Connecting the Dots with Aby Sène-Harper

An enlightening conversation about the complex reality surrounding conservation in Africa, the movement to decolonize it, and the fundamental role Indigenous self-determination must play in the protection of nature.

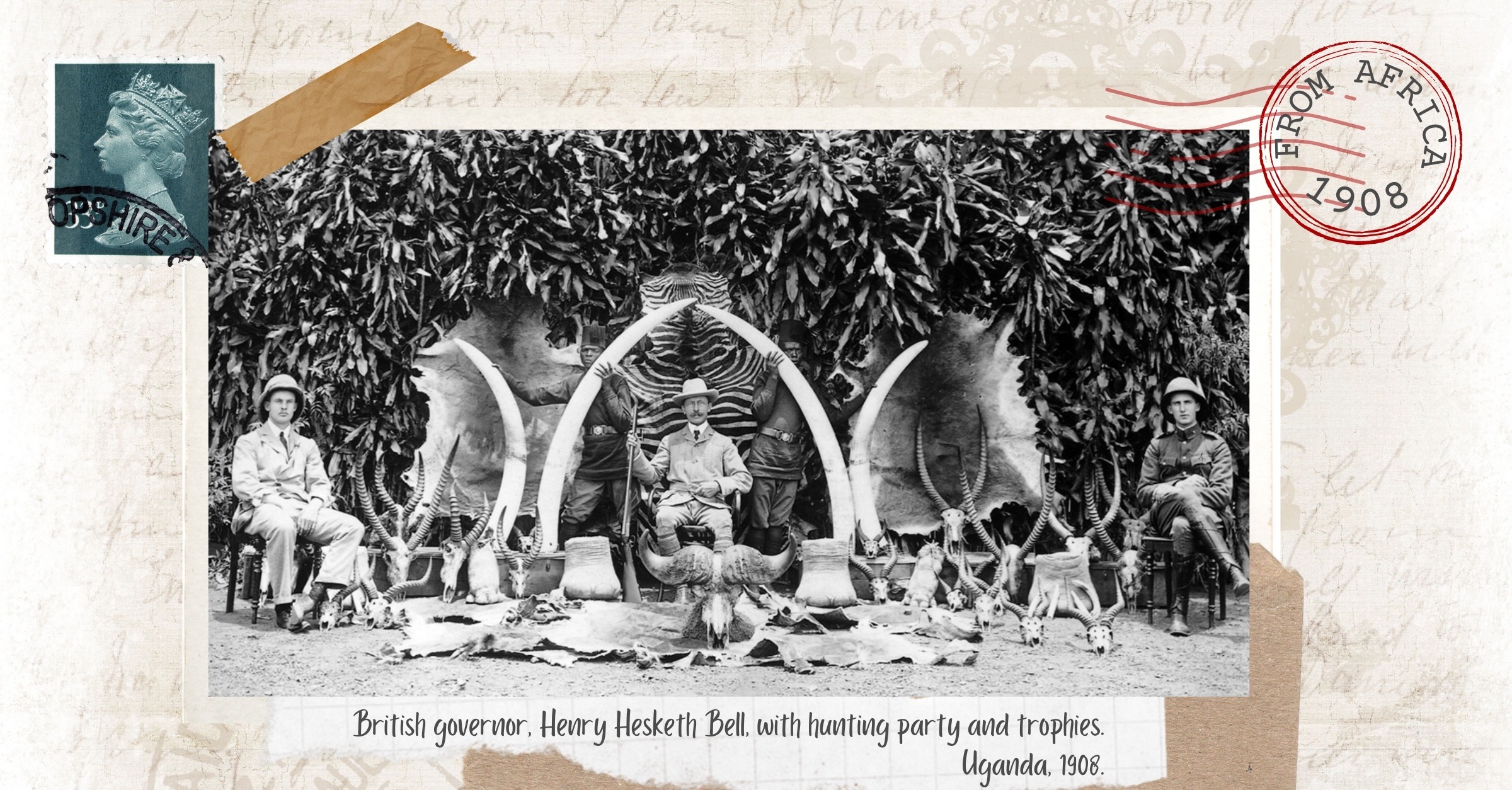

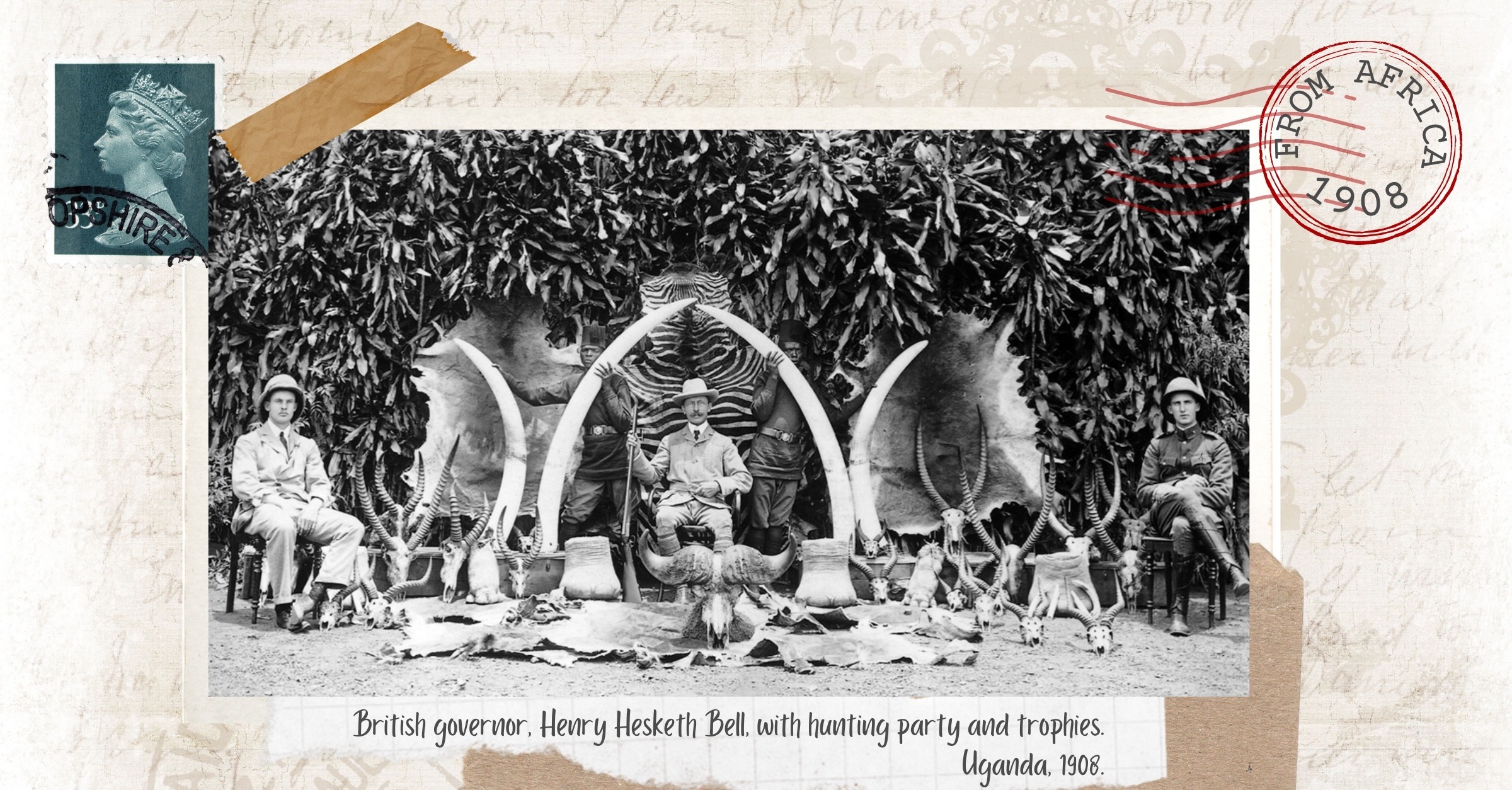

In a rapidly changing world, the urgency to protect nature is undeniable. However, there is an uncomfortable truth we must confront. The climate change and biodiversity crisis, largely caused by the West’s lifestyle and consumption patterns, disproportionately affects communities in Africa and all of the global South. And that’s not all. In the West, we often envision conservation through romanticized images of pristine natural landscapes inhabited by charismatic megafauna, leading to generous financial support for conservation organizations.

These conservation organizations often displace communities by creating pristine nature wildlife reserves or parks, and thus conservation refugees expelled from their ancestral lands. Ironically, it is these very communities that have conserved the areas through their lifestyles and ancestral knowledge of the land and ecosystems. Conservation is an exceedingly intricate reality, deeply entangled with the history of colonialism and the global capitalist market. Its geopolitical implications and impact on Indigenous and local communities should not be underestimated. While the concept of protected areas appears deceptively simple and universal, it masks a complex and at times violent and corrupt reality. Stripping away the powerful myth-making machine surrounding conservation requires a candid and unflinching gaze into its inner workings.

Guiding us on this journey to explore the path of decolonizing conservation is Dr. Aby Sène-Harper, a distinguished faculty member in Parks and Conservation Area Management at Clemson University, South Carolina. Her groundbreaking research delves into the intersections of parks and protected areas governance, livelihoods, nature-based tourism, and the relationship between race and nature. With her extensive writings on the colonial structures of power and conservation, Dr. Aby Sène-Harper has shed light on essential issues that demand our attention and action. We are eager for our listeners to join us in exploring her extraordinary work, as it inspires all to embark on a transformative journey towards decolonizing conservation.

Play the video version below (English subtitles available), or scroll down for the podcast version and the transcript.

CONNECTING THE DOTS – PODCAST

Are you a podcast fan? Make sure you subscribe to the podcast version of our Connecting the Dots series here.

ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT

MARIANA MARQUES (PRESIDENT, AZIMUTH WORLD FOUNDATION)

Could you share with us your journey into conservation, and how you began questioning mainstream ideas surrounding conservation in Africa?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

My journey into this work that I’m doing now, in biodiversity conservation, both in Africa but also in the US – in the US, focusing specifically on African American communities – it really started during my road trips growing up, throughout West Africa. Family road trips with my dad, my father and my sisters, my parents. I’m a national of Senegal, I was born in Senegal, but we lived in Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso and Ghana as well. So most of my trips were mostly concentrated in West Africa. And we visited several National Parks on all of those road trips. And that’s why I really begun taking a keen interest in biodiversity conservation in general, the idea of parks and protected areas, it was through those travels, visiting those National Parks.

While I had this notion of protecting biodiversity, I also did understand the centrality of how local communities actually cared for that land, and their deep connection with the wildlife, through a lot of those road trips that I was taking. The ways in which they were working the land, they cared for the land, the ways in which they also were able, for example, or had a deep knowledge of wildlife, using their own languages to describe wildlife movement, but also being able to predict seasonal patterns based on some of the wildlife that they were observing around them.

And those were my transformative years, where I started gaining an interest in both conservation, but also in development. It wasn’t just that I had a keen interest in Wildlife Conservation alone, but I also had a deep interest in rural development, having also witnessed some of the issues, the socioeconomic issues that some of these communities were facing or subjected to.

When I went to college, I was very much interested in understanding how can biodiversity conservation, or the preservation of our natural resources, also work as a catalyst for rural development, or developing some of those communities. And so that’s when I took on Environmental Economics as my major in college, and realized that economic models were not really capturing some of what I had experienced or even witnessed during those trips. So then I moved on to Eco-Tourism and Nature-based Tourism, for example. Because again, protected areas really stood out in my mind as a model for biodiversity conservation. This was really the journey that I had taken on, going into Parks and Protected Areas, a central piece to both leveraging biodiversity conservation, but also rural development. That is really the paradigm that I had bought into.

It wasn’t until I did my dissertation research in Senegal, or even prior to that, when I had observed, for example, conflicts between farmers. I will never forget one time when I lived in Ghana, where the newspaper came up and said the farmers are threatening to burn the National Park. And that was really an awakening moment into understanding what has driven these farmers, these villagers to want to burn the National Park, to burn the forest that was enclosing the National Park. What has driven this aversion towards this National Park? These are the people that have cared for the land, and now the complete flip to want to burn it. And this is when the question started to arise in my mind.

And realizing how conflictual the Western model of biodiversity conservation that has been imposed on the African continent, how in conflict it was with the African-centred or African models of biodiversity conservation. Those are two very divergent models, and this is when I really started exploring both of those paradigms, to see where the conflict arose.

MARIANA MARQUES

The post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, commonly known as 30×30, aims to set aside 30% of terrestrial cover for conservation by 2030. What are the implications of this initiative for Indigenous communities, and what’s at stake under the guise of biodiversity conservation?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

Plain and simple, the plan to expand the number, or to double, I should say, the coverage of protected area by 2030 will result in dispossession. That is the most fundamental concern that we have. There is going to be mass displacement.

We’ve already started seeing it, for example, with the Maasai community last year, who were threatened, who are currently facing massive eviction. It was about, I think, 70 to 80,000 Maasai people in the Loliondo and Ngorongoro conservation area. And the world has witnessed the violence of conservation then.

But the Maasai are not a unique case. I mean, they’re a classic case, but they’re not a unique case. Throughout the continent there are particularly pastoralists who are being either forced to sedentarize, but who are also losing grazing land in their ancestral land in the name of conservation. Fishers are also losing fishing grounds in the name of conservation, and farmers too, and hunters. These are Africans who have a deep connection to those lands, whose livelihoods are being threatened right now under the name of conservation.

What is very alarming to me is the pace at which it is going to happen. If we think about the first National Park or protected area, it was Yellowstone National Park, and that was in 1872, in the settler colony that is called the United States today, when Indigenous communities were forcibly removed to establish protected areas. That has opened up a wave of protected areas in much of the colonial world, further dispossessing communities. There has been an estimation that there were around 110 million people, Indigenous people, who have been displaced, Indigenous and local Native communities that have been displaced as a result of the establishment of protected areas. But that has been over 150 years. Now imagine trying to double that number within 10 years.

And the scale, the pace at which the dispossession is going to happen is very concerning. And it’s already resulting in Indigenous Rights violations. It’s already even resulting in Indigenous murders, murders of Indigenous and environmental activists. Global Witness has reported that in 2020, 200 indigenous environmental activists were murdered, from the global South. And all of those are related to wanting to fight for their, to retain the rights to those lands.

MARIANA MARQUES

Many conservation projects claim to be community-centered, incorporating community education and even participation. However, you’ve discussed the implications of Community-based Natural Resource Management and its impact on Indigenous self-determination. Can you share your insights and give us some examples?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

To really understand Community-based Natural Resources, the context of it all, it’s important to also place it historically, and what are really the major factors that led to the emergence of Community-based Natural Resources. And when I say Community-based Natural Resources, it’s the same as Community-based Conservation or Conservancies, as they call it as well. So there are different iterations, but basically Community-based Natural Resources Management or Community-based Conservation, which I will call CBC from here on now, hereafter, it’s that it gives a space for the local community to manage conservation projects. And there are different ways to do that. Or not only to manage conservation projects, but also to be able to benefit economically from conservation projects.

CBC projects really started to emerge because of two global factors. First, it was really the backlash against fortress conservation. That fortress conservation leads to further impoverishment. Fortress conservation is also dispossessing local communities, but it’s also really severing their ties to their ancestral land. And it has also resulted in backlash, in terms of retaliation by local communities, as I had to explain with that anecdote earlier, when the farmers had threatened to burn the National Park. And so it became very counterproductive. But it was also because of Indigenous resistance too, against fortress conservation, throughout the 70s, 80s, and so on. And so that was one push towards Community-based Conservation or Community-based Natural Resources Management.

But the second factor was also the realization that Indigenous communities also play a critical role, or I should even say fundamental, to biodiversity conservation. Through their livelihood practices, but also their spirituality. We’re finally recognizing that Indigenous communities are the reason why these landscapes were so well preserved, through their own customary, their own Indigenous natural resource management systems.

It was the Rio de Janeiro UN Environmental Summit in 1992 that actually gave a greater space into the conservation discourse for Indigenous communities. It was against the backdrop of that declaration, the UN Declaration of 1992, that CBC started to proliferate throughout Africa. And not just in Africa, but even in Latin America, in Asia.

And what often happened was that there were some institutional reforms in Protected Area governance, in National Parks governance, that created community-based organizations at the local level, and this community-based organizations were in charge of representing the interests of the community in the decision-making process of how those resources should be managed. So that’s one institutional aspect of it. The second aspect was that conservation projects, but also governments, had to work together to create economic activities that would benefit local communities. This is when tourism became key, really started to gain a foothold in conservation. They started selling community-based tourism projects around National Parks, saying, “This community-based conservation project benefits local communities, and it also serves to protect the wildlife as well.”

Now, everything that I have described so far is around economic benefit, and also institutional reform. One thing that was thoroughly missing in the discourse was also self-determination for Indigenous communities. Indigenous communities were very clear from the beginning that what they wanted was self-determination, the right to be able to benefit from those conservation projects, but also be able to determine what activities they were able to take on, on those lands. But what Community-based Natural Resources Management does is, “Sure, what we will do is create an institution, to represent, to be the voice of the community. But we are going to tell you what kind of activities you can take on, on those lands, still.” So there is no self-determination there, there is no sovereignty.

And so while Community-based Conservation was a progress towards including Indigenous voices into those spaces, it actually had not responded to the demands of Indigenous communities for sovereignty and self-determination. Being able to get that land back, and being able to exercise their traditional rights, their birthrights of exercising those customary resource management systems, that have actually preserved the land. Community-based conservation, how they were able to benefit from it, was imposed by international conservation agencies.

MARIANA MARQUES

You’ve said that sensational images can create misperceptions about land thefts and conservation. What are the best ways and platforms to advance the discourse on decolonizing conservation? And what actions can people actually take to contribute to this movement?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

In my piece that is published in The Republic, “Against Wildlife Republics”, and The Republic is a pan-African review that is based in Nigeria, in there I talk about the danger of seeing the Maasai case… Or I shouldn’t say the danger. It’s very real, the violence against the Maasai is real, is wrong. And so it deserved to be exposed, absolutely. What I was trying to explain is that it could, however, lead to the misperception that the violence had to be sensational and direct, in order to create the same outcomes of dispossession.

So the military shows up, as we have seen in the Maasai case, and started to forcibly evict them. That was really a last resort. That was the last resort, because the Maasai community have really put up a resistance upfront for a very, very long time. What I was trying to explain is that we need to also pay attention to those instances where evictions are not as violent as what we have seen in the case of the Maasai.

What usually happens is that there is the rewriting of environmental laws over time. There are different ways. You either rewrite environmental laws to actually be able to forcibly evict them. Or what I call manufactured consent is state-sanctioned deprivation of those communities. What the state can do is either withdraw public services, like schools, hospitals, water, for example. They create the conditions of impoverishment, so that it’s easier for communities to accept the relocation. You’re basically manufacturing consent. And then they label it as “voluntary relocation.” And that’s what happens in a lot of cases, too.

‘m seeing it, for example, in the Casamance region, in Senegal, where there are talks around carbon offset projects as well – which is a different form of conservation, it’s all the same predatory practices – where people are conceding to carbon offset projects because it is the only alternative they have. These communities are extremely impoverished. The schools are in poor conditions, the hospitals are in poor conditions. And when you have a private actor, someone like Shell, for example, Shell Oil, or BP, that comes in and says, “We want a carbon offset project with you, or a biodiversity offset project with you. We’ll give you this much money,” you have no other choice but to say, “Well, we’ll buy onto that project.” Even though it seems very nebulous, they have no other choice, because it’s the better alternative. Even if it’s not a good alternative, it’s the better one. And that’s what happens often in a lot of these cases.

What I was trying to explain by using “sensationalizing” is the violence doesn’t have to be sensational for it to produce the same violent outcomes over time.

MARIANA MARQUES

There’s an often-overlooked connection between Protected Areas and global extractive projects. Can you help us understand this link and its lack of transparency?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

Something that is often overlooked is how Protected Areas have actually become sites of extraction. The narrative at the beginning was that Protected Areas are actually the solution to extraction, or are the opposite of extraction. You take land, you put it aside, and there’s no extraction happening there. Which is actually a myth, because extraction still happens in Protected Areas.

On the contrary, biodiversity conservation, wildlife conservation, is just a guise for further extraction. It’s a guise to be able to dispossess local communities, without any public scrutiny. Because really, who wants to fight protecting nature? It gives them a moral high ground to be able to give social license to the dispossession of local communities. But then, somewhere, 5, 10, 20 years down the road, they’re able to give private concessions to extractive industries to be able to extract on those lands.

I talk about extraction, what kind of extraction? You have logging happening in Protected Areas, you have mining happening in Protected Areas. The Rainforest Foundation’s “Mapping for Rights” project, they are mapping right now all the private concessions that have been given to extractive industries within those places in central Africa. I really encourage everyone, your listeners, to take a look at it. It’s the Rainforest Foundation’s “Mapping for Rights” project. But not just there, not just in central Africa. I give the example in Senegal, where there’s a lot of mining also happening in Niokolo-Koba by Petowal Mining Industry within the park, in Niokolo-Koba National Park.

There is mining, there’s logging, but there is also the declassification of Protected Areas, or part of it anyway, to be able to give it to agribusinesses. There is currently a battle at Ndiael Wildlife Refuge in the north of Senegal, where the government has degazetted in 2018 about 2000 hectares of land from there, to give it to an agribusiness (I think it’s an Italian agribusiness, Senhuile), to be able to have a plantation in that area, to farm that land which was a Protected Area, when there are still active land claims by the local community, to be able to get that land back.

Protected Areas now have just become, really, an excuse to dispossess local communities, and then place it under the auspices of the extractive industry, but also under the auspices of all these African governments that are later on, down the line, going to sell that land to the highest bidder. And that’s what’s happening too, with carbon offset markets or biodiversity offset. The buyers of carbon offset projects are extractive industries.

MARIANA MARQUES

Protected Areas are being integrated into the global carbon markets. What are the actual results, in terms of halting emissions, deforestation, biodiversity loss and pollution?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

Carbon offset is basically a global extractive project. There is carbon and there is biodiversity offset projects. Plain and simple, it legitimizes the plundering of nature. That’s it. It legitimizes the ecological destruction of the planet. The idea is, “You can pollute here, you can extract here, as long as you go here and protect this land, or plant so many forests, or so many trees. And then that will offset whatever destruction you’ve done on this side.” And who are the highest bidders for those? Obviously, they’re the extractive projects.

Right now, in Senegal, Shell, BP, Petowal are all on board with buying carbon projects in the South of Senegal, on the mangroves, with the understanding that they are able to mine for gas, to completely deregulate too. It also gives them the green light to be able to take on ecologically destructive practices. And so it only accelerates, it doesn’t resolve the issue, because you are not stopping the ecological destruction. On the contrary, you are legitimizing it, by later on saving forests on this side.

But even the economic models that they are using in carbon offset, actually the science that they’re using to show that that forest is actually offsetting the amount of pollution, is completely bogus, it has been completely debunked. No amount of offset is going to completely offset how much pollution, how much destruction has already been happening. And so that’s one.

But two, you are also, through this carbon offset project or this biodiversity offset project, you are dispossessing, you are actually removing the very people who have spent centuries protecting that land. It is not accidental that the lands that are now targeted for Protected Areas are the very lands that have been under the care, the stewardship of Indigenous people. It is precisely because they have cared for that land, that these lands are now some of the most biodiverse. You are creating, or you are fixing, a problem that does not exist on that land in the first place. These people are there to protect the land, why are you removing them from that land?

And all of that under the guise of conservation, but also all of that to further cede land for carbon offsets, so that the global north, or all of these extractive projects, can continue the plunder of nature elsewhere. It solves no problem at all. If anything, it further accelerates deforestation. It also accelerates pollution, and it continues the violence against Indigenous communities. And so the best way really to protect those lands is to really, really fight for Indigenous sovereignty on those lands. That is plain and simple. There is no other way. If conservation projects or if environmental projects are not centering the issue of Indigenous sovereignty, then they are not working towards conservation.

MARIANA MARQUES

And as an academic, are there robust groups of researchers working towards decolonizing conservation? Or is it still a quite lonely pursuit?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

I would say that it’s actually growing. Let me say this: in Conservation, Wildlife Conservation itself, it’s still a lonely pursuit. But there are others outside of Wildlife Conservation, who are actually understanding how colonial still Wildlife Conservation is. And I’ve had to really go in those spaces outside of Wildlife Conservation to be able to make those connections. But in our field, in Wildlife, in Biodiversity Conservation, it’s still a bit lonely, in a way.

But still, the number of researchers recently that have contacted me, who are actually young, a lot of them are doctoral students who have contacted me as a result of reading my work, have been very, very encouraging. But in academia, still very much it can be very lonely. But other foundations like yours, for example, outside of academia, I think it’s where I have found the most fulfilling connections that I have made. In that space, in the decolonizing conservation space.

MARIANA MARQUES

What is your vision for a future of just, decolonized conservation? Do you think it’s achievable? Would you say that guaranteeing Indigenous sovereignty is an essential first step in that direction?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

There is no question around it. I think that the question of Indigenous sovereignty, of sovereignty over how to govern natural resources, how to benefit from natural resources, must be front and center. Indigenous, but also local communities as well. I know there’s a lot of confounding of Indigenous and local communities, but there are also political tensions around that word. But I’m going to use Indigenous and local communities just as a political umbrella. But the sovereignty of governance over natural resources must be front and center.

And then, after that, what comes after that? That is, how do you create the conditions under which that sovereignty becomes sustainable? Because we can talk about landback, and we have seen it, we have seen land restitution to local communities who ended up selling that land because of impoverishment, too. How do we also create the conditions under which that sovereignty remains? And that is also understanding how you improve the material conditions of Indigenous communities. So that later, when a predatory threat, when a threat is coming in, or private interests are coming in, they are able to better negotiate the terms of that sharing of land, if possible, if it can happen at all. But also what kind of activities can be done on their land, rather than forcibly, or having no other choice but to sell that land, because they don’t have any other opportunities or economic opportunities.

One thing is also completely decentering Protected Areas as a primary mode of conservation. Protected Areas, in a sense that is completely devoid of humans. Indigenous communities, on their land, they have for a long time cared for sacred forests, sacred mangroves. Again, thinking about the Diola people in southern Casamance, who through their spiritual practices have created their own protected areas. The sacred mangroves of Casamance are a perfect example, and there are tons of sacred spaces in there, too. So, Indigenous sovereignty, yes. Improving the material condition of Indigenous communities. But decentering, first and foremost, the Western model of conservation that has no vision for culture or humans within those protected areas. And recentering Indigenous worldviews into Biodiversity Conservation.

External Link

Against Wildlife Republics by Aby Sène-Harper | The Republic

https://republic.com.ng/october-november-2022/conservation-and-imperialist-expansion-in-africa/

Western Nonprofits Are Trampling Over Africans' Rights and Land by Aby Sène | Foreign Policy

Land grabs and conservation propaganda by Aby Sène | Africa Is a Country

Connecting the Dots with Aby Sène-Harper

An enlightening conversation about the complex reality surrounding conservation in Africa, the movement to decolonize it, and the fundamental role Indigenous self-determination must play in the protection of nature.

In a rapidly changing world, the urgency to protect nature is undeniable. However, there is an uncomfortable truth we must confront. The climate change and biodiversity crisis, largely caused by the West’s lifestyle and consumption patterns, disproportionately affects communities in Africa and all of the global South. And that’s not all. In the West, we often envision conservation through romanticized images of pristine natural landscapes inhabited by charismatic megafauna, leading to generous financial support for conservation organizations.

These conservation organizations often displace communities by creating pristine nature wildlife reserves or parks, and thus conservation refugees expelled from their ancestral lands. Ironically, it is these very communities that have conserved the areas through their lifestyles and ancestral knowledge of the land and ecosystems. Conservation is an exceedingly intricate reality, deeply entangled with the history of colonialism and the global capitalist market. Its geopolitical implications and impact on Indigenous and local communities should not be underestimated. While the concept of protected areas appears deceptively simple and universal, it masks a complex and at times violent and corrupt reality. Stripping away the powerful myth-making machine surrounding conservation requires a candid and unflinching gaze into its inner workings.

Guiding us on this journey to explore the path of decolonizing conservation is Dr. Aby Sène-Harper, a distinguished faculty member in Parks and Conservation Area Management at Clemson University, South Carolina. Her groundbreaking research delves into the intersections of parks and protected areas governance, livelihoods, nature-based tourism, and the relationship between race and nature. With her extensive writings on the colonial structures of power and conservation, Dr. Aby Sène-Harper has shed light on essential issues that demand our attention and action. We are eager for our listeners to join us in exploring her extraordinary work, as it inspires all to embark on a transformative journey towards decolonizing conservation.

Play the video version below (English subtitles available), or scroll down for the podcast version and the transcript.

CONNECTING THE DOTS – PODCAST

Are you a podcast fan? Make sure you subscribe to the podcast version of our Connecting the Dots series here.

ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT

MARIANA MARQUES (PRESIDENT, AZIMUTH WORLD FOUNDATION)

Could you share with us your journey into conservation, and how you began questioning mainstream ideas surrounding conservation in Africa?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

My journey into this work that I’m doing now, in biodiversity conservation, both in Africa but also in the US – in the US, focusing specifically on African American communities – it really started during my road trips growing up, throughout West Africa. Family road trips with my dad, my father and my sisters, my parents. I’m a national of Senegal, I was born in Senegal, but we lived in Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso and Ghana as well. So most of my trips were mostly concentrated in West Africa. And we visited several National Parks on all of those road trips. And that’s why I really begun taking a keen interest in biodiversity conservation in general, the idea of parks and protected areas, it was through those travels, visiting those National Parks.

While I had this notion of protecting biodiversity, I also did understand the centrality of how local communities actually cared for that land, and their deep connection with the wildlife, through a lot of those road trips that I was taking. The ways in which they were working the land, they cared for the land, the ways in which they also were able, for example, or had a deep knowledge of wildlife, using their own languages to describe wildlife movement, but also being able to predict seasonal patterns based on some of the wildlife that they were observing around them.

And those were my transformative years, where I started gaining an interest in both conservation, but also in development. It wasn’t just that I had a keen interest in Wildlife Conservation alone, but I also had a deep interest in rural development, having also witnessed some of the issues, the socioeconomic issues that some of these communities were facing or subjected to.

When I went to college, I was very much interested in understanding how can biodiversity conservation, or the preservation of our natural resources, also work as a catalyst for rural development, or developing some of those communities. And so that’s when I took on Environmental Economics as my major in college, and realized that economic models were not really capturing some of what I had experienced or even witnessed during those trips. So then I moved on to Eco-Tourism and Nature-based Tourism, for example. Because again, protected areas really stood out in my mind as a model for biodiversity conservation. This was really the journey that I had taken on, going into Parks and Protected Areas, a central piece to both leveraging biodiversity conservation, but also rural development. That is really the paradigm that I had bought into.

It wasn’t until I did my dissertation research in Senegal, or even prior to that, when I had observed, for example, conflicts between farmers. I will never forget one time when I lived in Ghana, where the newspaper came up and said the farmers are threatening to burn the National Park. And that was really an awakening moment into understanding what has driven these farmers, these villagers to want to burn the National Park, to burn the forest that was enclosing the National Park. What has driven this aversion towards this National Park? These are the people that have cared for the land, and now the complete flip to want to burn it. And this is when the question started to arise in my mind.

And realizing how conflictual the Western model of biodiversity conservation that has been imposed on the African continent, how in conflict it was with the African-centred or African models of biodiversity conservation. Those are two very divergent models, and this is when I really started exploring both of those paradigms, to see where the conflict arose.

MARIANA MARQUES

The post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, commonly known as 30×30, aims to set aside 30% of terrestrial cover for conservation by 2030. What are the implications of this initiative for Indigenous communities, and what’s at stake under the guise of biodiversity conservation?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

Plain and simple, the plan to expand the number, or to double, I should say, the coverage of protected area by 2030 will result in dispossession. That is the most fundamental concern that we have. There is going to be mass displacement.

We’ve already started seeing it, for example, with the Maasai community last year, who were threatened, who are currently facing massive eviction. It was about, I think, 70 to 80,000 Maasai people in the Loliondo and Ngorongoro conservation area. And the world has witnessed the violence of conservation then.

But the Maasai are not a unique case. I mean, they’re a classic case, but they’re not a unique case. Throughout the continent there are particularly pastoralists who are being either forced to sedentarize, but who are also losing grazing land in their ancestral land in the name of conservation. Fishers are also losing fishing grounds in the name of conservation, and farmers too, and hunters. These are Africans who have a deep connection to those lands, whose livelihoods are being threatened right now under the name of conservation.

What is very alarming to me is the pace at which it is going to happen. If we think about the first National Park or protected area, it was Yellowstone National Park, and that was in 1872, in the settler colony that is called the United States today, when Indigenous communities were forcibly removed to establish protected areas. That has opened up a wave of protected areas in much of the colonial world, further dispossessing communities. There has been an estimation that there were around 110 million people, Indigenous people, who have been displaced, Indigenous and local Native communities that have been displaced as a result of the establishment of protected areas. But that has been over 150 years. Now imagine trying to double that number within 10 years.

And the scale, the pace at which the dispossession is going to happen is very concerning. And it’s already resulting in Indigenous Rights violations. It’s already even resulting in Indigenous murders, murders of Indigenous and environmental activists. Global Witness has reported that in 2020, 200 indigenous environmental activists were murdered, from the global South. And all of those are related to wanting to fight for their, to retain the rights to those lands.

MARIANA MARQUES

Many conservation projects claim to be community-centered, incorporating community education and even participation. However, you’ve discussed the implications of Community-based Natural Resource Management and its impact on Indigenous self-determination. Can you share your insights and give us some examples?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

To really understand Community-based Natural Resources, the context of it all, it’s important to also place it historically, and what are really the major factors that led to the emergence of Community-based Natural Resources. And when I say Community-based Natural Resources, it’s the same as Community-based Conservation or Conservancies, as they call it as well. So there are different iterations, but basically Community-based Natural Resources Management or Community-based Conservation, which I will call CBC from here on now, hereafter, it’s that it gives a space for the local community to manage conservation projects. And there are different ways to do that. Or not only to manage conservation projects, but also to be able to benefit economically from conservation projects.

CBC projects really started to emerge because of two global factors. First, it was really the backlash against fortress conservation. That fortress conservation leads to further impoverishment. Fortress conservation is also dispossessing local communities, but it’s also really severing their ties to their ancestral land. And it has also resulted in backlash, in terms of retaliation by local communities, as I had to explain with that anecdote earlier, when the farmers had threatened to burn the National Park. And so it became very counterproductive. But it was also because of Indigenous resistance too, against fortress conservation, throughout the 70s, 80s, and so on. And so that was one push towards Community-based Conservation or Community-based Natural Resources Management.

But the second factor was also the realization that Indigenous communities also play a critical role, or I should even say fundamental, to biodiversity conservation. Through their livelihood practices, but also their spirituality. We’re finally recognizing that Indigenous communities are the reason why these landscapes were so well preserved, through their own customary, their own Indigenous natural resource management systems.

It was the Rio de Janeiro UN Environmental Summit in 1992 that actually gave a greater space into the conservation discourse for Indigenous communities. It was against the backdrop of that declaration, the UN Declaration of 1992, that CBC started to proliferate throughout Africa. And not just in Africa, but even in Latin America, in Asia.

And what often happened was that there were some institutional reforms in Protected Area governance, in National Parks governance, that created community-based organizations at the local level, and this community-based organizations were in charge of representing the interests of the community in the decision-making process of how those resources should be managed. So that’s one institutional aspect of it. The second aspect was that conservation projects, but also governments, had to work together to create economic activities that would benefit local communities. This is when tourism became key, really started to gain a foothold in conservation. They started selling community-based tourism projects around National Parks, saying, “This community-based conservation project benefits local communities, and it also serves to protect the wildlife as well.”

Now, everything that I have described so far is around economic benefit, and also institutional reform. One thing that was thoroughly missing in the discourse was also self-determination for Indigenous communities. Indigenous communities were very clear from the beginning that what they wanted was self-determination, the right to be able to benefit from those conservation projects, but also be able to determine what activities they were able to take on, on those lands. But what Community-based Natural Resources Management does is, “Sure, what we will do is create an institution, to represent, to be the voice of the community. But we are going to tell you what kind of activities you can take on, on those lands, still.” So there is no self-determination there, there is no sovereignty.

And so while Community-based Conservation was a progress towards including Indigenous voices into those spaces, it actually had not responded to the demands of Indigenous communities for sovereignty and self-determination. Being able to get that land back, and being able to exercise their traditional rights, their birthrights of exercising those customary resource management systems, that have actually preserved the land. Community-based conservation, how they were able to benefit from it, was imposed by international conservation agencies.

MARIANA MARQUES

You’ve said that sensational images can create misperceptions about land thefts and conservation. What are the best ways and platforms to advance the discourse on decolonizing conservation? And what actions can people actually take to contribute to this movement?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

In my piece that is published in The Republic, “Against Wildlife Republics”, and The Republic is a pan-African review that is based in Nigeria, in there I talk about the danger of seeing the Maasai case… Or I shouldn’t say the danger. It’s very real, the violence against the Maasai is real, is wrong. And so it deserved to be exposed, absolutely. What I was trying to explain is that it could, however, lead to the misperception that the violence had to be sensational and direct, in order to create the same outcomes of dispossession.

So the military shows up, as we have seen in the Maasai case, and started to forcibly evict them. That was really a last resort. That was the last resort, because the Maasai community have really put up a resistance upfront for a very, very long time. What I was trying to explain is that we need to also pay attention to those instances where evictions are not as violent as what we have seen in the case of the Maasai.

What usually happens is that there is the rewriting of environmental laws over time. There are different ways. You either rewrite environmental laws to actually be able to forcibly evict them. Or what I call manufactured consent is state-sanctioned deprivation of those communities. What the state can do is either withdraw public services, like schools, hospitals, water, for example. They create the conditions of impoverishment, so that it’s easier for communities to accept the relocation. You’re basically manufacturing consent. And then they label it as “voluntary relocation.” And that’s what happens in a lot of cases, too.

‘m seeing it, for example, in the Casamance region, in Senegal, where there are talks around carbon offset projects as well – which is a different form of conservation, it’s all the same predatory practices – where people are conceding to carbon offset projects because it is the only alternative they have. These communities are extremely impoverished. The schools are in poor conditions, the hospitals are in poor conditions. And when you have a private actor, someone like Shell, for example, Shell Oil, or BP, that comes in and says, “We want a carbon offset project with you, or a biodiversity offset project with you. We’ll give you this much money,” you have no other choice but to say, “Well, we’ll buy onto that project.” Even though it seems very nebulous, they have no other choice, because it’s the better alternative. Even if it’s not a good alternative, it’s the better one. And that’s what happens often in a lot of these cases.

What I was trying to explain by using “sensationalizing” is the violence doesn’t have to be sensational for it to produce the same violent outcomes over time.

MARIANA MARQUES

There’s an often-overlooked connection between Protected Areas and global extractive projects. Can you help us understand this link and its lack of transparency?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

Something that is often overlooked is how Protected Areas have actually become sites of extraction. The narrative at the beginning was that Protected Areas are actually the solution to extraction, or are the opposite of extraction. You take land, you put it aside, and there’s no extraction happening there. Which is actually a myth, because extraction still happens in Protected Areas.

On the contrary, biodiversity conservation, wildlife conservation, is just a guise for further extraction. It’s a guise to be able to dispossess local communities, without any public scrutiny. Because really, who wants to fight protecting nature? It gives them a moral high ground to be able to give social license to the dispossession of local communities. But then, somewhere, 5, 10, 20 years down the road, they’re able to give private concessions to extractive industries to be able to extract on those lands.

I talk about extraction, what kind of extraction? You have logging happening in Protected Areas, you have mining happening in Protected Areas. The Rainforest Foundation’s “Mapping for Rights” project, they are mapping right now all the private concessions that have been given to extractive industries within those places in central Africa. I really encourage everyone, your listeners, to take a look at it. It’s the Rainforest Foundation’s “Mapping for Rights” project. But not just there, not just in central Africa. I give the example in Senegal, where there’s a lot of mining also happening in Niokolo-Koba by Petowal Mining Industry within the park, in Niokolo-Koba National Park.

There is mining, there’s logging, but there is also the declassification of Protected Areas, or part of it anyway, to be able to give it to agribusinesses. There is currently a battle at Ndiael Wildlife Refuge in the north of Senegal, where the government has degazetted in 2018 about 2000 hectares of land from there, to give it to an agribusiness (I think it’s an Italian agribusiness, Senhuile), to be able to have a plantation in that area, to farm that land which was a Protected Area, when there are still active land claims by the local community, to be able to get that land back.

Protected Areas now have just become, really, an excuse to dispossess local communities, and then place it under the auspices of the extractive industry, but also under the auspices of all these African governments that are later on, down the line, going to sell that land to the highest bidder. And that’s what’s happening too, with carbon offset markets or biodiversity offset. The buyers of carbon offset projects are extractive industries.

MARIANA MARQUES

Protected Areas are being integrated into the global carbon markets. What are the actual results, in terms of halting emissions, deforestation, biodiversity loss and pollution?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

Carbon offset is basically a global extractive project. There is carbon and there is biodiversity offset projects. Plain and simple, it legitimizes the plundering of nature. That’s it. It legitimizes the ecological destruction of the planet. The idea is, “You can pollute here, you can extract here, as long as you go here and protect this land, or plant so many forests, or so many trees. And then that will offset whatever destruction you’ve done on this side.” And who are the highest bidders for those? Obviously, they’re the extractive projects.

Right now, in Senegal, Shell, BP, Petowal are all on board with buying carbon projects in the South of Senegal, on the mangroves, with the understanding that they are able to mine for gas, to completely deregulate too. It also gives them the green light to be able to take on ecologically destructive practices. And so it only accelerates, it doesn’t resolve the issue, because you are not stopping the ecological destruction. On the contrary, you are legitimizing it, by later on saving forests on this side.

But even the economic models that they are using in carbon offset, actually the science that they’re using to show that that forest is actually offsetting the amount of pollution, is completely bogus, it has been completely debunked. No amount of offset is going to completely offset how much pollution, how much destruction has already been happening. And so that’s one.

But two, you are also, through this carbon offset project or this biodiversity offset project, you are dispossessing, you are actually removing the very people who have spent centuries protecting that land. It is not accidental that the lands that are now targeted for Protected Areas are the very lands that have been under the care, the stewardship of Indigenous people. It is precisely because they have cared for that land, that these lands are now some of the most biodiverse. You are creating, or you are fixing, a problem that does not exist on that land in the first place. These people are there to protect the land, why are you removing them from that land?

And all of that under the guise of conservation, but also all of that to further cede land for carbon offsets, so that the global north, or all of these extractive projects, can continue the plunder of nature elsewhere. It solves no problem at all. If anything, it further accelerates deforestation. It also accelerates pollution, and it continues the violence against Indigenous communities. And so the best way really to protect those lands is to really, really fight for Indigenous sovereignty on those lands. That is plain and simple. There is no other way. If conservation projects or if environmental projects are not centering the issue of Indigenous sovereignty, then they are not working towards conservation.

MARIANA MARQUES

And as an academic, are there robust groups of researchers working towards decolonizing conservation? Or is it still a quite lonely pursuit?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

I would say that it’s actually growing. Let me say this: in Conservation, Wildlife Conservation itself, it’s still a lonely pursuit. But there are others outside of Wildlife Conservation, who are actually understanding how colonial still Wildlife Conservation is. And I’ve had to really go in those spaces outside of Wildlife Conservation to be able to make those connections. But in our field, in Wildlife, in Biodiversity Conservation, it’s still a bit lonely, in a way.

But still, the number of researchers recently that have contacted me, who are actually young, a lot of them are doctoral students who have contacted me as a result of reading my work, have been very, very encouraging. But in academia, still very much it can be very lonely. But other foundations like yours, for example, outside of academia, I think it’s where I have found the most fulfilling connections that I have made. In that space, in the decolonizing conservation space.

MARIANA MARQUES

What is your vision for a future of just, decolonized conservation? Do you think it’s achievable? Would you say that guaranteeing Indigenous sovereignty is an essential first step in that direction?

ABY SÈNE-HARPER

There is no question around it. I think that the question of Indigenous sovereignty, of sovereignty over how to govern natural resources, how to benefit from natural resources, must be front and center. Indigenous, but also local communities as well. I know there’s a lot of confounding of Indigenous and local communities, but there are also political tensions around that word. But I’m going to use Indigenous and local communities just as a political umbrella. But the sovereignty of governance over natural resources must be front and center.

And then, after that, what comes after that? That is, how do you create the conditions under which that sovereignty becomes sustainable? Because we can talk about landback, and we have seen it, we have seen land restitution to local communities who ended up selling that land because of impoverishment, too. How do we also create the conditions under which that sovereignty remains? And that is also understanding how you improve the material conditions of Indigenous communities. So that later, when a predatory threat, when a threat is coming in, or private interests are coming in, they are able to better negotiate the terms of that sharing of land, if possible, if it can happen at all. But also what kind of activities can be done on their land, rather than forcibly, or having no other choice but to sell that land, because they don’t have any other opportunities or economic opportunities.

One thing is also completely decentering Protected Areas as a primary mode of conservation. Protected Areas, in a sense that is completely devoid of humans. Indigenous communities, on their land, they have for a long time cared for sacred forests, sacred mangroves. Again, thinking about the Diola people in southern Casamance, who through their spiritual practices have created their own protected areas. The sacred mangroves of Casamance are a perfect example, and there are tons of sacred spaces in there, too. So, Indigenous sovereignty, yes. Improving the material condition of Indigenous communities. But decentering, first and foremost, the Western model of conservation that has no vision for culture or humans within those protected areas. And recentering Indigenous worldviews into Biodiversity Conservation.

External Link

Against Wildlife Republics by Aby Sène-Harper | The Republic

https://republic.com.ng/october-november-2022/conservation-and-imperialist-expansion-in-africa/

Western Nonprofits Are Trampling Over Africans' Rights and Land by Aby Sène | Foreign Policy