Connecting the Dots with Edson Krenak

A far-reaching discussion on Indigenous rights in the green transition, the impact of Indigenous-led initiatives, the evolution of the Indigenous movement in Brazil, and the author, scholar and advocacy coordinator’s work with Cultural Survival and SIRGE Coalition.

In recent years, we have seen a global resurgence of the Indigenous movement. For the world’s Indigenous Peoples, in all their diversity, new technologies have brought greater visibility, anchored in these Peoples’ ability to construct their own narratives about the past, the present and the future – a momentous shift, considering that over the centuries these narratives were written and controlled by the West.

This new visibility has created bridges of solidarity between Indigenous Peoples, united around the common challenges they face, but also around the solutions that their worldviews offer for a sustainable and fairer future for humanity – one has only to think of the studies that demonstrate the links between Indigenous land stewardship and biodiversity preservation.

But this strengthening of Indigenous causes is also happening among non-Indigenous people all over the world. A museological view, one that equated Indigenous Peoples with pre-colonial times and their subsequent destruction, is being replaced by a growing awareness of Indigenous societies, cultures and languages as alive, vibrant and indispensable to the survival of our planet.

More than ever, it is essential to strengthen this resurgence of the Indigenous movement in the face of energy transition and environmental protection international policies. In this crucial moment we must ensure that the foundations of our common future protect human rights. And especially the rights of Indigenous Peoples, in whose territories natural resources and biodiversity are protected, essential for maintaining balanced ecosystems.

In the work of Edson Krenak all these issues intersect, creating a unique path of Indigenous rights activism. Edson is Advocacy Coordinator at Cultural Survival, and he leads the organization’s work in Brazil. He is also deeply involved in the Keepers of the Earth Indigenous-led Fund, through which Cultural Survival supports Indigenous-led projects focused on environmental protection and territorial sovereignty.

Alongside his work capacitating and supporting Indigenous organizations, Edson has dedicated his life to the dissemination of Indigenous cultures (including as an award-winning author), to the promotion of decolonized history education, and to the creation of alliances that strengthen the Indigenous movement, both in Brazil and internationally. We must also highlight his role on SIRGE Coalition‘s executive committee, an alliance that is doing remarkable work to ensure that the rights of Indigenous Peoples are respected in policies regarding the extraction of essential transition minerals. Edson is currently finishing his PhD in Legal Anthropology at the University of Vienna in Austria.

Play the video version below (English subtitles available), or scroll down for the podcast version and the transcript in English.

CONNECTING THE DOTS – PODCAST

Are you a podcast fan? Make sure you subscribe to the podcast version of our Connecting the Dots series here.

ENGLISH VERSION (dubbed):

ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT

Credit: SIRGE Coalition

MARIANA MARQUES (AZIMUTH WORLD FOUNDATION)

Edson, thank you so much for being here with us today. I’d like to start by asking you to tell us a bit more about your background, about your community, how you became involved in activism for Indigenous Peoples’ causes, and how that activism has evolved from the local and community level, to the national level in Brazil and then, of course, to the international level.

EDSON KRENAK

Like many Indigenous people living in cities, I somehow try to collect the pieces of our history. Because in many places Indigenous Peoples’ history doesn’t exist as a linear narrative, as a narrative that is easy to find. This narrative, this story, you have to construct it. Just like a jigsaw puzzle, you take all these different parts and you try to put them together. This is a consequence of actions taken during colonial times by the State, which doesn’t always fulfil its duty as the protector of minorities and Indigenous Peoples’ rights.

So my family, it became a family of refugees. It’s a family made of people who had to leave their ancestral lands and seek out other places to live, as did so many of Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples.

Not all members of the Krenak People live within their traditional territory. Some of them, more than half, had to move and settle in other areas, because of mining projects, such as Vale’s, Brazil’s huge multinational iron company. And after dealing with several conflicts, with violence and other problems, many families decided to move and search for other places where they could protect themselves and their children.

When I was born, my close family had already left the context of the traditional territory. And my father, seeing all of his children, – we’re a big family of 8 children, I have 4 brothers and 4 sisters – he said, “Look, to be Indigenous in Brazil is extremely difficult. We better completely embrace our Brazilian identity, and forget about this whole Indigenous thing.”

External Link

For Brazil’s persecuted Krenak people, justice arrives half a century later

https://news.mongabay.com/2021/10/for-brazils-persecuted-krenak-people-justice-arrives-half-a-century-later/

But as I visited our ancestral lands and listened to our family stories, as I spent time talking to my aunt and my uncle, many threads of my story were left unanswered. And as a teenager, as a young man, I began to ask questions about our Indigenous ancestors. And we began rethreading our story. And even though my father was reticent, because of the violence, because of the attacks, because of the shame, because of the many challenges faced by Indigenous Peoples in Brazil, despite all this, I ended up gradually returning to our origins.

This is when I visited our Krenak village. It’s called Vanuiri Indigenous Territory, in the interior of the São Paulo state. Different Indigenous Peoples live in Vanuiri. It’s a fully recognized and demarcated land, but it’s very small, and seven Indigenous Peoples live there, the Krenak being one of them. These are Peoples who have been diaspora victims since the 1940s and 1950s, since 70 or 80 years ago. And of course contacting with this reality caught my attention.

I went to university as I was getting closer to this reality, and so I started to get in touch with Indigenous students, Indigenous leaders, Indigenous activists, looking for ways to strengthen my identity again, my own family’s identity, but also that of my own community, of my own People.

So that’s how I gradually got involved with the Indigenous movement. And my great mentor – let’s say, one the two great mentors in my story – is Daniel Munduruku, a Brazilian Indigenous author. He came to visit the university where I was studying, and he introduced us to the Indigenous literary movement. The activism through literature movement.

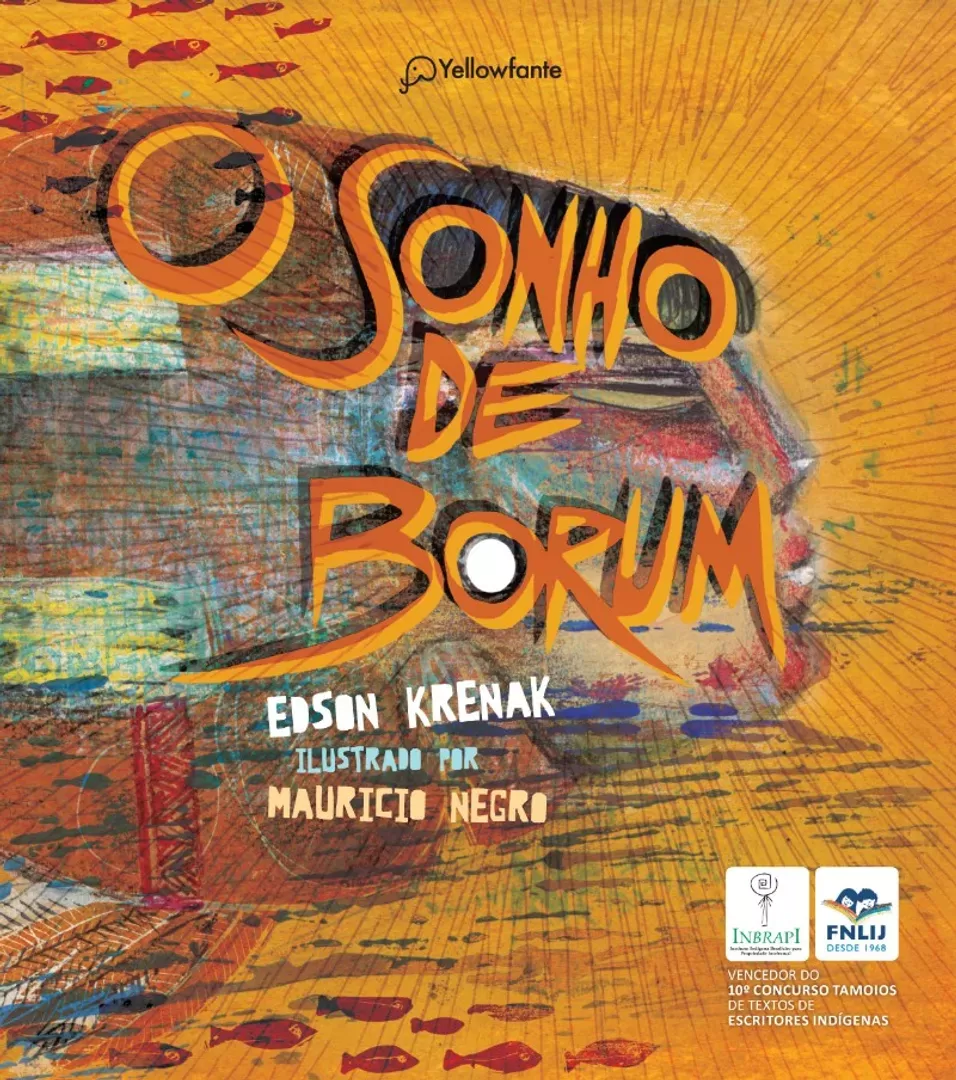

When I participated in a workshop he put together there, he read one of my texts. It was based on a story that my father and my uncle told frequently. And that’s the story I told in my first book, which ended up winning a prize. The book is called “Borum’s Dream”. When Daniel got his hands on this story, he read it and said, “Edson, this story is beautiful. You must share it with more people”. And that’s how we ended up publishing the book together.

I also got in touch with Ailton Krenak, who was deeply involved with the Indigenous literature movement at the time. And it was through networks, activists and movements – there are many Indigenous movements in Brazil – that we were able to expand our work, our reach, and our struggles as well.

So my advocacy work essentially begins with the Indigenous literature movement. A movement developed by Indigenous authors, united in their love for the stories that define us, for nature stories, for the stories that speak of our deep and ancestral relationships with the environment.

And it was during this period that we became even more aware – while meeting Indigenous authors, and visiting schools and universities in Brazil – of the prejudice, the many stereotypes, even the racism. Because most people didn’t know Indigenous people. In many places, people believed that Indigenous Peoples no longer existed, that they could only be found in books.

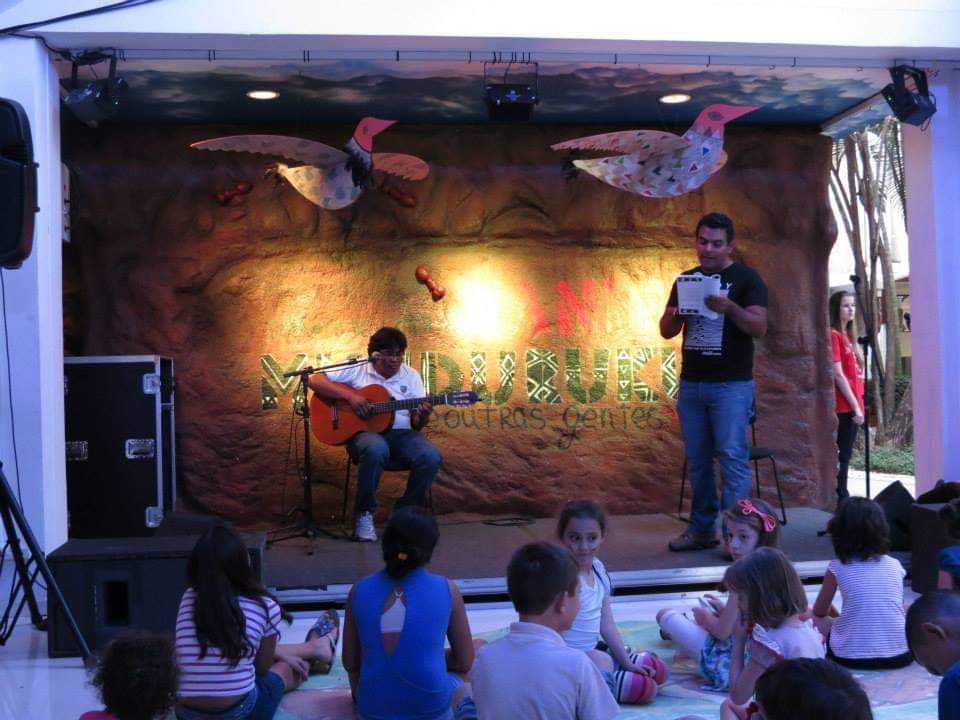

So we launched an Indigenous authors’ caravan. We named it Mekukradja, which means “transferring knowledge”, or “sharing knowledge”, in the Kayapó language. And we started visiting schools, universities, cultural institutes, communities, to tell Indigenous stories, to share our perspectives, in an attempt to clarify who Indigenous Peoples are. To say that we are still here, that we have survived. We survived the colonial period, we survived the military dictatorship. We survived throughout the 20th century, and here we are, living in the 21st century. And we want to build better relations with the society around us.

And then it became a national movement, because we visited places all over the country. The demand for our visits grew, as did the number of authors involved. When we went into villages and communities, we would discover other talented authors, artists and storytellers there. And we invited them to join our caravan.

And at some point we hosted an international gathering of Indigenous authors, in Brazil. We hosted an array of Indigenous authors, from Chile, Canada and other Latin American countries. And we could see several common aspects running through our different histories.

From Edson Krenak’s personal archive

And so I became more curious about Indigenous Peoples in other countries, and decided to search for PhD programs outside Brazil. I began looking for universities, and it was a very difficult process. Many universities, both inside and outside Brazil, still have a hard time understanding the dynamics of Indigenous knowledge – these new and different ways of looking at scientific knowledge – and Indigenous epistemologies. It’s obvious that we can produce knowledge. And then the universe’s mysterious ways, let’s put it that way, led me to Vienna, where I began studying at the University of Vienna.

And it became obvious, as I was developing my PhD project, that I needed to do it in conversation with the communities. Because Indigenous research, it isn’t an individual pursuit. It can’t be a researcher’s individual project. Indigenous research, we even call it a ceremony, through which we build collective knowledge to meet our collective demands. And talking with my community, and with other communities in Brazil, I asked them, “What can I research in my PhD program that would be important for you? What would be relevant to the community?”

Because we witness a lot of research here, very colonizing research. It’s a recurrent story within Indigenous communities. A researcher goes there, produces knowledge, and it only serves him, it only serves the university, and it doesn’t serve the community. And the community will never hear about this research again.

So in many ways they outlined my PhD, my academic research project. And they told me, “Look, the most important thing for us is our territory, our land. You must find ways of expressing what it means to us. Secondly, our rights. How we conceive of our rights, and how we would like this to be understood outside of Brazil.”

Then Lidiane Krenak, my cacica [chieftain], she said, “Edson, you need to bring our struggle to places we can’t reach ourselves. And in that struggle you must defend our cultural rights, your research has to contribute to that”.

From Edson Krenak’s personal archive

So when I came to Vienna, I connected with other international Indigenous movements. I came across Cultural Survival at an event here, at a conference. And that led to an invitation to work with them. At first, as a consultant. And then we looked more closely at the needs on the ground, in Brazil, and we worked from that assessment. In my second year working with Cultural Survival, there was a boom around the issue of transition minerals, the minerals that are essential for battery technology, for electric cars, etc…

And this happened for two reasons. First, proposals for new legislation were being discussed in the European Union, in settings like the OECD. Through this legislation, they began to discuss, “How are we going to access the minerals we need for this new digital revolution, for the so-called green energy revolution?” That was the first aspect, the legal aspect.

The second aspect involved listing how many mines they would need, where the mineral deposits lay, and where they were going to launch mining operations. And we realized that the locations of 55% of the mines for these minerals, they were going to directly impact Indigenous Peoples. 55%. “Well, we need to do something about this. We can’t let governments and companies make these decisions on their own, when they will have this impact on Indigenous communities.”

And we launched this coalition of Indigenous and non-Indigenous international organizations, so that we could stand up to this, so that we could ensure that Indigenous Peoples’ rights in this green energy transition can be protected, so that Indigenous Peoples are not left behind in this transition, so that they can contribute to it, and also receive the benefits of this transition.

So that’s how one thing led to another, seeking information, always focusing on what the community needs are. That’s how this work ended up reaching an international dimension.

External Link

MARIANA MARQUES

Can you share a little more with us about the growth of the Indigenous movement in Brazil?

EDSON KRENAK

I divide it in three main periods, the development of the Indigenous movement in Brazil over the last few decades.

There is the period before the 1988 Constitution, which was characterized by a struggle for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and for the recognition their existence. Until the 1988 Constitution, we weren’t even fully recognized as human beings. We were seen as subhuman, as inferior, as peoples who needed to be under tutelage.

This first moment of recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ existence, it reached its apex with the 1988 Constitution. There, not only was the existence of Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples recognized, but also their right to live as they wish. The Constitution recognized the sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples over their lands, resources, language, culture and lifeways. This Constitution was not a gift from the Brazilian government, it was hard-won through Indigenous Peoples’ struggle.

Then the second phase was a struggle for the demarcation of territories. This was already contemplated in the 1988 Constitution, and so we needed to have maps recognized in Brazilian documents, in legislation and in public policies. So this was a very important moment. And in fact, it is still going on. But just to be clear, during the first decade of this second phase, land demarcation was just related to the protection of Indigenous cultures.

Only with Rio ’92, for example through the voice of the late Paulinho Paiakan, who was a very important Indigenous leader, and one of my spiritual mentors and teachers at the beginning… Unfortunately, COVID-19 ended up taking his life. It was at that time, as Eco ’92 was held Brazil, that Indigenous Peoples also affirmed the profound relationship between the demarcation of Indigenous Lands and environmental protection. So that’s how a third phase begins, affirming Indigenous Peoples as the guardians of biodiversity.

So nowadays the Indigenous movement in Brazil carries that struggle for the recognition of our existence. It carries the struggle for land, for our traditional territories. And it currently also carries very strongly the message that when the government demarcates Indigenous Territories, it is protecting the environment.

External Link

WePresent | Powerful portraits of Brazil’s Indigenous resistance

https://wepresent.wetransfer.com/stories/o-futuro-e-indigena-alice-aedy-eric-terena

We began sharing our struggles among us. We had, and still have, at the local, regional, national and even international levels, Indigenous meetings and Indigenous assemblies. Many organizations were created. Regional organizations, like APOINME, which is the Association of Indigenous Peoples of the Northeast, the Association of Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon Basin, the Association of Indigenous Peoples of the Pantanal, of the Cerrado, of each biome.

So this movement surges with a lot of strength, from the bottom up. And it has taken on a national dimension. It’s not restricted to local and regional organizations fighting for their rights. When we realized that different governments – left, right, center, it doesn’t matter – weren’t solving Indigenous Peoples’ issues, we said, “Wait a minute, the governments are tackling the issues of hunger, of modernization, of industrialization, of education, issues that concern them. But our demands are not being met.”

It’s even worse than that, as our demands are actually under attack from new political conglomerates. You may be familiar with what is known in Brazil as the “Caucus of the 3 Bs”, which stands for bible, bullet and bovine. It includes Christian fundamentalists. I won’t say that all Christians are part of it, because we have Christian allies. “Bovine” means the agribusiness people, the cattle industry. And “Bullet” means people related to the military, and these people have a lot of political power in Brazil.

So they got together and proposed an interpretation of the ’88 Constitution – which is not only immoral, but has even been declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court – called the Temporal Framework [Marco Temporal]. According to it, the recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ existence can only happen if they were living in their own territories when the ’88 Constitution was ratified. This is an attempt to erase our history. A history of forced removal, of violence, of the destruction of our lands, of invasion.

External Link

Brazil’s Congress Weakens Protection of Indigenous Lands, Defying Lula - The New York Times

It’s a very dangerous interpretation, and it continues to be argued in court. If it goes through, the right to traditional land is transferred to the private sector. Traditional communities will lose their rights, in favor of the private sector. And the private sector is 100% responsible for deforestation, mining, burning and a series of other problems, with very serious environmental impacts in Brazil. And this also impacts communities here in Europe.

By tracing the chain of products that are produced in Brazil and sold here in Europe, you will see that agrotoxins that are banned in Europe are used in Brazil, to produce food that is sold in Europe. You will find food, mineral products and other raw materials that are produced on deforested land, on destroyed land, in destroyed and burnt down forests, that contaminate rivers, being sold in Europe.

And so we kept on building this movement, from the bottom up. Here, “up” represents those instances when we defend our rights in a national or international court, when we bring our struggles to the federal government and the city council. And Indigenous Peoples’ participation in these settings is huge now.

Many Indigenous Peoples are realizing that just going to court won’t do. We must be part of the court. Convincing politicians won’t do. We must become politicians, too. There’s no point in trying to lobby the Ministry. We need to have our own Ministry. So the movement has reached a new scale. And today, in Brazil, despite all the limitations, we are perhaps the only country in the world that has a Ministry of State for Indigenous Peoples, led by an Indigenous leader, Sônia Guajajara.

External Link

“Never again without us”: Indigenous Peoples’ Ministry in Brazil - Amazônia Real

MARIANA MARQUES

Do you think that technology has contributed to young people from different Indigenous communities joining the political struggle for the rights of Indigenous Peoples? And how does Indigenous art, including literature, contribute to the Indigenous movement in Brazil?

EDSON KRENAK

We often say that the heart of the Indigenous community, of Indigenous Peoples, is the territory and the language. Language, like all languages in the world, carries history within it. But language is also a form of technology, of communication technology. And many of our Peoples have various technologies for communicating with each other. And also technologies related to food, technologies related to living well, related to a lifestyle that doesn’t harm the environment.

And we have realized that in order to talk to modern man, to the man of today, to talk to today’s communities, to talk to the non-Indigenous community, it’s important to use other technologies as well. Many people think that when Indigenous Peoples use electronic technologies, for example, they are no longer Indigenous. But this is ignorant. Wearing certain clothes or speaking an Indigenous language doesn’t make someone Indigenous. So the opposite is true as well. We use technologies for the community’s common good, and also to strengthen our struggle, to help others understand us.

Because since time immemorial, we’ve had, for example, shamans or pajés, as we call them in Brazil. They would go on many diplomatic journeys and learned other languages. Many communities have always been able to speak 4 or 5 foreign languages. This allowed them to learn about other technologies, innovations and ideas. And it also avoided war, or helped create new forms of relationships in the forest.

So language is very important. Technologies play a fundamental role in amplifying our voice. Because now we no longer need the technology of paper, of books, through which the white man has always published about us. We can now publish books about ourselves. We can use technology to speak of ourselves. We can be here, together with you, using this technology to amplify our voice, to strengthen our work.

The challenge for young people today is to embrace these technologies, without abandoning traditional knowledge, without abandoning the communities.

External Link

Indigenous communicators unite traditional knowledge and new technologies to strengthen the fight | Socioenvironmental Institute

MARIANA MARQUES

It seems that after the blatant violence and impunity that marked Jair Bolsonaro’s rule, Lula’s election was seen as a source of hope in the fight to defend Indigenous Peoples’ rights in Brazil.

While the creation of the Ministry of Indigenous People and the Indigenous leadership of FUNAI were positive steps, we still continue to witness countless situations that negate this improvement narrative. How would you characterize the current moment that Indigenous communities in Brazil are going through?

EDSON KRENAK

It’s very hard to do so. Because it’s a complex and very important question. We have to find an answer almost every day.

When you read our legislation, and how Brazil is implementing, or incorporating, international mechanisms to protect Indigenous Peoples and other traditional communities, it is very beautiful. But then you realize that the law, that justice, they have a limit. And that limit is the political limit. And that’s why it’s no use having strong laws if the political will isn’t strong.

The great challenge for the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples in Brazil is to convince Brazil’s political will. It’s to make this political will – the large sector of the Brazilian community that voted for, approved of, supported and still supports Bolsonaro – aware of our demands, our concerns.

Bolsonaro’s four years didn’t come out of nowhere. Before Bolsonaro – two, three years before – Dilma Rousseff was impeached. And we had Michel Temer’s transitional government, which paved the way for Bolsonaro. In two or three years, Brazil went from being an environmental champion to having one of the worst environmental protection records in the world, under Temer and Bolsonaro. They dismantled all these structures that were protecting the environment and Indigenous Peoples.

External Link

Attacks on indigenous people doubled during the Bolsonaro years: almost 800 were killed

And currently, Lula’s government has started on a path which, according to him, according to the government, aims first and foremost to rebuild these structures so that they can be effective. Our criticism is that it’s happening too slowly. The number one task of the Brazilian President, according to the Constitution, is to demarcate Indigenous Territories. And we’re now more than two years into Lula’s administration, and he has only demarcated 6 Territories. And there are 14 others, with all the demarcation criteria already met, already complete. 14 Territories that meet every single criteria. These processes are sitting on his desk, just waiting for him to sign, and he’s not signing. Nobody knows why.

The Ministry still doesn’t have the political strength to force the President, to pressure him to do this. In addition, the Ministry faces another challenge, which is the budget. So that’s the problem for many politicians, and for Lula as well. The picture is prettier than the actual work being done. He looked really good in the picture, standing next to Indigenous Peoples. The whole world applauded it. But when it comes to actually creating a Ministry that has the power to make decisions, that has the power to fully operate, he still owes Indigenous Peoples.

External Link

Can Lula keep his promises to Indigenous peoples? - SUMAÚMA

For example, the Yanomami People, who live in an area that is bigger than Portugal. They are more or less 30,000 people, and they are protecting this enormous forest, full of life and biodiversity.

And during the Bolsonaro government, they suffered an invasion by 20,000 illegal land grabbers, miners and prospectors. Can you imagine? A population of 30,000 has to face 20,000 miners. And they’re coming in small, single-engine planes. They’ve been building illegal airstrips. They’re bringing drugs, they’re bringing prostitution, they’re bringing weapons, they’re bringing diseases that the people there don’t know about.

So, in many communities, when you go there, you’ll hear horrible stories. Really horrible stories. Of rape, of violence against women and Indigenous children. These illegal miners are in a forest the size of Portugal, and it’s very difficult to get them out. A large number have already left. But the government needs resources to maintain security operations there.

And the Guarani people, in Brazil’s center-west region, they are surrounded by industrial agriculture, which doesn’t want to give up an inch so that they can live their lives. And this industry is responsible for a series of environmental crimes, for crimes against Indigenous people, against Indigenous patrimony. So, in order to solve this problem, the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples needs the support of Brazil’s population. It needs to increase its political strength and its resources. And that is very difficult.

We’ve never had a Ministry. We’ve never had such a strong political presence as we do now, in 500 years of history. And we’ve only had this Ministry for two years now. So we need the many people who write about this, myself included, we all need to be a bit patient. The Ministry has existed for two years, after 500 years of devastation, 500 years of violence.

You used the word “hope”. It’s a very new word for Indigenous Peoples. Many of us don’t know this word, “hope”. Because we didn’t need it. Today, we need this word, because we live in contexts of violence. Our hope reaches for the past. We want to go back to how we were before, in harmony with the environment, developing our lives, our ways of being, of producing and living. Because that brought us peace. So what we want is peace and safety. As we had before.

So it’s a bit of an ambivalent position. On the one hand, we need to put pressure on the politicians. And on the other hand, we need to make good use of the benefits arising out of this visibility that we’ve never had before.

External Link

Brazil’s battle to reclaim Yanomami lands from illegal miners turns deadly

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/may/01/yanomami-territory-illegal-miners-death-toll

MARIANA MARQUES

As a member of Cultural Survival, you’ve been able to follow very closely the extraordinary work that Indigenous grassroots organizations do on a daily basis to protect their Territories and the environment.

What makes Indigenous-led grassroots projects so unique? And why is it so crucial to ensure that there are resources and funds, such as Keepers of the Earth, exclusively aimed at supporting these types of projects and grassroots organizations?

EDSON KRENAK

The work of Indigenous communities has several aspects that make these projects extremely important for them.

Firstly, it is an exercise in self-determination and self-governance. It’s a full exercise of all their rights. Of their right to live independently, in freedom, to live the way they choose to.

And secondly, these projects strengthen communities that were on the brink of extinction and extremely vulnerable. Communities that were under the threat of genocide, of ecocide. So these projects become, I won’t call it a resurrection, but a way of truly rejuvenating these communities. It’s an example to the world of how such vulnerable communities have the capacity for resistance and resilience, when they develop these projects.

And the third aspect I’d point out is that we are living through an unprecedented climate crisis. And we’re already at that stage where we’re saying, “It’s too late to prevent it”. If you read the newspapers, every week there are disasters connected with climate change and to global warming, taking place around the world. This signals a huge crisis. And the crisis is caused by the extractive, destructive way we develop our lives on the planet.

External Link

Floods in Rio Grande do Sul state affect 30,000 | Direitos Humanos

https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2024/05/13/floods-in-rio-grande-do-sul-state-affect-30-000-indigenous-individuals-entity-says-there-is-water-and-food-shortage

And Indigenous communities’ projects carry a message. The message is, “Look. It is possible to develop ways of life that protect the planet, that protect local economies, that protect the most vulnerable species, and they can bring life, peace, security and joy to the communities.” Because the future is communal. The future is ancestral, as we say. It’s the traditional forms of community life that are really going to save the planet. If it is in fact possible, at this point, to save the planet. Or rather, to save humanity.

Because, actually, as Ailton Krenak likes to say, it is humanity that is threatened by climate change. The planet will live on. It will undergo all these changes, and it will adapt. It will change, it will be transformed. But are we capable of adapting and transforming as quickly? We’re seeing that we’re not capable. With all these disasters happening, we’re just not. So Indigenous-led projects are very rich, because they come up with solutions that are both local and global.

External Link

Ailton Krenak: “Earth can leave us behind and go its own way” - UFRGS - Jornal da Universidade

MARIANA MARQUES

An important part of your work is rooted in garnering international visibility for Indigenous Peoples and building international alliances to strengthen the movement.

Would you say that a growing number of people are becoming aware of the struggles of Indigenous Peoples, and becoming allies, in Europe, for example? Is there increased recognition of the role that colonialism has played and continues to play in the lives of Indigenous communities?

EDSON KRENAK

One aspect of colonialism was the creation of laws, or public policies, or legislation, really, that could justify its actions. And what we see is that the European Union, for example, and blocs of countries at the geopolitical level, they create a lot of international mechanisms, international laws. And part of our job is to look at these laws, criticize these laws, and try to convince our allies, and the politicians here in Europe, to change these laws.

I’ll give you a very specific example, which is this new European Union directive on sustainability and business that deals with supply chain issues, and the raw materials supply chain. We fought very hard for them to put in place stronger mechanisms that can protect the environment and Indigenous Peoples. That can be done, for example, by forcing companies that do business outside of Europe to respect the rights of Indigenous communities to Free, Prior and Informed Consultation.

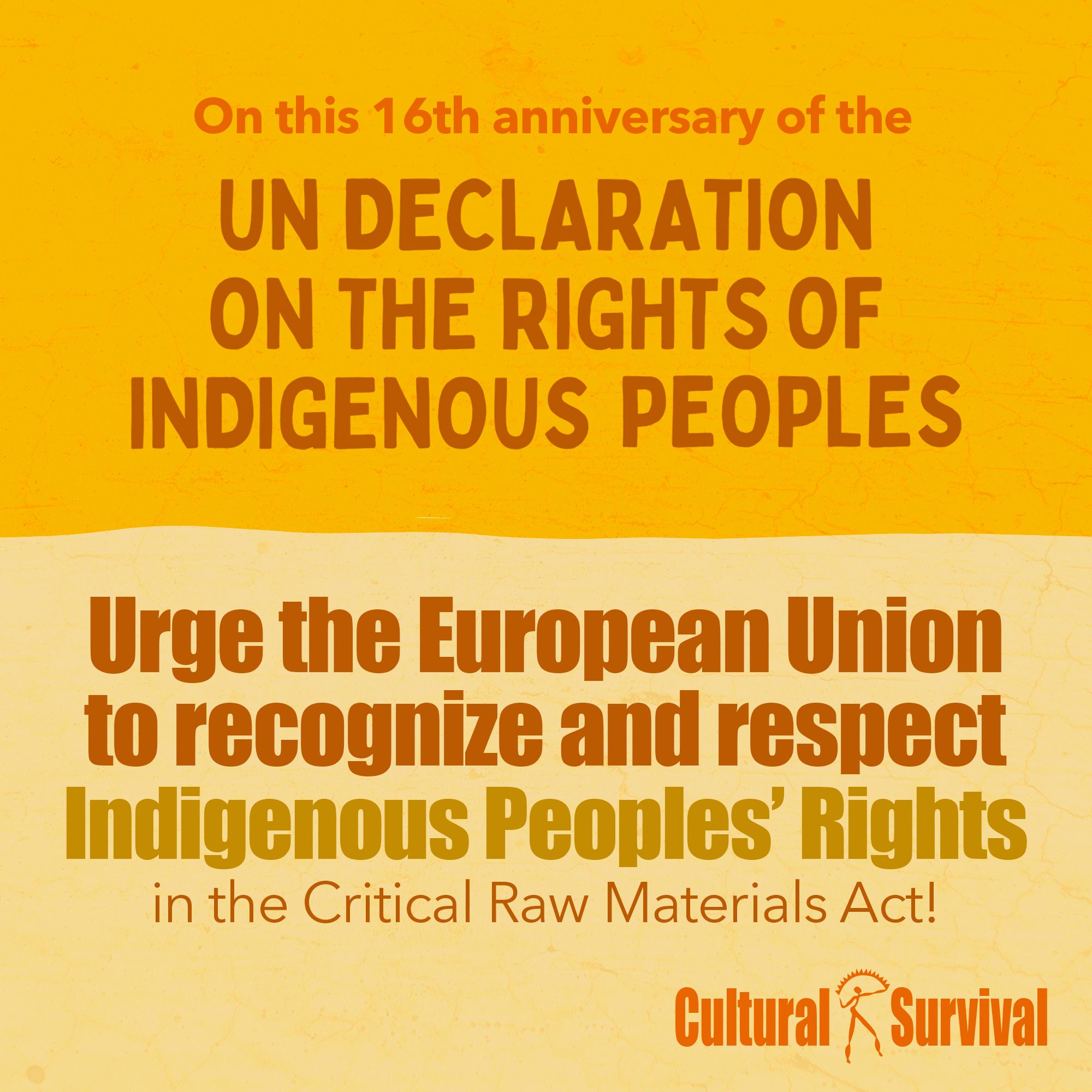

Because these consultations are a mechanism created by international law. Indigenous Peoples fought really hard to achieve this, to force companies and states to consult communities before establishing any project on their lands, in their territories. There was a big struggle, involving a lot of lobbying and discussions in the European Union, in the European Council, to try to prevent this consultation from being included in the final legislation. It ended up being mentioned in it. Is that a step forward? It is. But we wanted it to be in the actual text of that new directive, and also in the so-called Raw Materials Act, this new legislation, so that it would truly respect Indigenous Peoples and create stronger mechanisms to protect them.

External Link

The European Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive: Why Does It Matter for Indigenous Peoples?

So one of the things we’re doing is trying to convince people to become our allies, here in Europe. As a way to strengthen our advocacy work with these national and international legislative bodies here in Europe. But we also reach out to large companies. For example, car companies, and car factories that purchase minerals. Supermarket chains that purchase fruit. Pharmaceutical companies that get supplies from Brazil, and specifically from Indigenous communities and Indigenous territories. And we ask them to implement due diligence mechanisms.

We have had some success. It’s still not enough, but it’s important. Because it kind of allows us to get one foot in the door, and that is a source of hope for the future. That’s important. I’ve been collecting some positive, optimistic experiences when it comes to forging alliances here in Europe.

We have found that many organizations, and a large part of civil society, understand that Indigenous Peoples’ struggle is their struggle too. That it is a struggle for all of humanity, sharing the same boat, sailing in the same sea. And anything that happens to that boat, and on that sea, it will impact the whole world.

External Link

Urge the European Union to include Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) in its Critical Raw Materials Act

https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/urge-european-union-include-free-prior-and-informed-consent-fpic-its-critical-raw-materials

MARIANA MARQUES

And how do you get the message across about the common challenges that Indigenous communities face, while at the same time celebrating the enormous heterogeneity and plurality that exists among the different Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, and of the world? How do you balance these aspects?

EDSON KRENAK

It’s very difficult. There are times when I ask myself that question too. But it’s just like what happens in a big family. There are all these differences, but we always think, “What unites us is greater and more important than what separates us”. These separations are not all negative. There are many differences that are very positive. But what unites us is this love for Mother Earth. What unites us is this love and respect for what is human, respect for the different species, respect for biodiversity. This unites us all, it unites all Indigenous Peoples.

There are some sectors of society around the world for whom, unfortunately, the environment and biodiversity are not important. Big extractive companies, for example. But Indigenous Peoples have learned – even though we speak different languages – to use a common language when it comes to defending our rights.

Even the “Indigenous Peoples” terminology, many communities still dislike it. But they understand that the term “Indigenous Peoples” is connected to political struggle, to a context of interaction, of power relations with the state, with companies, with large corporations. So, in this context, we understand it.

External Link

Indigenous Women Uniting to Fight for Their Rights and the Earth - Rainforest Foundation US

MARIANA MARQUES

We know that a very significant part of essential transition minerals are located within Indigenous territories. This is an issue that SIRGE Coalition, of which you are a member of the executive committee, has been tirelessly dedicated to.

We also know that environmental protection policies, such as the much discussed “30×30” agenda, can lead to the forced eviction of Indigenous communities from their territories, in the name of an idea of conservation that excludes the presence of human beings in these protected areas.

How crucial is it to bring the reality of Indigenous Peoples into international debates on climate and energy transition, to ensure that this process is fair, based on the defense of human rights, and immune to the worst greenwashing instances?

EDSON KRENAK

SIRGE Coalition has a very strong strategy, in the sense that it tackles different areas. We have members who work directly with mining corporations. Others work directly with banks and investors. Others, like Cultural Survival, work directly with Indigenous communities. We have organizations that focus their work on the climate debate.

So the most important thing for us is to bring the demands and needs of Indigenous Peoples, their story, to these places. When we are able to show what is happening in Indigenous territories, that becomes our most powerful weapon.

I’ll give you an example. A large company came to us, in March, and showed us how the company’s policies on the environment and sustainability perfectly and fully followed all the guidelines. “Oh, OK, good. Compared to other companies, compared to the government, or even compared to the current legislation, you’re doing fine. Let’s talk to the communities living next to your projects”. And when we talk to the communities, it’s a totally different story.

The communities haven’t been consulted, as is happening right now in Brazil in relation to lithium, to the implementation of lithium projects. In the mining environmental impact reports, which the mining company sold – “sold” in the sense of “shared” – to the investors, there were no major environmental impacts. But in the territory, the community showed them to me. We walked around, and they said, “Look, five years ago, we had a river here, a stream here. Now it’s gone. It’s dried up”. They said, “Edson, the children used to walk here, they used to play in this area, in this street, peacefully. Nowadays they can’t do that anymore, because bats come to attack them every day. Bats are upset, stressed, because of the mining company’s presence.”

External Link

The Violent Cartography of Lithium in Brazil: Indigenous and Traditional Communities Struggle with the Giant of Transition Minerals in Brazil

Greenwashing won’t be pointed out by an auditing company. It won’t be identified through certification protocols, which are currently multiplying due to these transition minerals. Almost every week we hear about a new certification, a new standardization. Only local communities and Indigenous communities can do that. Indigenous communities possess data, lots of it.

And not just data. They also have the solutions. Because in those places where they have succeeded, even if in simple and small ways, they have been able to protect the things that protect life. So that’s the way Indigenous communities have been fighting back.

And I don’t need to tell you that it’s almost unfair, this fight. Because these communities, not only are they the most impacted by climate change, they are the ones reaping the least benefits from these transition and development policies. They receive almost no funding. There are almost no financial mechanisms or climate change mitigation mechanisms available to them. What Indigenous communities are still able to do is almost miraculous.

Because there is no insurance against environmental disaster in their communities, but there is a million-dollar insurance for a mining company. There is no powerful investor behind the community’s environmental projects, but there are national and international banks investing in mining companies. So this is our struggle. And that’s why I appreciate the work that Azimuth is doing, amplifying this issue, asking these very important questions, and sharing about what is happening, and how these issues are developing.

External Link

Climate funds for Indigenous Peoples 'evaporate' before reaching them, report reveals | Euronews

MARIANA MARQUES

Thank you for your words, Edson.

I was thinking of our listeners in Europe, for example, who may be accessing more testimonies from Indigenous voices, and becoming more aware of the struggle to protect Indigenous Peoples’ rights.

Still, these listeners can still ask themselves, “If I’m so far away, what can I do?” In your opinion, what are the best ways of becoming an ally of Indigenous Peoples, currently?

EDSON KRENAK

The best answer would be, “Come and spend some time in our communities, and learn from us, and join our fight there”. But I know that’s impossible, because the communities are small, they’re vulnerable, they have many challenges.

So the best way to start would be to learn about what Indigenous communities are doing. Learn about Indigenous organizations. Learn about European operations and activities that impact Indigenous communities. Support political and social projects that support these political communities.

And, of course, invite Indigenous people to come speak here. There are, not only in Brazil, but all over the world, Indigenous people, Indigenous leaders, Indigenous women, wonderful Indigenous youths, who are ready to share their stories, to teach, to work together and collaborate. So we need more collaboration.

External Link

Cultural Survival

https://www.culturalsurvival.org/

Connecting the Dots with Edson Krenak

A far-reaching discussion on Indigenous rights in the green transition, the impact of Indigenous-led initiatives, the evolution of the Indigenous movement in Brazil, and the author, scholar and advocacy coordinator’s work with Cultural Survival and SIRGE Coalition.

In recent years, we have seen a global resurgence of the Indigenous movement. For the world’s Indigenous Peoples, in all their diversity, new technologies have brought greater visibility, anchored in these Peoples’ ability to construct their own narratives about the past, the present and the future – a momentous shift, considering that over the centuries these narratives were written and controlled by the West.

This new visibility has created bridges of solidarity between Indigenous Peoples, united around the common challenges they face, but also around the solutions that their worldviews offer for a sustainable and fairer future for humanity – one has only to think of the studies that demonstrate the links between Indigenous land stewardship and biodiversity preservation.

But this strengthening of Indigenous causes is also happening among non-Indigenous people all over the world. A museological view, one that equated Indigenous Peoples with pre-colonial times and their subsequent destruction, is being replaced by a growing awareness of Indigenous societies, cultures and languages as alive, vibrant and indispensable to the survival of our planet.

More than ever, it is essential to strengthen this resurgence of the Indigenous movement in the face of energy transition and environmental protection international policies. In this crucial moment we must ensure that the foundations of our common future protect human rights. And especially the rights of Indigenous Peoples, in whose territories natural resources and biodiversity are protected, essential for maintaining balanced ecosystems.

In the work of Edson Krenak all these issues intersect, creating a unique path of Indigenous rights activism. Edson is Advocacy Coordinator at Cultural Survival, and he leads the organization’s work in Brazil. He is also deeply involved in the Keepers of the Earth Indigenous-led Fund, through which Cultural Survival supports Indigenous-led projects focused on environmental protection and territorial sovereignty.

Alongside his work capacitating and supporting Indigenous organizations, Edson has dedicated his life to the dissemination of Indigenous cultures (including as an award-winning author), to the promotion of decolonized history education, and to the creation of alliances that strengthen the Indigenous movement, both in Brazil and internationally. We must also highlight his role on SIRGE Coalition‘s executive committee, an alliance that is doing remarkable work to ensure that the rights of Indigenous Peoples are respected in policies regarding the extraction of essential transition minerals. Edson is currently finishing his PhD in Legal Anthropology at the University of Vienna in Austria.

Play the video version below (English subtitles available), or scroll down for the podcast version and the transcript in English.

CONNECTING THE DOTS – PODCAST

Are you a podcast fan? Make sure you subscribe to the podcast version of our Connecting the Dots series here.

ENGLISH VERSION (dubbed):

ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT

Credit: SIRGE Coalition

MARIANA MARQUES (AZIMUTH WORLD FOUNDATION)

Edson, thank you so much for being here with us today. I’d like to start by asking you to tell us a bit more about your background, about your community, how you became involved in activism for Indigenous Peoples’ causes, and how that activism has evolved from the local and community level, to the national level in Brazil and then, of course, to the international level.

EDSON KRENAK

Like many Indigenous people living in cities, I somehow try to collect the pieces of our history. Because in many places Indigenous Peoples’ history doesn’t exist as a linear narrative, as a narrative that is easy to find. This narrative, this story, you have to construct it. Just like a jigsaw puzzle, you take all these different parts and you try to put them together. This is a consequence of actions taken during colonial times by the State, which doesn’t always fulfil its duty as the protector of minorities and Indigenous Peoples’ rights.

So my family, it became a family of refugees. It’s a family made of people who had to leave their ancestral lands and seek out other places to live, as did so many of Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples.

Not all members of the Krenak People live within their traditional territory. Some of them, more than half, had to move and settle in other areas, because of mining projects, such as Vale’s, Brazil’s huge multinational iron company. And after dealing with several conflicts, with violence and other problems, many families decided to move and search for other places where they could protect themselves and their children.

When I was born, my close family had already left the context of the traditional territory. And my father, seeing all of his children, – we’re a big family of 8 children, I have 4 brothers and 4 sisters – he said, “Look, to be Indigenous in Brazil is extremely difficult. We better completely embrace our Brazilian identity, and forget about this whole Indigenous thing.”

External Link

For Brazil’s persecuted Krenak people, justice arrives half a century later

https://news.mongabay.com/2021/10/for-brazils-persecuted-krenak-people-justice-arrives-half-a-century-later/

But as I visited our ancestral lands and listened to our family stories, as I spent time talking to my aunt and my uncle, many threads of my story were left unanswered. And as a teenager, as a young man, I began to ask questions about our Indigenous ancestors. And we began rethreading our story. And even though my father was reticent, because of the violence, because of the attacks, because of the shame, because of the many challenges faced by Indigenous Peoples in Brazil, despite all this, I ended up gradually returning to our origins.

This is when I visited our Krenak village. It’s called Vanuiri Indigenous Territory, in the interior of the São Paulo state. Different Indigenous Peoples live in Vanuiri. It’s a fully recognized and demarcated land, but it’s very small, and seven Indigenous Peoples live there, the Krenak being one of them. These are Peoples who have been diaspora victims since the 1940s and 1950s, since 70 or 80 years ago. And of course contacting with this reality caught my attention.

I went to university as I was getting closer to this reality, and so I started to get in touch with Indigenous students, Indigenous leaders, Indigenous activists, looking for ways to strengthen my identity again, my own family’s identity, but also that of my own community, of my own People.

So that’s how I gradually got involved with the Indigenous movement. And my great mentor – let’s say, one the two great mentors in my story – is Daniel Munduruku, a Brazilian Indigenous author. He came to visit the university where I was studying, and he introduced us to the Indigenous literary movement. The activism through literature movement.

When I participated in a workshop he put together there, he read one of my texts. It was based on a story that my father and my uncle told frequently. And that’s the story I told in my first book, which ended up winning a prize. The book is called “Borum’s Dream”. When Daniel got his hands on this story, he read it and said, “Edson, this story is beautiful. You must share it with more people”. And that’s how we ended up publishing the book together.

I also got in touch with Ailton Krenak, who was deeply involved with the Indigenous literature movement at the time. And it was through networks, activists and movements – there are many Indigenous movements in Brazil – that we were able to expand our work, our reach, and our struggles as well.

So my advocacy work essentially begins with the Indigenous literature movement. A movement developed by Indigenous authors, united in their love for the stories that define us, for nature stories, for the stories that speak of our deep and ancestral relationships with the environment.

And it was during this period that we became even more aware – while meeting Indigenous authors, and visiting schools and universities in Brazil – of the prejudice, the many stereotypes, even the racism. Because most people didn’t know Indigenous people. In many places, people believed that Indigenous Peoples no longer existed, that they could only be found in books.

So we launched an Indigenous authors’ caravan. We named it Mekukradja, which means “transferring knowledge”, or “sharing knowledge”, in the Kayapó language. And we started visiting schools, universities, cultural institutes, communities, to tell Indigenous stories, to share our perspectives, in an attempt to clarify who Indigenous Peoples are. To say that we are still here, that we have survived. We survived the colonial period, we survived the military dictatorship. We survived throughout the 20th century, and here we are, living in the 21st century. And we want to build better relations with the society around us.

And then it became a national movement, because we visited places all over the country. The demand for our visits grew, as did the number of authors involved. When we went into villages and communities, we would discover other talented authors, artists and storytellers there. And we invited them to join our caravan.

And at some point we hosted an international gathering of Indigenous authors, in Brazil. We hosted an array of Indigenous authors, from Chile, Canada and other Latin American countries. And we could see several common aspects running through our different histories.

From Edson Krenak’s personal archive

And so I became more curious about Indigenous Peoples in other countries, and decided to search for PhD programs outside Brazil. I began looking for universities, and it was a very difficult process. Many universities, both inside and outside Brazil, still have a hard time understanding the dynamics of Indigenous knowledge – these new and different ways of looking at scientific knowledge – and Indigenous epistemologies. It’s obvious that we can produce knowledge. And then the universe’s mysterious ways, let’s put it that way, led me to Vienna, where I began studying at the University of Vienna.

And it became obvious, as I was developing my PhD project, that I needed to do it in conversation with the communities. Because Indigenous research, it isn’t an individual pursuit. It can’t be a researcher’s individual project. Indigenous research, we even call it a ceremony, through which we build collective knowledge to meet our collective demands. And talking with my community, and with other communities in Brazil, I asked them, “What can I research in my PhD program that would be important for you? What would be relevant to the community?”

Because we witness a lot of research here, very colonizing research. It’s a recurrent story within Indigenous communities. A researcher goes there, produces knowledge, and it only serves him, it only serves the university, and it doesn’t serve the community. And the community will never hear about this research again.

So in many ways they outlined my PhD, my academic research project. And they told me, “Look, the most important thing for us is our territory, our land. You must find ways of expressing what it means to us. Secondly, our rights. How we conceive of our rights, and how we would like this to be understood outside of Brazil.”

Then Lidiane Krenak, my cacica [chieftain], she said, “Edson, you need to bring our struggle to places we can’t reach ourselves. And in that struggle you must defend our cultural rights, your research has to contribute to that”.

From Edson Krenak’s personal archive

So when I came to Vienna, I connected with other international Indigenous movements. I came across Cultural Survival at an event here, at a conference. And that led to an invitation to work with them. At first, as a consultant. And then we looked more closely at the needs on the ground, in Brazil, and we worked from that assessment. In my second year working with Cultural Survival, there was a boom around the issue of transition minerals, the minerals that are essential for battery technology, for electric cars, etc…

And this happened for two reasons. First, proposals for new legislation were being discussed in the European Union, in settings like the OECD. Through this legislation, they began to discuss, “How are we going to access the minerals we need for this new digital revolution, for the so-called green energy revolution?” That was the first aspect, the legal aspect.

The second aspect involved listing how many mines they would need, where the mineral deposits lay, and where they were going to launch mining operations. And we realized that the locations of 55% of the mines for these minerals, they were going to directly impact Indigenous Peoples. 55%. “Well, we need to do something about this. We can’t let governments and companies make these decisions on their own, when they will have this impact on Indigenous communities.”

And we launched this coalition of Indigenous and non-Indigenous international organizations, so that we could stand up to this, so that we could ensure that Indigenous Peoples’ rights in this green energy transition can be protected, so that Indigenous Peoples are not left behind in this transition, so that they can contribute to it, and also receive the benefits of this transition.

So that’s how one thing led to another, seeking information, always focusing on what the community needs are. That’s how this work ended up reaching an international dimension.

External Link

MARIANA MARQUES

Can you share a little more with us about the growth of the Indigenous movement in Brazil?

EDSON KRENAK

I divide it in three main periods, the development of the Indigenous movement in Brazil over the last few decades.

There is the period before the 1988 Constitution, which was characterized by a struggle for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and for the recognition their existence. Until the 1988 Constitution, we weren’t even fully recognized as human beings. We were seen as subhuman, as inferior, as peoples who needed to be under tutelage.

This first moment of recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ existence, it reached its apex with the 1988 Constitution. There, not only was the existence of Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples recognized, but also their right to live as they wish. The Constitution recognized the sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples over their lands, resources, language, culture and lifeways. This Constitution was not a gift from the Brazilian government, it was hard-won through Indigenous Peoples’ struggle.

Then the second phase was a struggle for the demarcation of territories. This was already contemplated in the 1988 Constitution, and so we needed to have maps recognized in Brazilian documents, in legislation and in public policies. So this was a very important moment. And in fact, it is still going on. But just to be clear, during the first decade of this second phase, land demarcation was just related to the protection of Indigenous cultures.

Only with Rio ’92, for example through the voice of the late Paulinho Paiakan, who was a very important Indigenous leader, and one of my spiritual mentors and teachers at the beginning… Unfortunately, COVID-19 ended up taking his life. It was at that time, as Eco ’92 was held Brazil, that Indigenous Peoples also affirmed the profound relationship between the demarcation of Indigenous Lands and environmental protection. So that’s how a third phase begins, affirming Indigenous Peoples as the guardians of biodiversity.

So nowadays the Indigenous movement in Brazil carries that struggle for the recognition of our existence. It carries the struggle for land, for our traditional territories. And it currently also carries very strongly the message that when the government demarcates Indigenous Territories, it is protecting the environment.

External Link

WePresent | Powerful portraits of Brazil’s Indigenous resistance

https://wepresent.wetransfer.com/stories/o-futuro-e-indigena-alice-aedy-eric-terena

We began sharing our struggles among us. We had, and still have, at the local, regional, national and even international levels, Indigenous meetings and Indigenous assemblies. Many organizations were created. Regional organizations, like APOINME, which is the Association of Indigenous Peoples of the Northeast, the Association of Indigenous Peoples of the Amazon Basin, the Association of Indigenous Peoples of the Pantanal, of the Cerrado, of each biome.

So this movement surges with a lot of strength, from the bottom up. And it has taken on a national dimension. It’s not restricted to local and regional organizations fighting for their rights. When we realized that different governments – left, right, center, it doesn’t matter – weren’t solving Indigenous Peoples’ issues, we said, “Wait a minute, the governments are tackling the issues of hunger, of modernization, of industrialization, of education, issues that concern them. But our demands are not being met.”

It’s even worse than that, as our demands are actually under attack from new political conglomerates. You may be familiar with what is known in Brazil as the “Caucus of the 3 Bs”, which stands for bible, bullet and bovine. It includes Christian fundamentalists. I won’t say that all Christians are part of it, because we have Christian allies. “Bovine” means the agribusiness people, the cattle industry. And “Bullet” means people related to the military, and these people have a lot of political power in Brazil.

So they got together and proposed an interpretation of the ’88 Constitution – which is not only immoral, but has even been declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court – called the Temporal Framework [Marco Temporal]. According to it, the recognition of Indigenous Peoples’ existence can only happen if they were living in their own territories when the ’88 Constitution was ratified. This is an attempt to erase our history. A history of forced removal, of violence, of the destruction of our lands, of invasion.

External Link

Brazil’s Congress Weakens Protection of Indigenous Lands, Defying Lula - The New York Times

It’s a very dangerous interpretation, and it continues to be argued in court. If it goes through, the right to traditional land is transferred to the private sector. Traditional communities will lose their rights, in favor of the private sector. And the private sector is 100% responsible for deforestation, mining, burning and a series of other problems, with very serious environmental impacts in Brazil. And this also impacts communities here in Europe.

By tracing the chain of products that are produced in Brazil and sold here in Europe, you will see that agrotoxins that are banned in Europe are used in Brazil, to produce food that is sold in Europe. You will find food, mineral products and other raw materials that are produced on deforested land, on destroyed land, in destroyed and burnt down forests, that contaminate rivers, being sold in Europe.

And so we kept on building this movement, from the bottom up. Here, “up” represents those instances when we defend our rights in a national or international court, when we bring our struggles to the federal government and the city council. And Indigenous Peoples’ participation in these settings is huge now.

Many Indigenous Peoples are realizing that just going to court won’t do. We must be part of the court. Convincing politicians won’t do. We must become politicians, too. There’s no point in trying to lobby the Ministry. We need to have our own Ministry. So the movement has reached a new scale. And today, in Brazil, despite all the limitations, we are perhaps the only country in the world that has a Ministry of State for Indigenous Peoples, led by an Indigenous leader, Sônia Guajajara.

External Link

“Never again without us”: Indigenous Peoples’ Ministry in Brazil - Amazônia Real

MARIANA MARQUES

Do you think that technology has contributed to young people from different Indigenous communities joining the political struggle for the rights of Indigenous Peoples? And how does Indigenous art, including literature, contribute to the Indigenous movement in Brazil?

EDSON KRENAK

We often say that the heart of the Indigenous community, of Indigenous Peoples, is the territory and the language. Language, like all languages in the world, carries history within it. But language is also a form of technology, of communication technology. And many of our Peoples have various technologies for communicating with each other. And also technologies related to food, technologies related to living well, related to a lifestyle that doesn’t harm the environment.

And we have realized that in order to talk to modern man, to the man of today, to talk to today’s communities, to talk to the non-Indigenous community, it’s important to use other technologies as well. Many people think that when Indigenous Peoples use electronic technologies, for example, they are no longer Indigenous. But this is ignorant. Wearing certain clothes or speaking an Indigenous language doesn’t make someone Indigenous. So the opposite is true as well. We use technologies for the community’s common good, and also to strengthen our struggle, to help others understand us.

Because since time immemorial, we’ve had, for example, shamans or pajés, as we call them in Brazil. They would go on many diplomatic journeys and learned other languages. Many communities have always been able to speak 4 or 5 foreign languages. This allowed them to learn about other technologies, innovations and ideas. And it also avoided war, or helped create new forms of relationships in the forest.

So language is very important. Technologies play a fundamental role in amplifying our voice. Because now we no longer need the technology of paper, of books, through which the white man has always published about us. We can now publish books about ourselves. We can use technology to speak of ourselves. We can be here, together with you, using this technology to amplify our voice, to strengthen our work.

The challenge for young people today is to embrace these technologies, without abandoning traditional knowledge, without abandoning the communities.

External Link

Indigenous communicators unite traditional knowledge and new technologies to strengthen the fight | Socioenvironmental Institute

MARIANA MARQUES

It seems that after the blatant violence and impunity that marked Jair Bolsonaro’s rule, Lula’s election was seen as a source of hope in the fight to defend Indigenous Peoples’ rights in Brazil.

While the creation of the Ministry of Indigenous People and the Indigenous leadership of FUNAI were positive steps, we still continue to witness countless situations that negate this improvement narrative. How would you characterize the current moment that Indigenous communities in Brazil are going through?

EDSON KRENAK

It’s very hard to do so. Because it’s a complex and very important question. We have to find an answer almost every day.

When you read our legislation, and how Brazil is implementing, or incorporating, international mechanisms to protect Indigenous Peoples and other traditional communities, it is very beautiful. But then you realize that the law, that justice, they have a limit. And that limit is the political limit. And that’s why it’s no use having strong laws if the political will isn’t strong.

The great challenge for the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples in Brazil is to convince Brazil’s political will. It’s to make this political will – the large sector of the Brazilian community that voted for, approved of, supported and still supports Bolsonaro – aware of our demands, our concerns.

Bolsonaro’s four years didn’t come out of nowhere. Before Bolsonaro – two, three years before – Dilma Rousseff was impeached. And we had Michel Temer’s transitional government, which paved the way for Bolsonaro. In two or three years, Brazil went from being an environmental champion to having one of the worst environmental protection records in the world, under Temer and Bolsonaro. They dismantled all these structures that were protecting the environment and Indigenous Peoples.

External Link

Attacks on indigenous people doubled during the Bolsonaro years: almost 800 were killed

And currently, Lula’s government has started on a path which, according to him, according to the government, aims first and foremost to rebuild these structures so that they can be effective. Our criticism is that it’s happening too slowly. The number one task of the Brazilian President, according to the Constitution, is to demarcate Indigenous Territories. And we’re now more than two years into Lula’s administration, and he has only demarcated 6 Territories. And there are 14 others, with all the demarcation criteria already met, already complete. 14 Territories that meet every single criteria. These processes are sitting on his desk, just waiting for him to sign, and he’s not signing. Nobody knows why.

The Ministry still doesn’t have the political strength to force the President, to pressure him to do this. In addition, the Ministry faces another challenge, which is the budget. So that’s the problem for many politicians, and for Lula as well. The picture is prettier than the actual work being done. He looked really good in the picture, standing next to Indigenous Peoples. The whole world applauded it. But when it comes to actually creating a Ministry that has the power to make decisions, that has the power to fully operate, he still owes Indigenous Peoples.

External Link

Can Lula keep his promises to Indigenous peoples? - SUMAÚMA

For example, the Yanomami People, who live in an area that is bigger than Portugal. They are more or less 30,000 people, and they are protecting this enormous forest, full of life and biodiversity.

And during the Bolsonaro government, they suffered an invasion by 20,000 illegal land grabbers, miners and prospectors. Can you imagine? A population of 30,000 has to face 20,000 miners. And they’re coming in small, single-engine planes. They’ve been building illegal airstrips. They’re bringing drugs, they’re bringing prostitution, they’re bringing weapons, they’re bringing diseases that the people there don’t know about.

So, in many communities, when you go there, you’ll hear horrible stories. Really horrible stories. Of rape, of violence against women and Indigenous children. These illegal miners are in a forest the size of Portugal, and it’s very difficult to get them out. A large number have already left. But the government needs resources to maintain security operations there.

And the Guarani people, in Brazil’s center-west region, they are surrounded by industrial agriculture, which doesn’t want to give up an inch so that they can live their lives. And this industry is responsible for a series of environmental crimes, for crimes against Indigenous people, against Indigenous patrimony. So, in order to solve this problem, the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples needs the support of Brazil’s population. It needs to increase its political strength and its resources. And that is very difficult.

We’ve never had a Ministry. We’ve never had such a strong political presence as we do now, in 500 years of history. And we’ve only had this Ministry for two years now. So we need the many people who write about this, myself included, we all need to be a bit patient. The Ministry has existed for two years, after 500 years of devastation, 500 years of violence.

You used the word “hope”. It’s a very new word for Indigenous Peoples. Many of us don’t know this word, “hope”. Because we didn’t need it. Today, we need this word, because we live in contexts of violence. Our hope reaches for the past. We want to go back to how we were before, in harmony with the environment, developing our lives, our ways of being, of producing and living. Because that brought us peace. So what we want is peace and safety. As we had before.

So it’s a bit of an ambivalent position. On the one hand, we need to put pressure on the politicians. And on the other hand, we need to make good use of the benefits arising out of this visibility that we’ve never had before.

External Link

Brazil’s battle to reclaim Yanomami lands from illegal miners turns deadly

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/may/01/yanomami-territory-illegal-miners-death-toll

MARIANA MARQUES

As a member of Cultural Survival, you’ve been able to follow very closely the extraordinary work that Indigenous grassroots organizations do on a daily basis to protect their Territories and the environment.

What makes Indigenous-led grassroots projects so unique? And why is it so crucial to ensure that there are resources and funds, such as Keepers of the Earth, exclusively aimed at supporting these types of projects and grassroots organizations?

EDSON KRENAK

The work of Indigenous communities has several aspects that make these projects extremely important for them.

Firstly, it is an exercise in self-determination and self-governance. It’s a full exercise of all their rights. Of their right to live independently, in freedom, to live the way they choose to.

And secondly, these projects strengthen communities that were on the brink of extinction and extremely vulnerable. Communities that were under the threat of genocide, of ecocide. So these projects become, I won’t call it a resurrection, but a way of truly rejuvenating these communities. It’s an example to the world of how such vulnerable communities have the capacity for resistance and resilience, when they develop these projects.

And the third aspect I’d point out is that we are living through an unprecedented climate crisis. And we’re already at that stage where we’re saying, “It’s too late to prevent it”. If you read the newspapers, every week there are disasters connected with climate change and to global warming, taking place around the world. This signals a huge crisis. And the crisis is caused by the extractive, destructive way we develop our lives on the planet.

External Link

Floods in Rio Grande do Sul state affect 30,000 | Direitos Humanos

https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2024/05/13/floods-in-rio-grande-do-sul-state-affect-30-000-indigenous-individuals-entity-says-there-is-water-and-food-shortage

And Indigenous communities’ projects carry a message. The message is, “Look. It is possible to develop ways of life that protect the planet, that protect local economies, that protect the most vulnerable species, and they can bring life, peace, security and joy to the communities.” Because the future is communal. The future is ancestral, as we say. It’s the traditional forms of community life that are really going to save the planet. If it is in fact possible, at this point, to save the planet. Or rather, to save humanity.

Because, actually, as Ailton Krenak likes to say, it is humanity that is threatened by climate change. The planet will live on. It will undergo all these changes, and it will adapt. It will change, it will be transformed. But are we capable of adapting and transforming as quickly? We’re seeing that we’re not capable. With all these disasters happening, we’re just not. So Indigenous-led projects are very rich, because they come up with solutions that are both local and global.

External Link

Ailton Krenak: “Earth can leave us behind and go its own way” - UFRGS - Jornal da Universidade

MARIANA MARQUES

An important part of your work is rooted in garnering international visibility for Indigenous Peoples and building international alliances to strengthen the movement.

Would you say that a growing number of people are becoming aware of the struggles of Indigenous Peoples, and becoming allies, in Europe, for example? Is there increased recognition of the role that colonialism has played and continues to play in the lives of Indigenous communities?

EDSON KRENAK

One aspect of colonialism was the creation of laws, or public policies, or legislation, really, that could justify its actions. And what we see is that the European Union, for example, and blocs of countries at the geopolitical level, they create a lot of international mechanisms, international laws. And part of our job is to look at these laws, criticize these laws, and try to convince our allies, and the politicians here in Europe, to change these laws.

I’ll give you a very specific example, which is this new European Union directive on sustainability and business that deals with supply chain issues, and the raw materials supply chain. We fought very hard for them to put in place stronger mechanisms that can protect the environment and Indigenous Peoples. That can be done, for example, by forcing companies that do business outside of Europe to respect the rights of Indigenous communities to Free, Prior and Informed Consultation.

Because these consultations are a mechanism created by international law. Indigenous Peoples fought really hard to achieve this, to force companies and states to consult communities before establishing any project on their lands, in their territories. There was a big struggle, involving a lot of lobbying and discussions in the European Union, in the European Council, to try to prevent this consultation from being included in the final legislation. It ended up being mentioned in it. Is that a step forward? It is. But we wanted it to be in the actual text of that new directive, and also in the so-called Raw Materials Act, this new legislation, so that it would truly respect Indigenous Peoples and create stronger mechanisms to protect them.

External Link

The European Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive: Why Does It Matter for Indigenous Peoples?

So one of the things we’re doing is trying to convince people to become our allies, here in Europe. As a way to strengthen our advocacy work with these national and international legislative bodies here in Europe. But we also reach out to large companies. For example, car companies, and car factories that purchase minerals. Supermarket chains that purchase fruit. Pharmaceutical companies that get supplies from Brazil, and specifically from Indigenous communities and Indigenous territories. And we ask them to implement due diligence mechanisms.

We have had some success. It’s still not enough, but it’s important. Because it kind of allows us to get one foot in the door, and that is a source of hope for the future. That’s important. I’ve been collecting some positive, optimistic experiences when it comes to forging alliances here in Europe.

We have found that many organizations, and a large part of civil society, understand that Indigenous Peoples’ struggle is their struggle too. That it is a struggle for all of humanity, sharing the same boat, sailing in the same sea. And anything that happens to that boat, and on that sea, it will impact the whole world.

External Link

Urge the European Union to include Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) in its Critical Raw Materials Act

https://www.culturalsurvival.org/news/urge-european-union-include-free-prior-and-informed-consent-fpic-its-critical-raw-materials

MARIANA MARQUES