were also raised and adopted by our stepfather, Caleb Lumen Pungowiyi, who’s Yupik from Savoonga, Alaska.

I just really wanted to give back. And Corina and I, we started seeing each other at these webinars, and we realized our goals were aligned. And I asked her if she would partner with me on some research in the community. And she said no. It took two years to actually get her to finally say yes.

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

She said, “research,” and I turned around and walked away. Research fatigue is real. The cool thing is that as sisters, and as family, we trust each other. And as we began talking, I started to realize that this could actually work. If anybody can make it work, we could make it work, because we do have an extremely high level of communication, and vulnerability and trust between us.

It was also really cool to find out that we’re continuing the legacy of our dad, Caleb Pungowiyi, who was involved in a lot of global and Arctic research, as an Indigenous liaison. And also our mom’s legacy. She was very much an advocate for our People and our needs, as the COO of our Native corporation.

Image Credits: Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

FRANCISCO SOARES

Thank you so much for sharing a little bit of your family history with us. And it’s interesting to see how you’re collaborating now, even if two very different paths led you to do research work.

Reflecting on positionality is crucial for comprehending how to engage with and discuss the communities that are central to your work.

Could you elaborate on your dual roles, one as an academic operating externally to the community, and the other as a community leader working from within? And how do these two roles shape and define your approach?

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

Because I’m not currently living in our region, not even in Alaska, and I haven’t been doing that for a while, it would be pretty audacious of me to try and speak for our communities about their lived realities and community contexts, in my work. Really, my job is to listen to communities, and use my ability, the audience I have, the position I have, to amplify and highlight community voices.

And because of my status as “Dr. Itchuaqiyaq,” academics and others can naturally look at me as some sort of an expert about our People, or a spokesperson for our People, and I try to reject that. I work really hard to pay close attention to issues of power and privileged positionality in my work, and as an Iñupiaq, and to make sure I highlight and amplify community voices, like Corina’s.

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

Cana has always been so generous, often deferring to myself and others in the community, to absolutely make sure that the realistic things in the community are upheld and voiced, which isn’t often done.

And it’s been very helpful for us, I think, to have two people bridging this gap. Because we’re essentially hand-in-hand, bridging a gap between the community and academics.

External Link

Home | Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq

https://www.itchuaqiyaq.com

FRANCISCO SOARES

And speaking of that gap, we know that historically Indigenous communities’ relationship with academia has been marked by instances of exploitation of Indigenous knowledge, by a lack of inclusion of the communities in research work, and by an inability to prioritize community needs in the definition of research goals.

How can we address this history respectfully, avoiding the portrayal of trauma as entertainment? Additionally, how can we ensure an authentic representation of communities that highlights not only their past but also their future aspirations and potential?

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

It’s really, really easy and simple. Just listen to communities. And sadly, that’s a paradigm shift. It’s something that makes people feel really uncomfortable. Especially academics and institutions, they’re used to being in charge and to have the power, and they think that wisdom and innovation come from that area, rather than thinking about the community as the true experts about the community, and their issues, and the land.

In that paradigm shift that I’m talking about – listening to communities – it’s about giving decision-making power in research to communities. That’s how our work is sustainable, because it serves their aspirations, initiatives and needs.

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

As I said earlier, I heard “research” and I turned around the other way. A lot of that comes from this historical disruption that’s happened because of all the Western-structured business and education, and all of these Western ways that came in, and just flip-flopped our priorities, our values. It does not, or did not, accept us as experts.

When we knew we were. We knew we were scientists. I mean, you can’t live in an Arctic community without being an expert in many, many things. Geographically isolated, the most extremes of weather, survival, living off the land – all of those things require every bit of expertise as a Western idea of what you could learn in a book, or practice in a research project. We’ve done practiced it. And we’ve had theories, we’ve practiced them, we made them work, and we are experts.

It’s difficult to think about what I call “flipping the script” with the academic world, or even the Western business-structured world. Even in our community, with our own People. Because of this idea that we’re not experts, or we’re not teachers, or we’re not doctors or scientists.

It took me a while to understand – and we’re still working through it, because it’s a difficult process – that there could be a beautiful, harmonious win-win relationship, if the partnership is done right. Because Indigenous communities have critical needs we can’t afford. And we need to address these needs. Some of them at an expert level, because these are Western-constructed issues that we’re dealing with.

But what if we partnered? What if we partnered, and the academic and research world listened to the communities, and gave the communities authority, and leadership and training? So yes, it could be a beautiful, harmonious win-win. And that’s what we’re working on.

Image Credit: Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

FRANCISCO SOARES

We know that polar research receives generous funding support, for example. But funding can become a space for assimilation practices, too. What is your perspective on current funding trends? And what are their implications for Indigenous scholars and Indigenous communities?

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

We’re all witnessing unprecedented, and really well-intentioned changes in the federal funding sector. And I’m happy to see that. For one, because I think that other funders, even smaller federal funding organizations, should follow suit.

And we also are witnessing an unprecedented Indigenous resurgence. We’re standing up, saying, “We deserve the voice, we have the information, we are the experts.” And it’s just a beautiful thing happening.

Honestly, as an Indigenous community member without formal Western education, it’s nice to be acknowledged at this level, as an expert in my field, and asked to participate. And at the same time, it seems we have a lot of work to do, to make funding support realistically accessible to communities.

I was recently on the NSF “Navigating the New Arctic” panel, to review proposals. And it was extremely difficult for me. At the time, I probably had three full-time positions at an organization that couldn’t fill the positions that were necessary to make things run. And I also have a family, and all these other things going on. And again, we have to live off the land, so there’s subsistence. And to be able to make my brain think in the scientific way, reading these proposals, was extremely difficult.

And thankfully, some really cool people at NSF, like a man named Liam, were willing to meet with me, to kind of debrief my experience on this panel. And my comments were received really well. I also said, “There is no way a community can apply for this and get it. There’s just really no way.” And it was cool to have them listen to that and think, “Maybe there’s a way we can offer something that the communities would be able to get.”

In the private funders area, though, they’ve been way more accessible to communities to be funded. From the ones that I’ve seen, a lot of them are capital projects. And the social needs that we have require workers. They require people that you hire, rather than a thing that you can buy. So that’s another adjustment I think that private funders need to make. It would be really helpful to be able to fund these other types of projects, like traditional and cultural education, that don’t necessarily need a bunch of capital.

In my opinion though, I haven’t seen as big of a push from private funders, when it comes to changing their internal measures, and to address colonial Western assumptions about how funding should work.

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

I guess in changing those policies that Corina talked about – colonial practices that don’t necessarily work well, or mesh well, or translate well to community realities and value systems – those changes that are necessary, are much more easily done by private funders, than in the federal sector.

Philanthropic funders can hear from communities that, for example, their reporting policies are causing issues. Or that things like “SMART” goals are leaving out community realities, such as their value systems. Also, regarding how time works, and the realities and constraints related to how timing happens, in Indigenous communities.

But like Corina was saying, federal funding is really shifting, in what I agree is a well-intentioned way. In my opinion, the National Science Foundation, their office of Polar Programs, is where it’s at right now, when it comes to modelling equity. And they’re doing cool work, really, in meeting Indigenous community concerns.

But I also agree with Corina, when it comes to the way these concerns are really being incorporated into federal funding policies and realities. Yes, they want to have more Indigenous participation in research. But could a fully Indigenous organizational proposal be competitive in the federal funding space? Maybe not.

That takes a big shift in who reviews proposals, which is academia. Academia likes to reify academia as the expert. It’s a kind of circle. And at National Science Foundation, and other organizations in the federal space, there’s a lot of work to change those policies.

There are good intentions in what they’re trying to do. But what happens is kind of clumsy also, when it comes to Indigenous communities. Because oftentimes they use a pan-Indigenous approach. And the differences in how Indigenous communities function and work in the lower 48 versus Alaska, for example, are very, very different. But federal policies that are literally rolling out right now in response to executive orders, and different things like that, don’t really account for those nuances very well.

Image Credits: Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

FRANCISCO SOARES

You’ve been collaborating on the “Rematriation Project – Restoring and Sharing Inuit Knowledges.”

Can you tell us about this project and how it aims to revitalize community knowledge, while avoiding data extractivism? And do you believe that new digital communication devices and platforms have the potential to foster self-determination within Indigenous communities?

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

The Rematriation Project is a collaboration between Corina over at Mumik Consulting, and Virginia Tech. I’m the the lead here, at Virginia Tech. And we’re working together to create an online community archive that serves the People of Northwest Alaska. When I say “serves”, I mean that for real.

We’re working to develop structures that support an Inuit archive that was designed for Inuit users, versus academic users. And we’re also working to grow local capacities in digital archiving itself, so that this community archive is replicable and it’s also truly the communities’ project. Because we want to make sure the project is sustainable, that the academic partnership part can fade away, and the community is able to really keep this moving, and grow towards community needs. We’re just helping to get it started.

We aim to grow those capacities in digital archiving. And also to spark interest and growth in the community, with these associated skills. That includes data literacy, which is really important in protecting Indigenous data, and also in supporting Indigenous data sovereignty. Data literacy could be as simple as using the archive to collect data into a spread sheet, and then using that spreadsheet to help make decisions and community members’ rules. But also just to learn about cool stuff, to spark curiosity within our youth and in our community. To spark community pride in our cultural heritage, which would be preserved in this digital community archive.

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

We purposefully went and started off with the communities’ need. I was sitting over this rural archive of our oral history. And it was 2300 files of story upon story. Of our history, our knowledge, geographical things. And subsistence knowledge: how to make tools, how to make a seal scratcher for the ice, so that the seal doesn’t think it’s a polar bear, rather than a buddy seal.

Those types of things are in there, and we can’t even imagine. We don’t even know, because they were all in Iñupiaq language. And so the younger generations cannot understand them. We don’t know our language fluently. And our elders who still hold the language, they’re older, they’re retired, they don’t have the physical ability anymore to sit and help us archive. And we don’t have the finances to hire people to do all these things.

And so I told Cana, “Here’s the situation. This is something that our People really, really need. We need to get back to our culture, to our language, our ways. This could help so many things that our communities are suffering from.” And Cana started to think about what she can offer, and the people that she works with, three doors down.

She was able to find us a team. And using her background and her expertise in technical communication and rhetoric, she was be able to translate back and forth between the technicalities that we don’t really understand. So that’s kind of how we started off with the Rematriation Project.

And it’s grown now to another project called the Coding Project, which is helping us code the Iñupiaq language, training the computer to actually translate for us. And that was the magic of “Dr. Itchuaqiyaq”, and her networking skills over yonder: setting us up with world renowned computational linguists, and really helping to put those things forward.

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

And that’s the key. In hearing the communities’ needs, you hear the community where they’re at. Because academics is a little bit siloed. We try to do interdisciplinary work, but it’s still decently siloed and project-based.

And we try to think about the problem that the community is posing, and translate it into complementary projects. And we try to understand the skills necessary to get those projects going, and to use persuasion to attract these experts, so that they basically work for free on these projects for the community.

I’m not a digital archivist. I’m not a computational linguist. I’m a technical communicator. And what I do is use communication strategies to help people do their jobs, and to work together to meet community needs, goals and aspirations.

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

The community is engaged when you can see equity, justice, resurgence and sovereignty being upheld, and when they’re being a part of doing that. Because there’s a heart behind it now. It’s not just a scientific or academic project. It’s something that is actually going to be helping the community.

And we purposefully didn’t go for big grants in the beginning, because we wanted to do it our own way. And we wanted to maintain this purity of doing it in a way that actually works, and where we don’t have to check-mark the criteria for the grant, where we’re not making sure that we’re complying with the grant. Because when you do that, then you skew your project to the grant, rather than just maintaining the purity of what you really need to do, to help the People.

Image Credits: Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

FRANCISCO SOARES

Your work together strongly advocates that Indigenous communities must be given an equal chance to weigh in on what research is done on their Indigenous land. It also stresses the need to conduct research according to the communities’ needs, values and knowledge systems.

Are there still many gaps between intentions to carry out equitable research and the way research projects are actually being designed and implemented on the ground?

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

Of course. There were layers and layers of jumbled up issues created by colonialism over the last century. For many, many Indigenous People and communities there’s a lot to work through. And I feel like we’re now just realizing that this needs to happen.

And as a community member whose eyes have opened, I can see things like structural racism, and psychological oppression, and all of these things. I can see it now that I know. And it’s very difficult for me, as a community member, to even bring these topics up, to a place where even our organizations, or even the People, are realizing it themselves, or admitting it, or taking responsibility for, all of those things.

So even at the community level, there’s so much work to be done.

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

I wound up writing this Equitable Arctic Research guide, and self-publishing it. It’s just a 12-page guide – I actually got it peer-reviewed by colleagues and Indigenous community members, just to make sure what I’m saying is not out there – outlining 10 strategies towards Equitable Arctic Research.

And I wasn’t quite sure where that was going, but what resulted is having a newsletter, and then Corina joining the newsletter. We started that getting close to March 2023. And since then, we’ve still been doing our community-engaged research, and we’ve been riding together as an academic and community partnership, and really going through the paces, and applying for NSF granting, and seeking philanthropic grants, and doing all these things to support these projects that we were just describing. And feeling the growing pains of that. Feeling what that really was like.

And Corina was saying that our relationship supports that work quite a bit, because no matter what, Corina and I love each other. We’re sisters. Corina used to carry me on her back, I was her baby. We know we have that background with each other. And we have fought each other. We’ve gotten in fights in this capacity, and worked really hard to resolve them. Because we could trust each other, even though we were angry at the time, or didn’t agree. We were able to rely on that relationship that we have, to tease out what’s really going on here, and have really vulnerable conversations. Even cry to each other, about what’s really going on in our professional work, and how that’s impacting both of us. And then, after we’ve experienced those hiccups, being able to zoom out and look at how this is actually a symptom of something bigger than just her and I’s interaction, but really thinking about how that’s an interaction between institutions and communities.

And so over that time of really working hard together, and working on deep listening to each other, and really combining all our experience that we’ve had, we wound up developing a course that just launched, the Effective Community Engagement and Equitable Arctic Research course.

We get tons of emails and questions about how things specifically work. And so it’s been fun to really think about showing somebody how to at least get started in this way. Even if they are a seasoned scholar. Or a graduate student just trying to start off well. Or someone working within their own power structures in academia, as somebody with less power in the structure: how they can still use their institutional power and positionality to work towards equitable outcomes and equitable engagement with Indigenous communities, in the Arctic especially.

FRANCISCO SOARES

Congratulations on launching the course!

You were just describing how the trust between you is what allowed you to look at these problems between communities and institutions more deeply.

Trust has been missing in the relationship between academia and Indigenous communities for a long time. Can you elaborate on the respectful processes involved in truly understanding the communities’ needs? What is involved in rebuilding trust with Indigenous communities in Alaska, both in research and institutional settings?

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

I work with Harvard Medical, helping to train doctors. And one of my first things is, “How much school, how many books did you have to read, how much did you have to learn about medicine, to get to where you are today? Well, you need to read and learn about us, as a People.”

I think that what needs to happen is really try to find out and understand the people that you’re working with. Their value systems, the local dynamics of the village on the ground, of how things work. Understanding that Summer time and Fall time are not a great time to come, because we’re subsisting. We have to survive the rest of the year. So don’t come knocking on our door during that time, unless you’re ready to grab an ulu and help us cut fish. And that brings it to another level of relationship.

We’re relational people. Indigenous Peoples are relational and communal people. We help each other. We’re not these siloed families in white picket fences that drive into a garage and barely wave at your neighbor. We know each other, we help each other, we live together. And that should include anyone coming from the outside to live with us. We’re relational people, and we can’t keep these separations. I don’t want to know that you’re a doctor of whatever it is. I want to know where you’re from. I want to know if you have siblings, or if you have children, or what your dog’s name is, or what kind of fishing you like to do. That matters to us before anything else.

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

The relationships are super important. And the only way to build those relationships is to recognize that you’re coming into a community as a person, like Corina was saying. And that you’re engaging with the community as people, as well. And not being just your job description, or your CV, because they’re not compelling.

And then those relationships are really important in helping you to really listen to communities. Because then you are connecting as people, and building your own trust for the community, when you listen to them. And they’re building trust in you, when you listen. It’s this mutual trust.

In these two academic teams that I work in, which are really interdisciplinary and filled with early career scholars, most of us don’t have tenure yet. So we are in this place of proving ourselves to our own employer, that we should keep our job, and that involves all sorts of requirements. So they have to trust the community, and trust that this project is really going to help them maintain and grow their own career. As much as the community is like, “This project is going to help us maintain and grow our aspirations and needs.” And in order for that to happen, everybody is stretching themselves to work towards our goals, with all our skills combined. We are coming together as a team.

And so I had to look at my own skill set with an open mind, and think about how it pairs with the communities’ goals, aspirations and needs. And that really takes a lot of humility work. And that’s not easy, but it’s really needed.

Image Credits: Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

FRANCISCO SOARES

More and more people are talking about Indigenous knowledge these days. But at the same time, we still see an underrepresentation of Indigenous students. Cana, can you tell us more about the ways in which your work attempts to bridge this gap?

And a parallel question to Corina: Based on your involvement with youth leadership programs, can you tell us more about the centrality of lifting people back into leadership?

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

I went through my PhD, and I decided I didn’t want to be a professor. Because there’s just a lot of things that I find toxic here. And the very things that I found toxic here as a student, are some of the barriers of access that Inuit students, and other Indigenous students, and students from marginalized and underrepresented communities, face in academia.

I faced those myself, and I thought, “Thanks for the doctorate. I hope I get a better pay because of it, but I’m gone.” But I had these universities offering me jobs, and my mom basically sat me down, and was like, “Look at the resources that you have access to. You have basically a six-year contract with these folks, as a tenure track professor. How about you reframe academia in your mind as a challenge to pour academia’s resources right back at our People? Just direct those resources towards our People.” And that to me seemed like a great goal.

And I love teaching, it turns out. And I love research, it turns out. But the reality is I love my People more. And the work that I choose to do as a scholar is to find ways to meet our People’s needs, through using university resources, but also through understanding how academia works. And working in my sphere of influence to change my department, to change fellowship programs that I’m involved with. To create pathways towards this school, if people choose it. To give them the support that they need. To create a way that this isn’t such a harsh place.

I work hard to hold space for people in my community to get involved in research, or just to get involved in academic practices at all. And just to demystify it. And then also just to create a path for Inuit students to follow. Because I had to kind of make that path myself, and I know how hard it can be.

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

And I myself, I don’t desire to get a degree. I never did.

I remember having a conversation with our team in the health organization. We were talking about elevating the voices of the local people, and getting a seat at the table of decision-making. And one of the psychologists was saying, “Well, we just need to encourage them to go to school, and get educated, and then they’ll have a sit at the table, and be able to put their voice in.” And I said, “No.” And this was someone who was absolutely amazing, equity-minded, all of that.

But that was what they really believed, because that’s what we’ve been trained to believe. We’ve always been told in the village, “Go out, get your education, come back and help your People.” That’s the thing. And for me, I never desired it. And I’m not going to be thought less than, because of that. I am educated. I’m self-educated, and I’m community-educated.

I got my GED, but many of our People only went to high school. Many of them were sent to boarding schools, and didn’t go any further than that. But they are expert sled-makers, or they know about going out in the country, and what kind of weather with this cloud in the sky means, and why you shouldn’t go there to the yellow cloud in the sky because it’s open water.

So as I help to develop youth programs and raising up leadership, I always want to make sure that it’s the wisdom of our People that is considered education. We have our own educational system in the village. We always have. But it’s more of an apprenticeship model of education in degrees, that you graduate. You graduate to be able to cut the fish at a certain age. And I’ve been present when an 11 year-old is going, “I can’t believe it. This year is my year.”

There’s this level of wisdom that happens in a whole different system, in a whole different way, and that is equal to a Western education system. That needs to be acknowledged in every respect.

Image Credits: Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

FRANCISCO SOARES

In what ways would you like to see your work being implemented by others in the coming years? And what is making you hopeful about the future?

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

Liam at NSF – a wonderful man, who has been a real champion for Indigenous work and research – he asked a similar question to me, at our first meeting together. He said, “What do you hope from all of this?” I think that we can be a voice to change the systems that affect our People globally. We can be a part of that change. And for some reason, we have this sort of magic, that really works in that respect, between the different communities, whether it’s the Indigenous communities or the academic communities.

We’re able to do that, and we see that there’s a bigger reach and a bigger need, globally. And there are many of us, Indigenous People, that are doing this very same thing. And so I just want to be a part of that community. And I want to help change things for our homes, which have many needs, needs that aren’t necessarily considered in research and academia.

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

And for me, I want to help through the work that I do on the academic side, and how I translate this experience into publications, which are then used as tools by other people, to justify whatever change they are advocating for in their own work.

What would be success for me, is that I can retire from this gig of like, “Can we just do some equity, please?” Our dad was doing this in the early 90s. It’s been a long time that we’re asking the same thing.

And Corina and I, a lot of our recommendations are just, to us, really common sense. And so I would love it if people would engage in doing the work. And checking their motivations. And realizing that power-sharing is actually the key to this innovation in Arctic research. Sharing power, and hearing about “the yellow cloud in the sky means open water,” and recognizing that as a scientific observation and a demonstration of scientific expertise.

And when someone says, “Hey, we’re interested in XYZ.” And the community is like, “Yes, we already kind of know what’s happening with that. It’s probably something about this.” To listen to them. Because what they’re going to say next is, “What we’re really interested in is this. Because this is something that’s coming. It’s creeping up, and we haven’t figured out what’s coming towards us.” Because in Kotzebue, in the Northwest Arctic area, and along this coast in Alaska, these frontline communities are facing climate change right now. And so academic curiosities aren’t saving homes, aren’t saving lives, aren’t saving cultural connection and community connection to the land. It’s not doing that work.

And so my goal is for people just to listen. To do the work. To get out of their own way, really, towards innovation and working with communities. Get out of your own way, so I can retire and do construction. Which is really what I want to do, build little houses and furniture, play in my workshop and wear an apron, and not worry about “Dr. So-and-so” acting messy at home. So please, that would make me happy.

External Link

Connecting the Dots with Dr. Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

With our two guests, sisters and collaborators spearheading the Respectful Research intiative, we explore a decolonizing approach to Arctic research.

In a recent episode of our podcast, we had an enlightening conversation with Iñupiaq Conservation Biologist Dr. Victoria Buschman about the role of Arctic Indigenous communities in shaping conservation strategies.

Today, we are expanding upon our previous discussion to more deeply explore a decolonizing approach to Arctic research in general. Furthermore, we aim to examine how this approach can be applied within institutional settings at the community level. We are privileged to have not just one, but two highly knowledgeable guests joining us for this episode: Dr. Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer, who are not only sisters but also collaborators currently spearheading the groundbreaking Respectful Research intiative.

Dr. Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq is assistant professor of technical and scientific communication at Virginia Tech. Cana is Iñupiaq, from Northwest Alaska and an enrolled member of the Noorvik Native Community. The digital humanities, data analysis, critical race theory, and Indigenous knowledges are combined in Cana’s research, in order to investigate the intersections of identity, science/technology/medicine, colonialism, and culture. Their work sheds light on how the marginalization of underrepresented scholars and communities is often perpetuated in mainstream academic, institutional, and societal practice. Using theory and data, they aim to craft methodologies that empower others to undertake research and engage in social justice work with respect and sensitivity, particularly in the realm of technical communication and other disciplines.

Corina Qaaġraq Kramer, also of Iñupiaq descent, hails from the Native Village of Kotzebue. As a community leader with extensive frontline experience, Corina brings a unique expertise to her work, specializing in bridging traditional Indigenous knowledge and values with Western institutional practices to enhance the well-being of Native communities, health, and sovereignty. Her advocacy work is driven by the aspiration to contribute to the restoration of Indigenous Peoples’ inherent connections with their cultures, knowledge, and communities. Notably, Corina played a pivotal role in establishing the Sayaqagvik system of care for children, youth, and families in Northwest Alaska. She served as a co-investigator at Siamit Lab, an innovative academic–tribal Health Partnership affiliated with Harvard Medical School, and held the position of community director for the Della Keats Fellowship, a postgraduate program based in Northwest Alaska supporting the development of the next generation of Indigenous health leaders. Recently, Corina founded Mumik Consulting, dedicated to assisting Indigenous-serving organizations in enhancing their initiatives.

Play the video version below, or scroll down for the podcast version and the transcript.

CONNECTING THE DOTS – PODCAST

Are you a podcast fan? Make sure you subscribe to the podcast version of our Connecting the Dots series here.

ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT

FRANCISCO SOARES (AZIMUTH WORLD FOUNDATION)

Cana, you grew up in Kotzebue and moved to Virginia to pursue your academic work. And Corina, you moved to Kotzebue when you were 18, to work directly with the community there. Can tell us a little bit about your two journeys and how they have led you to your current collaboration?

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

I moved to Kotzebue at 18, just after what would have been high school. And I started working right away at the health organization, doing data coordination. And there began to do 35 years of work with our communities, our youth. I raised kids for 20 years at home, so I was mostly a grassroots volunteer on different community projects, and took little short-term leadership positions throughout the community.

But a few years ago, I worked again at our health organization, in a different role. And began to do academic partnerships in different areas of research. That’s where I got kind of connected.

Sometimes, Cana and I would be in the same webinar without realizing it, because we were in different parts of the country. And then we’d notice that we were both there. And over dinner one day, we just talked about it. And it was astounding how similar our work was, and how it kind of came together in such a beautiful way. So we started thinking about collaborating around that time.

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

Corina and I, we’re sisters. I guess a lot of family members talk about their work in their real life, but our family is really close. We connect as people, and we talk about our kids primarily. We talk about what we’re doing in our lives. So seeing each other in these webinars, and looking at each other in this different way, added a really welcome and wonderful aspect to our relationship as sisters.

I grew up between California and Alaska. I went to college back in the early 90s, and dropped out when I started a family. And I returned home to Kotzebue to have my baby. And then went back to school once my youngest was born. And ever since then, I’ve been really living outside of Kotzebue, though I’m home all the time. But I’ve always felt that it was my duty, with this privilege of an education that I have, to really benefit our People.

When I went to school, I received scholarships from our People. From the Noorvik IRA and from Aqqaluk Trust in Kotzebue. I had a lot of gratitude for that, and I’ve always wanted to give back. That’s how our mom, and our dad Caleb, raised us. To be of service to our People. That’s just a family value that our parents really gave us. Our mom is Gladys I’yiiqpak Pungowiyi, she’s from the Wells family in Noorvik, Alaska. And our biological father, who’s passed away, is Karl Welm, from Germany. But we were also raised and adopted by our stepfather, Caleb Lumen Pungowiyi, who’s Yupik from Savoonga, Alaska.

I just really wanted to give back. And Corina and I, we started seeing each other at these webinars, and we realized our goals were aligned. And I asked her if she would partner with me on some research in the community. And she said no. It took two years to actually get her to finally say yes.

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

She said, “research,” and I turned around and walked away. Research fatigue is real. The cool thing is that as sisters, and as family, we trust each other. And as we began talking, I started to realize that this could actually work. If anybody can make it work, we could make it work, because we do have an extremely high level of communication, and vulnerability and trust between us.

It was also really cool to find out that we’re continuing the legacy of our dad, Caleb Pungowiyi, who was involved in a lot of global and Arctic research, as an Indigenous liaison. And also our mom’s legacy. She was very much an advocate for our People and our needs, as the COO of our Native corporation.

Image Credits: Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

FRANCISCO SOARES

Thank you so much for sharing a little bit of your family history with us. And it’s interesting to see how you’re collaborating now, even if two very different paths led you to do research work.

Reflecting on positionality is crucial for comprehending how to engage with and discuss the communities that are central to your work.

Could you elaborate on your dual roles, one as an academic operating externally to the community, and the other as a community leader working from within? And how do these two roles shape and define your approach?

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

Because I’m not currently living in our region, not even in Alaska, and I haven’t been doing that for a while, it would be pretty audacious of me to try and speak for our communities about their lived realities and community contexts, in my work. Really, my job is to listen to communities, and use my ability, the audience I have, the position I have, to amplify and highlight community voices.

And because of my status as “Dr. Itchuaqiyaq,” academics and others can naturally look at me as some sort of an expert about our People, or a spokesperson for our People, and I try to reject that. I work really hard to pay close attention to issues of power and privileged positionality in my work, and as an Iñupiaq, and to make sure I highlight and amplify community voices, like Corina’s.

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

Cana has always been so generous, often deferring to myself and others in the community, to absolutely make sure that the realistic things in the community are upheld and voiced, which isn’t often done.

And it’s been very helpful for us, I think, to have two people bridging this gap. Because we’re essentially hand-in-hand, bridging a gap between the community and academics.

External Link

Home | Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq

https://www.itchuaqiyaq.com

FRANCISCO SOARES

And speaking of that gap, we know that historically Indigenous communities’ relationship with academia has been marked by instances of exploitation of Indigenous knowledge, by a lack of inclusion of the communities in research work, and by an inability to prioritize community needs in the definition of research goals.

How can we address this history respectfully, avoiding the portrayal of trauma as entertainment? Additionally, how can we ensure an authentic representation of communities that highlights not only their past but also their future aspirations and potential?

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

It’s really, really easy and simple. Just listen to communities. And sadly, that’s a paradigm shift. It’s something that makes people feel really uncomfortable. Especially academics and institutions, they’re used to being in charge and to have the power, and they think that wisdom and innovation come from that area, rather than thinking about the community as the true experts about the community, and their issues, and the land.

In that paradigm shift that I’m talking about – listening to communities – it’s about giving decision-making power in research to communities. That’s how our work is sustainable, because it serves their aspirations, initiatives and needs.

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

As I said earlier, I heard “research” and I turned around the other way. A lot of that comes from this historical disruption that’s happened because of all the Western-structured business and education, and all of these Western ways that came in, and just flip-flopped our priorities, our values. It does not, or did not, accept us as experts.

When we knew we were. We knew we were scientists. I mean, you can’t live in an Arctic community without being an expert in many, many things. Geographically isolated, the most extremes of weather, survival, living off the land – all of those things require every bit of expertise as a Western idea of what you could learn in a book, or practice in a research project. We’ve done practiced it. And we’ve had theories, we’ve practiced them, we made them work, and we are experts.

It’s difficult to think about what I call “flipping the script” with the academic world, or even the Western business-structured world. Even in our community, with our own People. Because of this idea that we’re not experts, or we’re not teachers, or we’re not doctors or scientists.

It took me a while to understand – and we’re still working through it, because it’s a difficult process – that there could be a beautiful, harmonious win-win relationship, if the partnership is done right. Because Indigenous communities have critical needs we can’t afford. And we need to address these needs. Some of them at an expert level, because these are Western-constructed issues that we’re dealing with.

But what if we partnered? What if we partnered, and the academic and research world listened to the communities, and gave the communities authority, and leadership and training? So yes, it could be a beautiful, harmonious win-win. And that’s what we’re working on.

Image Credit: Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

FRANCISCO SOARES

We know that polar research receives generous funding support, for example. But funding can become a space for assimilation practices, too. What is your perspective on current funding trends? And what are their implications for Indigenous scholars and Indigenous communities?

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

We’re all witnessing unprecedented, and really well-intentioned changes in the federal funding sector. And I’m happy to see that. For one, because I think that other funders, even smaller federal funding organizations, should follow suit.

And we also are witnessing an unprecedented Indigenous resurgence. We’re standing up, saying, “We deserve the voice, we have the information, we are the experts.” And it’s just a beautiful thing happening.

Honestly, as an Indigenous community member without formal Western education, it’s nice to be acknowledged at this level, as an expert in my field, and asked to participate. And at the same time, it seems we have a lot of work to do, to make funding support realistically accessible to communities.

I was recently on the NSF “Navigating the New Arctic” panel, to review proposals. And it was extremely difficult for me. At the time, I probably had three full-time positions at an organization that couldn’t fill the positions that were necessary to make things run. And I also have a family, and all these other things going on. And again, we have to live off the land, so there’s subsistence. And to be able to make my brain think in the scientific way, reading these proposals, was extremely difficult.

And thankfully, some really cool people at NSF, like a man named Liam, were willing to meet with me, to kind of debrief my experience on this panel. And my comments were received really well. I also said, “There is no way a community can apply for this and get it. There’s just really no way.” And it was cool to have them listen to that and think, “Maybe there’s a way we can offer something that the communities would be able to get.”

In the private funders area, though, they’ve been way more accessible to communities to be funded. From the ones that I’ve seen, a lot of them are capital projects. And the social needs that we have require workers. They require people that you hire, rather than a thing that you can buy. So that’s another adjustment I think that private funders need to make. It would be really helpful to be able to fund these other types of projects, like traditional and cultural education, that don’t necessarily need a bunch of capital.

In my opinion though, I haven’t seen as big of a push from private funders, when it comes to changing their internal measures, and to address colonial Western assumptions about how funding should work.

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

I guess in changing those policies that Corina talked about – colonial practices that don’t necessarily work well, or mesh well, or translate well to community realities and value systems – those changes that are necessary, are much more easily done by private funders, than in the federal sector.

Philanthropic funders can hear from communities that, for example, their reporting policies are causing issues. Or that things like “SMART” goals are leaving out community realities, such as their value systems. Also, regarding how time works, and the realities and constraints related to how timing happens, in Indigenous communities.

But like Corina was saying, federal funding is really shifting, in what I agree is a well-intentioned way. In my opinion, the National Science Foundation, their office of Polar Programs, is where it’s at right now, when it comes to modelling equity. And they’re doing cool work, really, in meeting Indigenous community concerns.

But I also agree with Corina, when it comes to the way these concerns are really being incorporated into federal funding policies and realities. Yes, they want to have more Indigenous participation in research. But could a fully Indigenous organizational proposal be competitive in the federal funding space? Maybe not.

That takes a big shift in who reviews proposals, which is academia. Academia likes to reify academia as the expert. It’s a kind of circle. And at National Science Foundation, and other organizations in the federal space, there’s a lot of work to change those policies.

There are good intentions in what they’re trying to do. But what happens is kind of clumsy also, when it comes to Indigenous communities. Because oftentimes they use a pan-Indigenous approach. And the differences in how Indigenous communities function and work in the lower 48 versus Alaska, for example, are very, very different. But federal policies that are literally rolling out right now in response to executive orders, and different things like that, don’t really account for those nuances very well.

Image Credits: Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

FRANCISCO SOARES

You’ve been collaborating on the “Rematriation Project – Restoring and Sharing Inuit Knowledges.”

Can you tell us about this project and how it aims to revitalize community knowledge, while avoiding data extractivism? And do you believe that new digital communication devices and platforms have the potential to foster self-determination within Indigenous communities?

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

The Rematriation Project is a collaboration between Corina over at Mumik Consulting, and Virginia Tech. I’m the the lead here, at Virginia Tech. And we’re working together to create an online community archive that serves the People of Northwest Alaska. When I say “serves”, I mean that for real.

We’re working to develop structures that support an Inuit archive that was designed for Inuit users, versus academic users. And we’re also working to grow local capacities in digital archiving itself, so that this community archive is replicable and it’s also truly the communities’ project. Because we want to make sure the project is sustainable, that the academic partnership part can fade away, and the community is able to really keep this moving, and grow towards community needs. We’re just helping to get it started.

We aim to grow those capacities in digital archiving. And also to spark interest and growth in the community, with these associated skills. That includes data literacy, which is really important in protecting Indigenous data, and also in supporting Indigenous data sovereignty. Data literacy could be as simple as using the archive to collect data into a spread sheet, and then using that spreadsheet to help make decisions and community members’ rules. But also just to learn about cool stuff, to spark curiosity within our youth and in our community. To spark community pride in our cultural heritage, which would be preserved in this digital community archive.

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

We purposefully went and started off with the communities’ need. I was sitting over this rural archive of our oral history. And it was 2300 files of story upon story. Of our history, our knowledge, geographical things. And subsistence knowledge: how to make tools, how to make a seal scratcher for the ice, so that the seal doesn’t think it’s a polar bear, rather than a buddy seal.

Those types of things are in there, and we can’t even imagine. We don’t even know, because they were all in Iñupiaq language. And so the younger generations cannot understand them. We don’t know our language fluently. And our elders who still hold the language, they’re older, they’re retired, they don’t have the physical ability anymore to sit and help us archive. And we don’t have the finances to hire people to do all these things.

And so I told Cana, “Here’s the situation. This is something that our People really, really need. We need to get back to our culture, to our language, our ways. This could help so many things that our communities are suffering from.” And Cana started to think about what she can offer, and the people that she works with, three doors down.

She was able to find us a team. And using her background and her expertise in technical communication and rhetoric, she was be able to translate back and forth between the technicalities that we don’t really understand. So that’s kind of how we started off with the Rematriation Project.

And it’s grown now to another project called the Coding Project, which is helping us code the Iñupiaq language, training the computer to actually translate for us. And that was the magic of “Dr. Itchuaqiyaq”, and her networking skills over yonder: setting us up with world renowned computational linguists, and really helping to put those things forward.

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

And that’s the key. In hearing the communities’ needs, you hear the community where they’re at. Because academics is a little bit siloed. We try to do interdisciplinary work, but it’s still decently siloed and project-based.

And we try to think about the problem that the community is posing, and translate it into complementary projects. And we try to understand the skills necessary to get those projects going, and to use persuasion to attract these experts, so that they basically work for free on these projects for the community.

I’m not a digital archivist. I’m not a computational linguist. I’m a technical communicator. And what I do is use communication strategies to help people do their jobs, and to work together to meet community needs, goals and aspirations.

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

The community is engaged when you can see equity, justice, resurgence and sovereignty being upheld, and when they’re being a part of doing that. Because there’s a heart behind it now. It’s not just a scientific or academic project. It’s something that is actually going to be helping the community.

And we purposefully didn’t go for big grants in the beginning, because we wanted to do it our own way. And we wanted to maintain this purity of doing it in a way that actually works, and where we don’t have to check-mark the criteria for the grant, where we’re not making sure that we’re complying with the grant. Because when you do that, then you skew your project to the grant, rather than just maintaining the purity of what you really need to do, to help the People.

Image Credits: Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

FRANCISCO SOARES

Your work together strongly advocates that Indigenous communities must be given an equal chance to weigh in on what research is done on their Indigenous land. It also stresses the need to conduct research according to the communities’ needs, values and knowledge systems.

Are there still many gaps between intentions to carry out equitable research and the way research projects are actually being designed and implemented on the ground?

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

Of course. There were layers and layers of jumbled up issues created by colonialism over the last century. For many, many Indigenous People and communities there’s a lot to work through. And I feel like we’re now just realizing that this needs to happen.

And as a community member whose eyes have opened, I can see things like structural racism, and psychological oppression, and all of these things. I can see it now that I know. And it’s very difficult for me, as a community member, to even bring these topics up, to a place where even our organizations, or even the People, are realizing it themselves, or admitting it, or taking responsibility for, all of those things.

So even at the community level, there’s so much work to be done.

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

I wound up writing this Equitable Arctic Research guide, and self-publishing it. It’s just a 12-page guide – I actually got it peer-reviewed by colleagues and Indigenous community members, just to make sure what I’m saying is not out there – outlining 10 strategies towards Equitable Arctic Research.

And I wasn’t quite sure where that was going, but what resulted is having a newsletter, and then Corina joining the newsletter. We started that getting close to March 2023. And since then, we’ve still been doing our community-engaged research, and we’ve been riding together as an academic and community partnership, and really going through the paces, and applying for NSF granting, and seeking philanthropic grants, and doing all these things to support these projects that we were just describing. And feeling the growing pains of that. Feeling what that really was like.

And Corina was saying that our relationship supports that work quite a bit, because no matter what, Corina and I love each other. We’re sisters. Corina used to carry me on her back, I was her baby. We know we have that background with each other. And we have fought each other. We’ve gotten in fights in this capacity, and worked really hard to resolve them. Because we could trust each other, even though we were angry at the time, or didn’t agree. We were able to rely on that relationship that we have, to tease out what’s really going on here, and have really vulnerable conversations. Even cry to each other, about what’s really going on in our professional work, and how that’s impacting both of us. And then, after we’ve experienced those hiccups, being able to zoom out and look at how this is actually a symptom of something bigger than just her and I’s interaction, but really thinking about how that’s an interaction between institutions and communities.

And so over that time of really working hard together, and working on deep listening to each other, and really combining all our experience that we’ve had, we wound up developing a course that just launched, the Effective Community Engagement and Equitable Arctic Research course.

We get tons of emails and questions about how things specifically work. And so it’s been fun to really think about showing somebody how to at least get started in this way. Even if they are a seasoned scholar. Or a graduate student just trying to start off well. Or someone working within their own power structures in academia, as somebody with less power in the structure: how they can still use their institutional power and positionality to work towards equitable outcomes and equitable engagement with Indigenous communities, in the Arctic especially.

FRANCISCO SOARES

Congratulations on launching the course!

You were just describing how the trust between you is what allowed you to look at these problems between communities and institutions more deeply.

Trust has been missing in the relationship between academia and Indigenous communities for a long time. Can you elaborate on the respectful processes involved in truly understanding the communities’ needs? What is involved in rebuilding trust with Indigenous communities in Alaska, both in research and institutional settings?

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

I work with Harvard Medical, helping to train doctors. And one of my first things is, “How much school, how many books did you have to read, how much did you have to learn about medicine, to get to where you are today? Well, you need to read and learn about us, as a People.”

I think that what needs to happen is really try to find out and understand the people that you’re working with. Their value systems, the local dynamics of the village on the ground, of how things work. Understanding that Summer time and Fall time are not a great time to come, because we’re subsisting. We have to survive the rest of the year. So don’t come knocking on our door during that time, unless you’re ready to grab an ulu and help us cut fish. And that brings it to another level of relationship.

We’re relational people. Indigenous Peoples are relational and communal people. We help each other. We’re not these siloed families in white picket fences that drive into a garage and barely wave at your neighbor. We know each other, we help each other, we live together. And that should include anyone coming from the outside to live with us. We’re relational people, and we can’t keep these separations. I don’t want to know that you’re a doctor of whatever it is. I want to know where you’re from. I want to know if you have siblings, or if you have children, or what your dog’s name is, or what kind of fishing you like to do. That matters to us before anything else.

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

The relationships are super important. And the only way to build those relationships is to recognize that you’re coming into a community as a person, like Corina was saying. And that you’re engaging with the community as people, as well. And not being just your job description, or your CV, because they’re not compelling.

And then those relationships are really important in helping you to really listen to communities. Because then you are connecting as people, and building your own trust for the community, when you listen to them. And they’re building trust in you, when you listen. It’s this mutual trust.

In these two academic teams that I work in, which are really interdisciplinary and filled with early career scholars, most of us don’t have tenure yet. So we are in this place of proving ourselves to our own employer, that we should keep our job, and that involves all sorts of requirements. So they have to trust the community, and trust that this project is really going to help them maintain and grow their own career. As much as the community is like, “This project is going to help us maintain and grow our aspirations and needs.” And in order for that to happen, everybody is stretching themselves to work towards our goals, with all our skills combined. We are coming together as a team.

And so I had to look at my own skill set with an open mind, and think about how it pairs with the communities’ goals, aspirations and needs. And that really takes a lot of humility work. And that’s not easy, but it’s really needed.

Image Credits: Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

FRANCISCO SOARES

More and more people are talking about Indigenous knowledge these days. But at the same time, we still see an underrepresentation of Indigenous students. Cana, can you tell us more about the ways in which your work attempts to bridge this gap?

And a parallel question to Corina: Based on your involvement with youth leadership programs, can you tell us more about the centrality of lifting people back into leadership?

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

I went through my PhD, and I decided I didn’t want to be a professor. Because there’s just a lot of things that I find toxic here. And the very things that I found toxic here as a student, are some of the barriers of access that Inuit students, and other Indigenous students, and students from marginalized and underrepresented communities, face in academia.

I faced those myself, and I thought, “Thanks for the doctorate. I hope I get a better pay because of it, but I’m gone.” But I had these universities offering me jobs, and my mom basically sat me down, and was like, “Look at the resources that you have access to. You have basically a six-year contract with these folks, as a tenure track professor. How about you reframe academia in your mind as a challenge to pour academia’s resources right back at our People? Just direct those resources towards our People.” And that to me seemed like a great goal.

And I love teaching, it turns out. And I love research, it turns out. But the reality is I love my People more. And the work that I choose to do as a scholar is to find ways to meet our People’s needs, through using university resources, but also through understanding how academia works. And working in my sphere of influence to change my department, to change fellowship programs that I’m involved with. To create pathways towards this school, if people choose it. To give them the support that they need. To create a way that this isn’t such a harsh place.

I work hard to hold space for people in my community to get involved in research, or just to get involved in academic practices at all. And just to demystify it. And then also just to create a path for Inuit students to follow. Because I had to kind of make that path myself, and I know how hard it can be.

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

And I myself, I don’t desire to get a degree. I never did.

I remember having a conversation with our team in the health organization. We were talking about elevating the voices of the local people, and getting a seat at the table of decision-making. And one of the psychologists was saying, “Well, we just need to encourage them to go to school, and get educated, and then they’ll have a sit at the table, and be able to put their voice in.” And I said, “No.” And this was someone who was absolutely amazing, equity-minded, all of that.

But that was what they really believed, because that’s what we’ve been trained to believe. We’ve always been told in the village, “Go out, get your education, come back and help your People.” That’s the thing. And for me, I never desired it. And I’m not going to be thought less than, because of that. I am educated. I’m self-educated, and I’m community-educated.

I got my GED, but many of our People only went to high school. Many of them were sent to boarding schools, and didn’t go any further than that. But they are expert sled-makers, or they know about going out in the country, and what kind of weather with this cloud in the sky means, and why you shouldn’t go there to the yellow cloud in the sky because it’s open water.

So as I help to develop youth programs and raising up leadership, I always want to make sure that it’s the wisdom of our People that is considered education. We have our own educational system in the village. We always have. But it’s more of an apprenticeship model of education in degrees, that you graduate. You graduate to be able to cut the fish at a certain age. And I’ve been present when an 11 year-old is going, “I can’t believe it. This year is my year.”

There’s this level of wisdom that happens in a whole different system, in a whole different way, and that is equal to a Western education system. That needs to be acknowledged in every respect.

Image Credits: Cana Uluak Itchuaqiyaq and Corina Qaaġraq Kramer

FRANCISCO SOARES

In what ways would you like to see your work being implemented by others in the coming years? And what is making you hopeful about the future?

CORINA QAAĠRAQ KRAMER

Liam at NSF – a wonderful man, who has been a real champion for Indigenous work and research – he asked a similar question to me, at our first meeting together. He said, “What do you hope from all of this?” I think that we can be a voice to change the systems that affect our People globally. We can be a part of that change. And for some reason, we have this sort of magic, that really works in that respect, between the different communities, whether it’s the Indigenous communities or the academic communities.

We’re able to do that, and we see that there’s a bigger reach and a bigger need, globally. And there are many of us, Indigenous People, that are doing this very same thing. And so I just want to be a part of that community. And I want to help change things for our homes, which have many needs, needs that aren’t necessarily considered in research and academia.

CANA ULUAK ITCHUAQIYAQ

And for me, I want to help through the work that I do on the academic side, and how I translate this experience into publications, which are then used as tools by other people, to justify whatever change they are advocating for in their own work.

What would be success for me, is that I can retire from this gig of like, “Can we just do some equity, please?” Our dad was doing this in the early 90s. It’s been a long time that we’re asking the same thing.

And Corina and I, a lot of our recommendations are just, to us, really common sense. And so I would love it if people would engage in doing the work. And checking their motivations. And realizing that power-sharing is actually the key to this innovation in Arctic research. Sharing power, and hearing about “the yellow cloud in the sky means open water,” and recognizing that as a scientific observation and a demonstration of scientific expertise.

And when someone says, “Hey, we’re interested in XYZ.” And the community is like, “Yes, we already kind of know what’s happening with that. It’s probably something about this.” To listen to them. Because what they’re going to say next is, “What we’re really interested in is this. Because this is something that’s coming. It’s creeping up, and we haven’t figured out what’s coming towards us.” Because in Kotzebue, in the Northwest Arctic area, and along this coast in Alaska, these frontline communities are facing climate change right now. And so academic curiosities aren’t saving homes, aren’t saving lives, aren’t saving cultural connection and community connection to the land. It’s not doing that work.

And so my goal is for people just to listen. To do the work. To get out of their own way, really, towards innovation and working with communities. Get out of your own way, so I can retire and do construction. Which is really what I want to do, build little houses and furniture, play in my workshop and wear an apron, and not worry about “Dr. So-and-so” acting messy at home. So please, that would make me happy.

External Link