Connecting the Dots with Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

CtD_UDCB_PostCover.001

Village of Covas do Barroso, northern Portugal

Fighting against a large-scale lithium mining project, a community in northern Portugal defends its sustainable farming practices and the World Agricultural Heritage Site they’ve called home for generations

For this episode of Connecting the Dots, we bring you a conversation recorded in Covas do Barroso, in northern Portugal, during the annual resistance camp against lithium mining.

This small mountain village, recognized by the FAO as a World Agricultural Heritage Site, faces plans for one of Europe’s largest open-pit lithium mines. A mine that threatens to destroy 2,000 hectares of community land, contaminate the waters of the Covas River—a tributary of the Douro river—and displace a community that has lived self-sufficiently for generations.

We hear from Aida Fernandes (local farmer), Catarina Alves Scarrott (born in Covas, and currently a teacher in London) and Mariana Riquito (researcher), all members of the local, grassroots association Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso (UDCB).

Follow UDCB’s work at their official website, or through their official Instagram and Facebook accounts.

If you’re in the United States, you can find ways to support this cause and to get involved at savebarroso.com – the official website of Americans for the Conservation of Barroso Portugal, a US-based 501(c)(3) organization.

Play the video version below (English subtitles available), or scroll down for the podcast version (dubbed in English) and for the transcript (in English).

CONNECTING THE DOTS – PODCAST

Are you a podcast fan? Make sure you subscribe to the podcast version of our Connecting the Dots series here.

ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT (TRANSLATION)

43662679_339503800133100_4064701076920598528_n

Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

AIDA FERNANDES (LOCAL FARMER, MEMBER OF UDCB)

Covas do Barroso is a predominantly agricultural village. People make their living from farming and sheep husbandry. I myself am a farmer, I own cows, and I make my living from farming.

And Covas do Barroso is a unique place. Because it has characteristics that make us basically self-sufficient. We are able to produce everything we need for our day-to-day lives, from olive oil to vegetables, meat, fruit, and fish from our river.

So I think this is a great asset, and it’s a privilege to be able to live like this, in a place where we have fresh air, clean water, and lots of greenery.

120540483_846408832775925_706895992404984681_n

Aida Fernandes | Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

In May 2017, suspicious movements began on the surrounding area. An old 2006 license for quartz and feldspar mining was being used for something very different—and much bigger.

AIDA FERNANDES

There had been a quartz and feldspar quarry since 2006, which had never been used. In May 2017, there was some activity taking place in the area. I remember asking one of the workers what they were doing. She said, “Oh, just some work.” Summer is a busy time for us here. We are like ants, gathering in the summer, so we have enough for the winter. People are focused on their tasks and don’t pay much attention to anything else.

A month later, Catarina called me from London to ask me what was going on in Covas. When she called me, I just replied, “Nothing’s going on. It’s very hot and we’re very busy.” And she said, “But I’m reading here that the largest open-pit mine will be installed in Covas do Barroso.”

I didn’t even know what lithium was, I admit. And then when she began describing what this process involved, that unlike the quarry that was there now, the new project would also include a washing plant, and when she described how big it would be, it was a shock, it was scary. “That’s impossible, that can’t be true. No way. How can they plan something like this without even informing us?”

49564077_386794558737357_7770900013873364992_n

Area of previous mining license for quartz and feldspar | Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

CATARINA ALVES SCARROTT (BORN IN COVAS, AND CURRENTLY A TEACHER IN LONDON, MEMBER OF UDCB)

I had known for a while that there was interest in lithium mining. I also knew there was a license. In the meantime, I had also read several research documents in which lithium reserves in Portugal were being promoted, specifically the ones here, in Covas de Barroso.

But the maps included in these documents weren’t very clear, nor was it clear what they were planning to do exactly and where these lithium reserves were. And besides that, the license then was for feldspar and quartz. So, things didn’t seem to add up. They stated that this project fell under the old license, but now they were talking about lithium, not feldspar and quartz. Mining feldspar and quartz involves cutting rocks and taking the them away. But lithium is an essential element, it needs to be refined through a very complex process.

I could see there was already an environmental impact study, but the area for the project seemed very far from the village. There was a map in one of the reports, and the map, however detailed, seemed to exclude the village. You couldn’t spot the village in it. But there were some landmarks on the map that led me to understand the extension of the project and its proximity to the village, and that made me very, very concerned.

But I think what worried me even more was how uninformed people here were, they had no idea what was going on. At the time, in 2017, the importance of lithium was not yet well understood. But by going through English newspapers and media, I knew it was already being a point of much discussion. Here in Portugal, that wasn’t the case. I think a lot of people here didn’t know what lithium was.

43627379_339503710133109_487045670708969472_n

Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

MARIANA RIQUITO (RESEARCHER, MEMBER OF UDCB)

I found out in early 2021, when we were organizing a protest against the far-right in Coimbra. Many people from all over the country came to that protest, we called for a large mobilization. It was then, during those conversations, that I learned about plans for lithium mining in Portugal.

And that same year, in May, Portugal held the presidency of the European Council and organized a “Green Mining” conference, to which it invited representatives of battery companies and lobbies, as well as the energy secretaries from all European Union member states, while communities were excluded from participating in the conference. So, a protest was organized there, in front of the CCB – Centro Cultural de Belém. And it was the first time I met people from the anti-mining movement in Covas do Barroso, as well as people involved in the same struggles in Montalegre, Serra da Arga and in other communities from northern Portugal.

That was also when I met some people who told me they had plans to organize a summer camp. I came to Covas for the first time in August 2021. And I fell in love with the village and the people, the beauty of the place. With how joyful this place is. With the way I was welcomed here.

I came back here several times in the following months. Anyway, I became quite attached. And when I started my PhD in February 2022, I asked my counsellors if I could reframe my research. Because I actually wanted to be more present and I wanted to be more involved here. And I ended up focusing my research on what is happening here in Covas.

49716191_394472027969610_5808412182248947712_n

Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

At the heart of this struggle lies the baldio – 2,000 hectares of community land democratically managed by a citizens’ assembly, where every voice counts, where rich and poor have the same rights.

AIDA FERNANDES

Much of the project will be implemented on the baldio, the communal land. Currently, the baldio comprises the entire forest surrounding the village of Covas, covering an area of about 2,000 hectares. Our communal land is being threatened, but above all, our community is being threatened. We are the community. Because there is no communal land without a community. No decision about this land can be made without the citizens meeting, without the consent of the people who live in Covas.

This land is also crucial in terms of the economy, it plays a central role. It’s where grazing happens, it’s where we collect firewood. It’s where we fish, since the river is included within the baldio. It’s where we hunt. Where we harvest mushrooms. These may seem like small things, but they are very important to the community, they carry a deep historical significance and are greatly appreciated by the villagers.

142596422_931841547565986_5357956590964470930_n

Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

It’s important for other reasons. In addition to being a source of income for the community, the management of the communal land has also allowed us to create jobs and generate employment opportunities in the community, in the village.

[UDCB member] Carlos Libo says something that makes perfect sense, which is: “The common land does not discriminate between the rich and the poor.” In other words, everyone has equal rights. This is very important. It is land to which we all have a right, and which for generations has been the livelihood of many families.

That’s why I think it makes perfect sense to continue to preserve and maintain this communal land. Because, in addition to being an economic asset, this land is also our heritage, it’s something we care for, we have a very strong connection to it.

142743164_931841577565983_3246430788822908945_n

Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

After years of failing to obtain permission from the community to enter the land, the company resorted to a devastating legal tool – administrative easement. What followed were months of repression and resistance.

AIDA FERNANDES

The mining company arrived here in 2017. By the end of 2018, we finally managed to clarify some of our rights. One of them was that they could only enter our land if they had our permission. We we were then able to halt the prospecting works at the end of 2018. Until December 2024 they were not allowed to enter the communal lands, nor the private lands nor the pieces of land owned by the parish council.

The company then resorted to this legal mechanism, called administrative easement, which was conceded by the government. And against everyone’s wishes, we learned from the national guard that this was going to go forward. And it was very intense, it was very tense, it was very painful for some people to see the machines on their land without their permission. The national guard threatened them and forced them to leave their land.

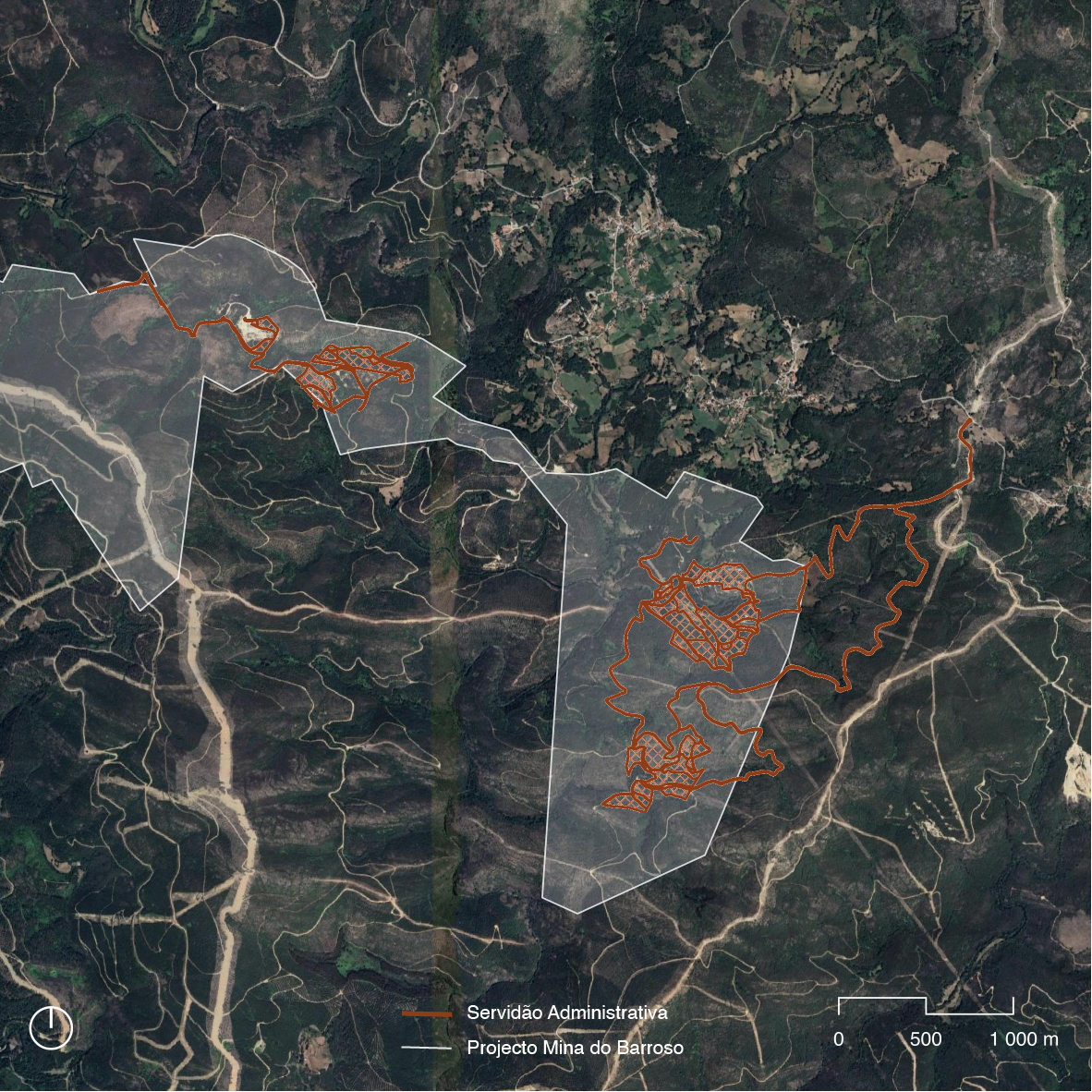

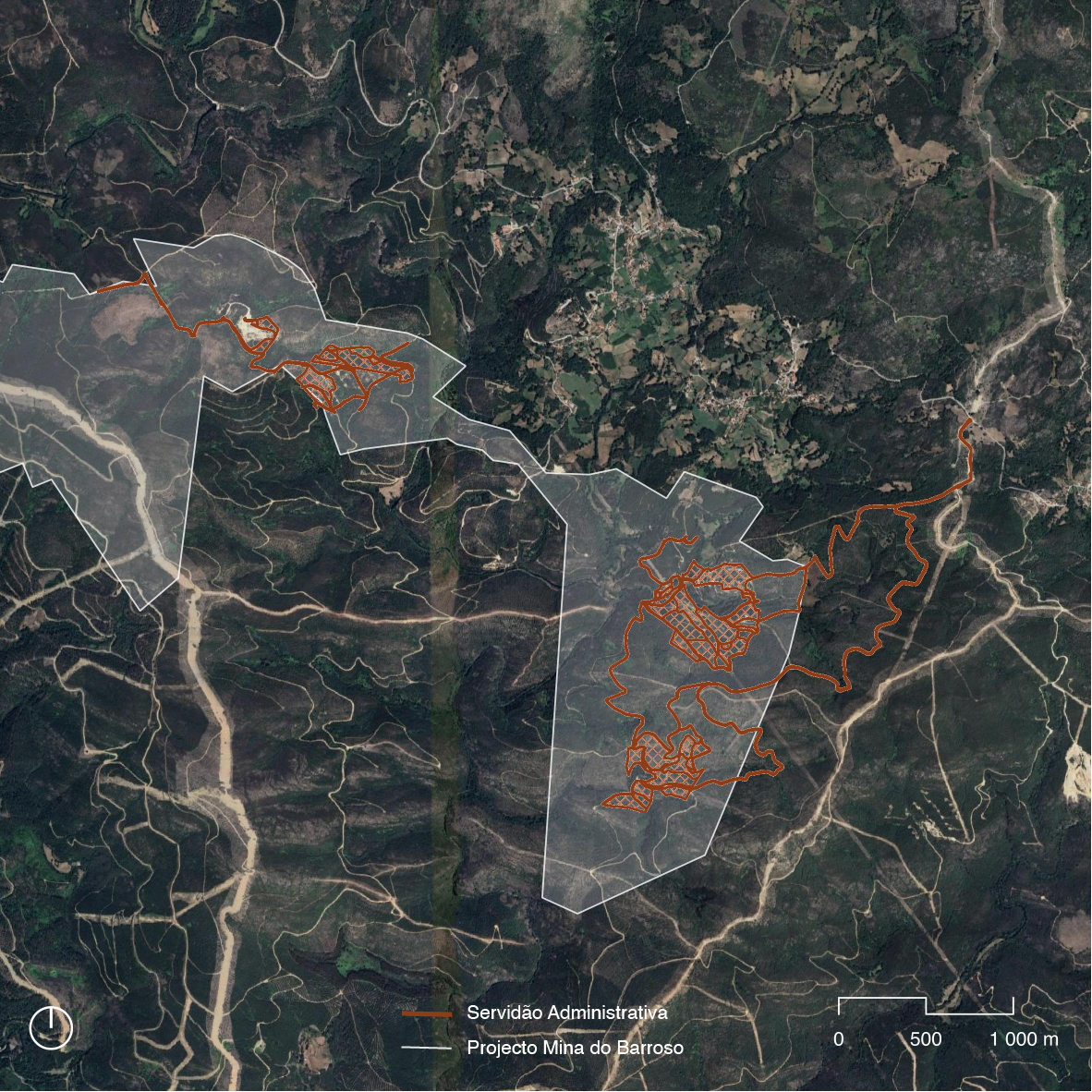

484646160_975374821400909_8831129697090075916_n

Mining project area (in white) and administrative easement area (in orange) | Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

Today is extremely hot out, and in the winter it was extremely cold. Maria, Benjamim, and Dinis were on their land. And Dinis called me and said, “They are telling us that if we don’t leave in 5 minutes, they’ll arrest us.” And they were there by themselves, so they had to give in.

There were other days where we left home thinking, “Today I’m going to jail.” Because we were there to defend the territory, and we called the media. And that day we were lucky, because when the national guard saw journalists there, they backed off.

They eventually managed to go ahead with the work they wanted to do, against the will of the population. They claim that they have a great relationship with the community, and that the project is doing great. But they can only enter the land by using this legal mechanism. They have now asked for a second easement, which we have already contested. Let’s see what happens next.

476388996_18178408216311923_8608923877927140887_n

The National Guard (GNR) enforcing the administrative easment | Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

CATARINA ALVES SCARROTT

The local population does not accept the project. And, based on that alone, the project should have never been officially classified as strategic. It also shouldn’t be classified as such, in our opinion, since this is not an acceptable project in terms of its environmental impact. It’s not enough that the environmental impact statement rests upon certain conditions. It should never have advanced to the next stage.

This classification process was not properly done. We do not know what information was used in the process. Whether or not the criteria that had been defined were respected. And therefore, the European Union will also be challenged by us. We have already requested an internal review regarding this classification. We will wait and see. And then, depending on the response we get, we may appeal to the European Court of Human Rights.

I think European policies need to be redefined. If we are talking about a crisis, “business as usual” won’t do. Things have to change. Consumption has to change. It’s a transition made for mining companies, made for the automotive industry. It is not made for the future of the planet, it is not made for us, it is not made for the future of communities.

46802653_368125580604255_6320235360374751232_n

The mining company was able to proceed, against the will of the local population | Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

Faced with powerful economic interests and divisive strategies, the community organized itself. Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso was born as a nonpartisan community grassroots organization, rooted in the values of solidarity and respect for nature that have always defined this community.

CATARINA ALVES SCARROTT

Starting the community organization was very, very important, because without it we would not have a united voice. It’s also crucial to emphasise that we are not linked to any political party. It was the community’s decision to unite against this project and to have a voice that is independent of political parties and other influences.

In fact, the organization would not be possible if it wasn’t rooted in the values that characterise this community. Solidarity, sustainability, respect for nature, respect for people.

Abril_DSC_8566

Local population during the 2025 resistance summer camp | Credit: Abril

AIDA FERNANDES

For us, this is all new, because we’ve never had a mine on our doorstep before. We’ve never dealt with such powerful economic interests. This is the first time we’ve ever challenged a government decision.

Right now, the project is supported by those who are making money from it, or by those who see the prospect of profitability. Among the rest of us, whenever the project is discussed, everyone thinks it’s not good for the community.

Fortunately, we’ve built a large network of friends across the globe, people who have experienced the impact of mining projects. And what they say is that the strategy is always the same. It is divide and rule.

Abril_DSC_8589

Local farmer and UDCB member Carlos Libo, during the 2025 resistance summer camp | Credit: Abril

But what is this rush for lithium for, anyway? The European Union says it needs 60 times more lithium by 2050. But is this the only possible solution to tackle the climate crisis?

CATARINA ALVES SCARROTT

When we found out that the project was going to happen here, the first thing we asked was: “Why us? Why are they going to sacrifice us?” And then, as we began to understand the project, the question became: “What for?”

There’s a local saying, that those who don’t save land and firewood, are spending something that isn’t their own. Exploitation makes no sense. It’s just “business as usual”. Everything remains as it is. We continue consuming in the same ways. And that goes against the values that the community defends.

Abril_DSC_8525

The Covas river | Credit: Abril

MARIANA RIQUITO

And when we look at the estimates for lithium demand, they actually refer to the needs of industries such as the automotive industry, the mining industry, or the arms industry.

This means that when the European Union claims that, “we need 60 times more lithium by 2050,” and that this is of the utmost urgency, it is actually saying that we need to replace our current car fleet with electric cars.

If the equation was: “OK, let’s invest in railways and public transport. Let’s reduce armaments. Let’s reduce industries such as fast fashion. Let’s end planned obsolescence. Let’s build things that are made to last. Let’s recycle the materials and minerals we already have.” If this was the beginning of the equation, it’s obvious the need for lithium would be drastically reduced, and there are also many studies on this very subject.

And maybe we can redefine our needs and redefine our priorities. Maybe those could be: “OK. From now until 2050, and forever afterwards, let’s keep our rivers clean, our forests alive, and our communities thriving.” And if that’s the priority, and if that’s the need, then the beginning of the equation will be completely different.

Abril_DSC_8550

Forest surrounding the village of Covas do Barroso | Credit: Abril

And I think it’s undoubtedly very important to make a transition. I don’t like to say it’s a transition. I think it’s a transformation, and it goes far, far beyond just changing the energy source or changing an energy storage component. It really has to be a holistic and integrated transformation of the way we move. What we eat, where does it come from? What we wear, where does it come from? How do we relate to each other?

And I think that in places like Covas, we can learn from these communities about other ways of relating to our surroundings, beyond this endless march of extracting more to produce more, so we can have new cars, new cell phones, new clothes, new… Always more, more, more, more, more.

142943922_931841660899308_4207421576055721755_n

Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

The battle of Covas do Barroso is not an isolated one. It is about the model of development we want, about the future we imagine. How can we support this and other similar struggles? How can we say no to the mine, yes to life?

MARIANA RIQUITO

I think there are several things that can be done, even for those who are not in Covas. For those in Portugal, I obviously think it is important to support this movement and to bring it to the cities by organizing conversations, lectures, fundraisers, or making donations to local communities and associations.

Because this is clearly not an isolated issue. Studies have shown that if the project goes forward, which it won’t, it would lead to a catastrophic failure of the tailings dam, and the tailings would flow into the Douro river and, therefore, into the Atlantic Ocean. In other words, it would affect the entire river basin here in northern Portugal. For that reason alone, this can’t be seen as an isolated problem for Covas. But it’s also not a problem just for Covas because opening mines here would then mean opening mines in many other places and would set a terrible precedent.

Abril_DSC_8577

Protest during the 2025 resistance summer camp | Credit: Abril

And then, another thing that is crucial is consistently fighting the political narrative that they want to sell us, according to which the world has to be this way, and the transition has to be this way. Because it doesn’t have to be this way. And there are many other ways of being and there are many other ways of living. And we don’t have to repeat the exact same mistakes, the same consumption, production, and living patterns.

And so it is important to show that it can be different. Saying “No to the mine” is also about that. It is also about showing that things can be different. The future does not have to be about more mining everywhere. The future can be one where communities live off their forest, connected with their rivers, with their neighbors, with their families.

For those around the world, the same strategies apply. You can also help bring visibility to this this struggle, and you can support it. Even from afar, you can contribute through donations, but also by fighting these narratives.

Abril_DSC_8614

Protest during the 2025 resistance summer camp | Credit: Abril

AIDA FERNANDES

I think Mariana has covered pretty much everything. But above all, we also need people to come to Covas, if they can. Even if it’s just for a hug, because some days that’s what we need the most.

CATARINA ALVES SCARROTT

It’s David versus Goliath. We are “ordinary people in an extraordinary situation.” We are fighting against professionals, against financial speculation, against mining companies. We are not professionals. We are regular people with regular jobs who knew nothing about mines, and who are learning, little by little. And we face all these hardships, we face propaganda.

And it can be very difficult for us to get the message out there. And it is very difficult for us to show the reality on the ground. Because we are here, but we are few, and we are fighting against all these things.

And so it is very important that other people come here to see for themselves, and to help us get the message out there about what is happening. And help us fight this narrative and this incursion, this intrusion, this repression that we suffer here. Because it deeply affects us.

SAY NO TO THE MINE, YES TO LIFE. SUPPORT UNIDOS EM DEFESA DE COVAS DO BARROSO:

External Link

External Link

Azimuth World Foundation does not engage in fundraising for itself or its partners, nor do we collect donations. The links we are sharing above will take you directly to UDCB’s and ACBP’s official websites.

Connecting the Dots with Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

CtD_UDCB_PostCover.001

Village of Covas do Barroso, northern Portugal

Fighting against a large-scale lithium mining project, a community in northern Portugal defends its sustainable farming practices and the World Agricultural Heritage Site they’ve called home for generations

For this episode of Connecting the Dots, we bring you a conversation recorded in Covas do Barroso, in northern Portugal, during the annual resistance camp against lithium mining.

This small mountain village, recognized by the FAO as a World Agricultural Heritage Site, faces plans for one of Europe’s largest open-pit lithium mines. A mine that threatens to destroy 2,000 hectares of community land, contaminate the waters of the Covas River—a tributary of the Douro river—and displace a community that has lived self-sufficiently for generations.

We hear from Aida Fernandes (local farmer), Catarina Alves Scarrott (born in Covas, and currently a teacher in London) and Mariana Riquito (researcher), all members of the local, grassroots association Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso (UDCB).

Follow UDCB’s work at their official website, or through their official Instagram and Facebook accounts.

If you’re in the United States, you can find ways to support this cause and to get involved at savebarroso.com – the official website of Americans for the Conservation of Barroso Portugal, a US-based 501(c)(3) organization.

Play the video version below (English subtitles available), or scroll down for the podcast version (dubbed in English) and for the transcript (in English).

CONNECTING THE DOTS – PODCAST

Are you a podcast fan? Make sure you subscribe to the podcast version of our Connecting the Dots series here.

ENGLISH TRANSCRIPT (TRANSLATION)

43662679_339503800133100_4064701076920598528_n

Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

AIDA FERNANDES (LOCAL FARMER, MEMBER OF UDCB)

Covas do Barroso is a predominantly agricultural village. People make their living from farming and sheep husbandry. I myself am a farmer, I own cows, and I make my living from farming.

And Covas do Barroso is a unique place. Because it has characteristics that make us basically self-sufficient. We are able to produce everything we need for our day-to-day lives, from olive oil to vegetables, meat, fruit, and fish from our river.

So I think this is a great asset, and it’s a privilege to be able to live like this, in a place where we have fresh air, clean water, and lots of greenery.

120540483_846408832775925_706895992404984681_n

Aida Fernandes | Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

In May 2017, suspicious movements began on the surrounding area. An old 2006 license for quartz and feldspar mining was being used for something very different—and much bigger.

AIDA FERNANDES

There had been a quartz and feldspar quarry since 2006, which had never been used. In May 2017, there was some activity taking place in the area. I remember asking one of the workers what they were doing. She said, “Oh, just some work.” Summer is a busy time for us here. We are like ants, gathering in the summer, so we have enough for the winter. People are focused on their tasks and don’t pay much attention to anything else.

A month later, Catarina called me from London to ask me what was going on in Covas. When she called me, I just replied, “Nothing’s going on. It’s very hot and we’re very busy.” And she said, “But I’m reading here that the largest open-pit mine will be installed in Covas do Barroso.”

I didn’t even know what lithium was, I admit. And then when she began describing what this process involved, that unlike the quarry that was there now, the new project would also include a washing plant, and when she described how big it would be, it was a shock, it was scary. “That’s impossible, that can’t be true. No way. How can they plan something like this without even informing us?”

49564077_386794558737357_7770900013873364992_n

Area of previous mining license for quartz and feldspar | Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

CATARINA ALVES SCARROTT (BORN IN COVAS, AND CURRENTLY A TEACHER IN LONDON, MEMBER OF UDCB)

I had known for a while that there was interest in lithium mining. I also knew there was a license. In the meantime, I had also read several research documents in which lithium reserves in Portugal were being promoted, specifically the ones here, in Covas de Barroso.

But the maps included in these documents weren’t very clear, nor was it clear what they were planning to do exactly and where these lithium reserves were. And besides that, the license then was for feldspar and quartz. So, things didn’t seem to add up. They stated that this project fell under the old license, but now they were talking about lithium, not feldspar and quartz. Mining feldspar and quartz involves cutting rocks and taking the them away. But lithium is an essential element, it needs to be refined through a very complex process.

I could see there was already an environmental impact study, but the area for the project seemed very far from the village. There was a map in one of the reports, and the map, however detailed, seemed to exclude the village. You couldn’t spot the village in it. But there were some landmarks on the map that led me to understand the extension of the project and its proximity to the village, and that made me very, very concerned.

But I think what worried me even more was how uninformed people here were, they had no idea what was going on. At the time, in 2017, the importance of lithium was not yet well understood. But by going through English newspapers and media, I knew it was already being a point of much discussion. Here in Portugal, that wasn’t the case. I think a lot of people here didn’t know what lithium was.

43627379_339503710133109_487045670708969472_n

Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

MARIANA RIQUITO (RESEARCHER, MEMBER OF UDCB)

I found out in early 2021, when we were organizing a protest against the far-right in Coimbra. Many people from all over the country came to that protest, we called for a large mobilization. It was then, during those conversations, that I learned about plans for lithium mining in Portugal.

And that same year, in May, Portugal held the presidency of the European Council and organized a “Green Mining” conference, to which it invited representatives of battery companies and lobbies, as well as the energy secretaries from all European Union member states, while communities were excluded from participating in the conference. So, a protest was organized there, in front of the CCB – Centro Cultural de Belém. And it was the first time I met people from the anti-mining movement in Covas do Barroso, as well as people involved in the same struggles in Montalegre, Serra da Arga and in other communities from northern Portugal.

That was also when I met some people who told me they had plans to organize a summer camp. I came to Covas for the first time in August 2021. And I fell in love with the village and the people, the beauty of the place. With how joyful this place is. With the way I was welcomed here.

I came back here several times in the following months. Anyway, I became quite attached. And when I started my PhD in February 2022, I asked my counsellors if I could reframe my research. Because I actually wanted to be more present and I wanted to be more involved here. And I ended up focusing my research on what is happening here in Covas.

49716191_394472027969610_5808412182248947712_n

Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

At the heart of this struggle lies the baldio – 2,000 hectares of community land democratically managed by a citizens’ assembly, where every voice counts, where rich and poor have the same rights.

AIDA FERNANDES

Much of the project will be implemented on the baldio, the communal land. Currently, the baldio comprises the entire forest surrounding the village of Covas, covering an area of about 2,000 hectares. Our communal land is being threatened, but above all, our community is being threatened. We are the community. Because there is no communal land without a community. No decision about this land can be made without the citizens meeting, without the consent of the people who live in Covas.

This land is also crucial in terms of the economy, it plays a central role. It’s where grazing happens, it’s where we collect firewood. It’s where we fish, since the river is included within the baldio. It’s where we hunt. Where we harvest mushrooms. These may seem like small things, but they are very important to the community, they carry a deep historical significance and are greatly appreciated by the villagers.

142596422_931841547565986_5357956590964470930_n

Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

It’s important for other reasons. In addition to being a source of income for the community, the management of the communal land has also allowed us to create jobs and generate employment opportunities in the community, in the village.

[UDCB member] Carlos Libo says something that makes perfect sense, which is: “The common land does not discriminate between the rich and the poor.” In other words, everyone has equal rights. This is very important. It is land to which we all have a right, and which for generations has been the livelihood of many families.

That’s why I think it makes perfect sense to continue to preserve and maintain this communal land. Because, in addition to being an economic asset, this land is also our heritage, it’s something we care for, we have a very strong connection to it.

142743164_931841577565983_3246430788822908945_n

Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

After years of failing to obtain permission from the community to enter the land, the company resorted to a devastating legal tool – administrative easement. What followed were months of repression and resistance.

AIDA FERNANDES

The mining company arrived here in 2017. By the end of 2018, we finally managed to clarify some of our rights. One of them was that they could only enter our land if they had our permission. We we were then able to halt the prospecting works at the end of 2018. Until December 2024 they were not allowed to enter the communal lands, nor the private lands nor the pieces of land owned by the parish council.

The company then resorted to this legal mechanism, called administrative easement, which was conceded by the government. And against everyone’s wishes, we learned from the national guard that this was going to go forward. And it was very intense, it was very tense, it was very painful for some people to see the machines on their land without their permission. The national guard threatened them and forced them to leave their land.

484646160_975374821400909_8831129697090075916_n

Mining project area (in white) and administrative easement area (in orange) | Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

Today is extremely hot out, and in the winter it was extremely cold. Maria, Benjamim, and Dinis were on their land. And Dinis called me and said, “They are telling us that if we don’t leave in 5 minutes, they’ll arrest us.” And they were there by themselves, so they had to give in.

There were other days where we left home thinking, “Today I’m going to jail.” Because we were there to defend the territory, and we called the media. And that day we were lucky, because when the national guard saw journalists there, they backed off.

They eventually managed to go ahead with the work they wanted to do, against the will of the population. They claim that they have a great relationship with the community, and that the project is doing great. But they can only enter the land by using this legal mechanism. They have now asked for a second easement, which we have already contested. Let’s see what happens next.

476388996_18178408216311923_8608923877927140887_n

The National Guard (GNR) enforcing the administrative easment | Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

CATARINA ALVES SCARROTT

The local population does not accept the project. And, based on that alone, the project should have never been officially classified as strategic. It also shouldn’t be classified as such, in our opinion, since this is not an acceptable project in terms of its environmental impact. It’s not enough that the environmental impact statement rests upon certain conditions. It should never have advanced to the next stage.

This classification process was not properly done. We do not know what information was used in the process. Whether or not the criteria that had been defined were respected. And therefore, the European Union will also be challenged by us. We have already requested an internal review regarding this classification. We will wait and see. And then, depending on the response we get, we may appeal to the European Court of Human Rights.

I think European policies need to be redefined. If we are talking about a crisis, “business as usual” won’t do. Things have to change. Consumption has to change. It’s a transition made for mining companies, made for the automotive industry. It is not made for the future of the planet, it is not made for us, it is not made for the future of communities.

46802653_368125580604255_6320235360374751232_n

The mining company was able to proceed, against the will of the local population | Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

Faced with powerful economic interests and divisive strategies, the community organized itself. Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso was born as a nonpartisan community grassroots organization, rooted in the values of solidarity and respect for nature that have always defined this community.

CATARINA ALVES SCARROTT

Starting the community organization was very, very important, because without it we would not have a united voice. It’s also crucial to emphasise that we are not linked to any political party. It was the community’s decision to unite against this project and to have a voice that is independent of political parties and other influences.

In fact, the organization would not be possible if it wasn’t rooted in the values that characterise this community. Solidarity, sustainability, respect for nature, respect for people.

Abril_DSC_8566

Local population during the 2025 resistance summer camp | Credit: Abril

AIDA FERNANDES

For us, this is all new, because we’ve never had a mine on our doorstep before. We’ve never dealt with such powerful economic interests. This is the first time we’ve ever challenged a government decision.

Right now, the project is supported by those who are making money from it, or by those who see the prospect of profitability. Among the rest of us, whenever the project is discussed, everyone thinks it’s not good for the community.

Fortunately, we’ve built a large network of friends across the globe, people who have experienced the impact of mining projects. And what they say is that the strategy is always the same. It is divide and rule.

Abril_DSC_8589

Local farmer and UDCB member Carlos Libo, during the 2025 resistance summer camp | Credit: Abril

But what is this rush for lithium for, anyway? The European Union says it needs 60 times more lithium by 2050. But is this the only possible solution to tackle the climate crisis?

CATARINA ALVES SCARROTT

When we found out that the project was going to happen here, the first thing we asked was: “Why us? Why are they going to sacrifice us?” And then, as we began to understand the project, the question became: “What for?”

There’s a local saying, that those who don’t save land and firewood, are spending something that isn’t their own. Exploitation makes no sense. It’s just “business as usual”. Everything remains as it is. We continue consuming in the same ways. And that goes against the values that the community defends.

Abril_DSC_8525

The Covas river | Credit: Abril

MARIANA RIQUITO

And when we look at the estimates for lithium demand, they actually refer to the needs of industries such as the automotive industry, the mining industry, or the arms industry.

This means that when the European Union claims that, “we need 60 times more lithium by 2050,” and that this is of the utmost urgency, it is actually saying that we need to replace our current car fleet with electric cars.

If the equation was: “OK, let’s invest in railways and public transport. Let’s reduce armaments. Let’s reduce industries such as fast fashion. Let’s end planned obsolescence. Let’s build things that are made to last. Let’s recycle the materials and minerals we already have.” If this was the beginning of the equation, it’s obvious the need for lithium would be drastically reduced, and there are also many studies on this very subject.

And maybe we can redefine our needs and redefine our priorities. Maybe those could be: “OK. From now until 2050, and forever afterwards, let’s keep our rivers clean, our forests alive, and our communities thriving.” And if that’s the priority, and if that’s the need, then the beginning of the equation will be completely different.

Abril_DSC_8550

Forest surrounding the village of Covas do Barroso | Credit: Abril

And I think it’s undoubtedly very important to make a transition. I don’t like to say it’s a transition. I think it’s a transformation, and it goes far, far beyond just changing the energy source or changing an energy storage component. It really has to be a holistic and integrated transformation of the way we move. What we eat, where does it come from? What we wear, where does it come from? How do we relate to each other?

And I think that in places like Covas, we can learn from these communities about other ways of relating to our surroundings, beyond this endless march of extracting more to produce more, so we can have new cars, new cell phones, new clothes, new… Always more, more, more, more, more.

142943922_931841660899308_4207421576055721755_n

Credit: Unidos em Defesa de Covas do Barroso

The battle of Covas do Barroso is not an isolated one. It is about the model of development we want, about the future we imagine. How can we support this and other similar struggles? How can we say no to the mine, yes to life?

MARIANA RIQUITO

I think there are several things that can be done, even for those who are not in Covas. For those in Portugal, I obviously think it is important to support this movement and to bring it to the cities by organizing conversations, lectures, fundraisers, or making donations to local communities and associations.

Because this is clearly not an isolated issue. Studies have shown that if the project goes forward, which it won’t, it would lead to a catastrophic failure of the tailings dam, and the tailings would flow into the Douro river and, therefore, into the Atlantic Ocean. In other words, it would affect the entire river basin here in northern Portugal. For that reason alone, this can’t be seen as an isolated problem for Covas. But it’s also not a problem just for Covas because opening mines here would then mean opening mines in many other places and would set a terrible precedent.

Abril_DSC_8577

Protest during the 2025 resistance summer camp | Credit: Abril

And then, another thing that is crucial is consistently fighting the political narrative that they want to sell us, according to which the world has to be this way, and the transition has to be this way. Because it doesn’t have to be this way. And there are many other ways of being and there are many other ways of living. And we don’t have to repeat the exact same mistakes, the same consumption, production, and living patterns.

And so it is important to show that it can be different. Saying “No to the mine” is also about that. It is also about showing that things can be different. The future does not have to be about more mining everywhere. The future can be one where communities live off their forest, connected with their rivers, with their neighbors, with their families.

For those around the world, the same strategies apply. You can also help bring visibility to this this struggle, and you can support it. Even from afar, you can contribute through donations, but also by fighting these narratives.

Abril_DSC_8614

Protest during the 2025 resistance summer camp | Credit: Abril

AIDA FERNANDES

I think Mariana has covered pretty much everything. But above all, we also need people to come to Covas, if they can. Even if it’s just for a hug, because some days that’s what we need the most.

CATARINA ALVES SCARROTT

It’s David versus Goliath. We are “ordinary people in an extraordinary situation.” We are fighting against professionals, against financial speculation, against mining companies. We are not professionals. We are regular people with regular jobs who knew nothing about mines, and who are learning, little by little. And we face all these hardships, we face propaganda.

And it can be very difficult for us to get the message out there. And it is very difficult for us to show the reality on the ground. Because we are here, but we are few, and we are fighting against all these things.

And so it is very important that other people come here to see for themselves, and to help us get the message out there about what is happening. And help us fight this narrative and this incursion, this intrusion, this repression that we suffer here. Because it deeply affects us.

SAY NO TO THE MINE, YES TO LIFE. SUPPORT UNIDOS EM DEFESA DE COVAS DO BARROSO:

External Link

External Link

Azimuth World Foundation does not engage in fundraising for itself or its partners, nor do we collect donations. The links we are sharing above will take you directly to UDCB’s and ACBP’s official websites.